- Understanding parts of the dog and how they relate to good grooming

- Exploring how diet and good care can affect your dog’s health

- Discovering how haircoat, genetics, and other factors may affect your dog’s grooming

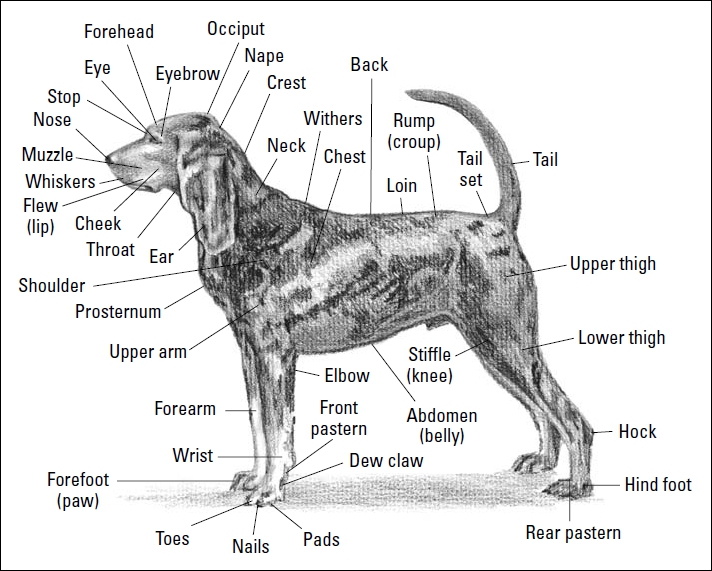

Anatomy of the Dog: The Hipbone’s Connected to the . . .

Head

– Dolichocephalic: This head type is the long and thin head seen in dog breeds like the Collie, Borzoi, and Saluki. Dogs with this type of head have really long muzzles and noses and usually have really good eyesight or a keen sense of smell.

– Brachycephalic: This head type is the exact opposite of dolichocephalic heads. Brachycephalic heads are short with muzzles that often have a pushed-in look. Some dog breeds with this type of head have problems breathing because of the closeness of their features, and some have wrinkles that must be cleaned frequently. Dogs with brachycephalic heads include the Bulldog, Pug, and Pekingese.

– Mesaticephalic: This head type is medium-sized, as seen in the Samoyed, Brittanies, and Alaskan Malamutes. These dogs need general grooming for their heads.

Remember

Depending on the type of head your dog has, you may have certain grooming issues. For example, dogs with brachycephalic heads may have eyes that bulge, and extreme care must be taken to avoid scratching them. Long noses of the dolichocephalic head type may be prone to getting things like grass awns (bristle-like tips) in them more easily, because, well, the dog’s nose naturally arrives five minutes before the rest of the dog.

– Nose: You’re all familiar with your dog’s nose. For one thing, dog noses are often cold and wet, and of course, they usually get stuck where they’re not wanted. Plenty of terms associated with the dog’s nose refer either to its shape (Ram’s nose or Roman nose) or color (liver, snow nose, or Dudley nose).

– Muzzle (foreface): The muzzle or foreface is the part of the skull that’s comprised of the upper and lower jaws. You’ll pay close attention to the dog’s muzzle while grooming.

Muzzle also is a term for a device that keeps the dog’s jaws shut and thus inhibits biting.

– Stop: The stop is an indentation (sometimes nonexistent) between the muzzle and the braincase or forehead (see next item).

– Forehead (braincase): The forehead is the portion of the head that’s similar to your own forehead; it goes from the back point of the skull (occiput) to the stop and eyebrows.

– Occiput (point of skull): The occiput is simply the highest point of the skull at the back of the head and a prominent feature on some dogs.

– Ears: It’s pretty obvious what these are, but different dogs have different types of ear carriage. Among the several types are

- Pricked: Pricked ears are upright.

- Dropped: Dropped ears hang down. Dogs with this kind of ears need more care for their ears because they’re more prone to getting infections than dogs with pricked ears.

- Button: Button ears have a fold in them. Button ears, like dropped ears, may need more care because they’re more prone to getting infections than pricked ears.

- Cropped: Cropped ears are surgically altered.

You need to clean your dog’s ears and check for problems like ear mites. You likewise want to check frequently behind the ears for knots and tangles that form.

– Eyes: Again, the eyes are a pretty obvious part of the anatomy, but a multitude of descriptions deal with a dog’s eye color and shape. Most are self-explanatory. You may be cleaning tear stains beneath the eyes if you have a breed that’s prone to that condition.

– Eyebrows: Like humans, dogs have eyebrows, or simply brows.

– Whiskers: Dogs have whiskers that provide some sensory feeling. They sometimes are trimmed to provide a clean look for the muzzle.

– Flews (lips): Flews is just a fancy word for a dog’s lips. You’ll be touching them a lot when you brush your dog’s teeth.

– Cheek: The skin along the sides of the muzzle is what cheeks are to a dog. Dog cheeks are in a position similar to where your own cheeks are.

Neck and shoulders

The neck and shoulders are the next parts of the canine anatomy that I cover. Parts of the neck and shoulders include the

– Nape: The nape of the neck is where the neck joins the base of the skull in the back of the head. If you’re clipping around the neck, you’ll quite often need to locate the nape.

– Throat: Like your own throat, the dog’s throat is beneath the jaws. It’s tender, and many dogs don’t like their throats handled roughly. Be mindful when brushing or clipping.

– Crest: The crest starts at the nape and ends at the withers (see the last item in this list).

– Neck: The neck is pretty self-explanatory; in dogs, it runs from the head to the shoulders.

– Shoulder: The shoulder is the top section of the foreleg from the withers to the elbow.

– Withers: One of those horse terms I mentioned earlier in the “Anatomy of the Dog: The Hipbone’s Connected to the . . .” section, the withers are the top point of the shoulders, making them the highest point along the dog’s back.

Back and chest

– Prosternum: The prosternum is the top of the sternum, a bone that ties the rib cage together.

– Chest: The chest is the entire rib cage of the dog.

– Back: The back runs from the withers to the loins, or from the point of the shoulders to the end of the rib cage. The term back is sometimes used to describe the back and the loin.

– Flank: The flank refers to the side portion of the dog between the end of the chest and the rear leg.

– Abdomen (belly): The belly portion of the dog is notably the underside of the dog from the end of its rib cage to its tail. If your dog’s belly is low to the ground, you probably have to take a little extra care in making sure it stays clean.

– Loin: The loin is the portion of the back between the end of the rib cage and the beginning of the pelvic bone.

Forelegs and hind legs

– Upper arm: The upper arm on the foreleg is right below the shoulder and is comprised of the humerus bone, which is similar (in name anyway) to the one found in your own upper arm. It ends at the elbow.

– Elbow: The elbow is the first joint in the dog’s leg that’s located just below the chest on the back of the foreleg. It’s like your elbow.

– Forearm: The long bone that runs after the elbow on the foreleg is the forearm. Like your arms, it’s comprised of the ulna and radius. The forearm may have feathering on the back of the arm that tends to pick up burrs and other foreign objects; it can also mat and tangle.

– Wrist: The wrist is the lower joint below the elbow on the foreleg. This joint bears as much as 90 percent of the dog’s weight when he’s jumping or doing other athletic feats.

– Pastern (front and rear): Sometimes called the carpals, pasterns are equivalent to the bones in your hands and feet — not counting fingers and toes. Like the wrists, pasterns are weight-bearing bones (especially the front ones) that are subject to many of the injuries suffered by sports dogs.

– Foot or paw (forefoot or hind foot): Try just standing on your toes or fingers, and you get an idea of what dogs do their entire lives. The foot or paw has nails (sometimes called claws), paw pads, and usually dewclaws. Most dogs have larger forefeet than hind feet. Among the many descriptions for the shape of the dog’s foot are

- Splayed: A dog with splayed feet has toes that are in a splayed or wide position when the dog steps down.

- Hare: Hare feet have middle two toes jutting out farther than the outer two toes, making the dog’s foot look like a rabbit’s foot.

- Snowshoe: Snowshoe feet are round and compact with heavy webbing between the toes and plenty of fur. Snowshoe feet are often seen in northern breeds like Samoyeds and Siberian Huskies.

– Toes: The toes of a dog are the equivalent of fingers and toes of your hands and feet. Although a dog’s toes don’t wiggle too much, dogs can move them in a stretch motion or even curl them up. You occasionally have to trim the hair between the pads of the toes.

– Dewclaws: Dewclaws are vestiges of thumbs on your dog. Because dogs never figured out the opposable thumbs concept (thank goodness, too — can you imagine what mischief they’d get into with them?), their thumbs, if you will, have become more or less useless appendages. Some dogs are not even born with them, and many are born with only front dewclaws. Some breeders elect to remove dewclaws when their puppies are a few days old, but some standards require intact dewclaws or even double dewclaws (two dewclaws on each foot — as if you had two thumbs). Dewclaws, like the other toenails, grow. Some dog owners swear they grow faster than the other nails. Because they get no wear from walking, they need to be clipped to prevent them from growing into the pad or breaking off.

– Nails: The toenails or claws on the end of each toe are actually incorporated with part of the last bone of the toes. You need to clip toenails about once a week.

– Pads: On the underside of the foot are several pads, including one main pad (communal pad) and a pad under each toe, for a total of five pads. If you look at the back of the foreleg, you can find stopper pads behind the wrist. Six pads are found on the forelegs and five on the back — unless your dog has more than one dewclaw per front leg, and then there may be pads associated with them.

– Upper thigh: The part of the dog’s leg situated above the knee, or stifle, on the hind leg is the upper thigh. It corresponds to that portion of the leg where the femur is in humans.

– Stifle (knee): The stifle is the joint that corresponds to the knee in humans. It sits on the front of the hind leg in line with abdomen.

– Lower thigh: The lower thigh is the portion of hind leg situated beneath the stifle (knee); it extends to the hock joint (see next bullet). It runs along the fibula and tibia bones in the dog’s leg. Some dogs have feathering along the back of their lower thighs and hocks, so it’s important to make sure the feathering is groomed properly and kept free of mats.

– Hock: This oddly shaped joint makes a sharp angle at the back of the dog’s legs. It corresponds with your ankle.

Rear and tail

– Rump (or croup): This part of the dog is the proverbial rear end; it’s where the pelvis bone is. You need to use care in grooming this section because it’s tender. Fluffy hairs often found behind the rump under the tail tend to attract plenty of knots, tangles, and other nasties.

– Tail set: The tail set is where the tail attaches to the rump. Some dogs have high tail sets, others have low ones.

– Tail: Everyone recognizes the dog’s tail (or its absence). It’s usually wagging at you. The tail is a great place for picking up burrs, prickly stuff, mats, and tangles, especially if the tail fur is long. Special care is needed to keep the tail looking great.

Considering Factors That Influence a Dog’s Appearance

Genetics

Tip

If you’re planning to buy a new dog in the future, you need to look for a reputable breeder (check out the nearby “Looking for a reputable breeder” sidebar) who does health screening and testing. Although screening can’t guarantee a 100 percent healthy dog, it does reduce your risk of buying a sick dog. Dogs from reputable breeders generally cost no more than those from disreputable sources — so buyer beware.

Looking for a reputable breeder | |

If you’ve ever bought a dog who ended up with a hereditary disease, you’re probably wondering whether you can do anything to minimize the risk of buying a sick dog. Actually, you can do just that by purchasing your dog from a reputable breeder. Unlike backyard breeders — people who breed dogs for the money, because they think it’s fun, or because they want another dog just like Fluffy — or puppy mills that breed dogs solely for profit and not for health or quality, reputable breeders try to improve the breed and want to breed healthy dogs. Instead of breeding multiple litters every year, they settle for just one or two litters. Puppies aren’t always available, and reputable breeders usually have waiting lists for their puppies. You can discover more about finding a reputable breeder in my book, Bring Me Home: Dogs Make Great Pets (Howell Book House, 2005), but here’s a basic rundown of what reputable breeders do. They

|

Puppies aren’t always available from reputable breeders; you can nevertheless begin your search for the right dog at the AKC’s Web site at www.akc.org. |

– Allergies: Allergies often manifest themselves in a poor-looking coat.

– Addison’s disease: This disease is caused by a lack of or deficiency in hormones produced by the pituitary or adrenal glands and can result in hair and skin problems.

– Cushing’s disease: This disease is the opposite of Addison’s in that it’s an overproduction of hormones; it causes hair loss and poor skin.

– Hyperthyroidism: This condition is an overabundance of the thyroid hormone. Although rare in dogs, it’s usually associated with cancer.

– Hypothyroidism: This condition is a lack of thyroid hormone in dogs. It causes brittle coats and hair loss.

– Sebaceous adenitis: This hereditary skin condition is a disease that destroys the oil-producing sebaceous glands and causes hair loss.

– Autoimmune disorders: These disorders are varied and can cause hair loss and scaly skin.

– Zinc-responsive dermatosis: This condition, which may be hereditary, is one in which the dog fails to absorb enough zinc from his diet. Scaly skin and hair loss result.

– Coat funk: This condition is at least congenital if not hereditary. The outer coat breaks off, leaving the woolly undercoat exposed.

Haircoat

- How well you feed your dog

- How well you take care of your dog

- How often you take care of the haircoat

These three factors are crucial to how your dog looks after being groomed.

Health

Remember

Your dog’s appearance is a good indication of what’s going on inside. If the coat looks dry and icky or oily or if the hair is thinning, that may be a sign that something more serious is wrong with your dog. When that’s the case, your dog needs to be examined by a veterinarian so the problem can be diagnosed and fixed. Your dog will thank you.

Exercise

Starting an exercise regimen | |

So you’ve decided you have a pudgy pooch. Before you strap on your Nikes for a ten-mile run with Fido, stop and think. If you’re in shape, you didn’t get into shape by running a marathon right off the bat . . . so don’t expect your dog to do it. Overstressing your dog can be just as hazardous as overstressing an obese person. Be sensible; start out easy, but definitely start. Here are some pointers for beginning an exercise regimen with your dog:

|

|

Diet

Remember

One of the first places good or bad diets show up in is your dog’s haircoat. If he has a dull, brittle, sparse, greasy, or dry coat that’s shedding excessively, he may have a lousy diet. (These conditions show up for other reasons too, but feeding him a lousy diet can’t help.) But if you feed your dog a healthy and nutritious diet (see the next section), he’s bound to look and feel better. Abrupt changes in the haircoat call for investigation and consultation with your veterinarian.

Exploring the Importance of Nutrition

Providing a balanced diet

Remember

Regardless of whether you’re getting your dog food from the supermarket, buying specialty pet food, or preparing a home-cooked or raw diet for your dog, you should always adhere to the AAFCO standards.

Warning!

Feeding a diet that isn’t balanced and strays too far from the guidelines can seriously ruin your dog’s health. For example, too much or too little calcium can cause bone problems (thinning in the latter case) and can lead to deadly fractures. Overfeeding certain vitamins can actually cause deadly heart problems. Messing around with nutrition isn’t usually a good idea, so unless you know what you’re doing when it comes to formulating a dog’s diet, steer clear of homemade and raw diets until you’ve at least talked to a veterinary nutritionist about how to formulate a balanced diet for your dog.

Tip

Changing your dog’s foodWhenever you change your dog’s food, you need to do it gradually to avoid stomach upsets. Start with 10 percent of the new food and 90 percent of the old food on the first day. Each subsequent day, increase the new food by 10 percent and decrease the old food by 10 percent. After your dog is weaned onto the new dog food, don’t expect to see any changes in your dog’s appearance for at least six to eight weeks. This amount of time is the shortest in which research has shown verifiable physical changes in dogs. |

Feeding for a beautiful coat

Warning!

Not all commercial dog foods are formulated to meet AAFCO guidelines. Always look on the dog food package for a statement of nutritional adequacy that the dog food meets or exceeds AAFCO guidelines.

Remember

Most dog owners overfeed their dogs, and as a result, obesity is as serious a problem among pets as it is among pet owners. Limiting your dog’s food to sensible portions and exercising your dog daily can help get rid of those unwanted pounds.

Supplementing your dog’s diet for a healthy coat

– Omega-3 fatty acids: These substances usually come from fish oils or flaxseed. They appear to have a positive effect on the coat, but too much of them is not a good thing. In extreme cases, they can reduce the ability of your dog’s blood to form clots. Keep these fats below 5 percent of your dog’s dietary intake of fat.

– Omega-6 fatty acids: These substances are normally found in meat and vegetable fats. Several types are available, but all are good for coats.

– Linatone, Mirra-coat, Missing Link and similar supplements: These supplements are blends of fats, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals that are supposed to make your dog’s coat more beautiful. I’ve never used them, but I’ve heard pet owners and breeders swear by many of them, so they’re worth a try if your dog’s coat is looking icky.

– Raw egg (or cooked egg): A daily dose of an egg is said to improve your dog’s coat.

I don’t recommend using raw eggs because of the chance of exposing your dog to salmonella; however, a cooked egg doesn’t hurt — unless your dog’s allergic to them.

– Vegetable or meat oils: Giving your medium-sized dog a teaspoon of vegetable oil (oil from meat works too) every day is a simple and cheap way to add Omega-6 fatty acids to his diet. Reduce the amount for smaller dogs; increase it for larger ones.

Warning!

All supplements add calories to your dog’s diet. Fat is the most nutrientdense at 9 kilocalories (standard calories) per gram. Protein and carbohydrates have 4 kilocalories per gram by comparison. So take these calories into account in your dog’s diet to avoid having a roly-poly pup with a great haircoat.

Don’t expect the change in your dog’s coat to happen overnight. Give the supplement at least six weeks to determine whether it’s going to help.

by Margaret H.Bonham