In This Chapter

- Understanding the psychology of dealing with a dog’s bad behaviors

- Crating your dog

- Correcting excessive barking

- Teaching a dog not to jump on people

- Housetraining a dog

Problem behavior is a very subjective thing. Of course, chewing on the carpet is a universal issue, as is housesoiling, but many people enjoy a lively, spirited dog jumping on them when they come home and don’t mind a few unearthed holes in the front yard. In this chapter, we put a few common frustrations under the microscope, looking at each from your dog’s perspective and offering simple straightforward remedies if, in fact, you’re seeking one.

Personal Philosophy and the Problem Dog

Consider two 4-month-old Cairn terriers who have started to do what growing terriers normally do — namely bark at every sound near your door, your window, your front walk, your street, your city. Remember, terriers are born to bark (see Interpreting Your Dog’s Breed-Specific Traits). Whether any given behavior that a dog displays is a problem is a matter of psychology — not psychology of the dog, but rather the psychological reactions of the people who live with and interact with that dog.

Sonya Brown is a young woman working her way up in an advertising firm. She has been living with one of these terriers, Toto, for nearly eight weeks, and she’s beginning to think that purchasing this lively puppy was a major mistake. She wanted a playful and affectionate dog, and Toto is certainly that. However, the dog’s continuous barking is becoming very annoying. Toto barks at everyone and everything, and it seems to her that she can no longer have a phone conversation with friends or business associates without being interrupted by her noisy dog.

Compare this to Sibyl White, a school teacher, who bought Toto’s littermate. This pup, Ozzie, was supposed to keep her semi-invalid mother company, especially while Sibyl was at work. Sibyl’s mother, Edith, was always a timid woman, and she became anxious about moving to the city to be with her daughter after her husband died and her health became worse. Edith had heard stories about how urban gang members and hardened thieves would break into homes that they thought were unoccupied or easy marks and often injure any occupants that they found. For this elderly woman, Ozzie’s alertness and noise were a great comfort, and, when not on alert, he would provide her with another form of comfort by resting close to her and allowing himself to be petted. Edith showed Sibyl an article that said that the likelihood that a home would suffer a break-in was massively reduced by simply having a dog that barked inside — regardless of the size of the dog. Sibyl could not remember her mother feeling this secure since she had moved to the city. With each outburst of barking, Edith would say, “Ozzie’s just doing his job. He’s letting them know that this house is protected.”

When mechanics conquers psychology Many times a mechanical solution is better than a behavioral solution, so it always helps to look at the possibility of changing the environment rather than the dog. Consider the following quick mechanical solutions to common dog behavior problems:

None of these solutions require a Harvard degree. Look around and see whether you can change the environment to quickly eliminate the unwanted behavior, and you may be able to save lots of training time or the cost of hiring an animal behaviorist. |

Both dogs are exhibiting the same behaviors. However, Sonya considers the behavior a problem while Sibyl feels that she has the perfect dog for her situation. The issue isn’t just what the dogs are doing, but more importantly, it’s how the dogs’ owners interpret and respond to the behavior.

No matter what kind of behavior problem your dog has, the options open to you are the same ones available to everyone:

- Live with the behavior. Obviously, if the behavior isn’t bothering you, as in the case of Sibyl and her mother, you don’t have a problem, and life can go on undisturbed. If the problem bothers you a little, then you can reorganize yourself and your environment to eliminate the immediate annoying effect of the behavior and be satisfied with that. Thus, if Sonya normally talks on the phone in the kitchen where Toto barks at the kitchen window, she can simply walk into the living room.

- Let the dog continue the behavior, but change how you feel about it. Changing a person’s attitudes and emotional responses to a dog’s behaviors is sometimes easier than you may imagine. For example, Sonya is a woman living alone. Perhaps if she were shown that article about how a barking dog reduces the rate of burglary and home invasions, then she might come to be comforted at the sound of Toto’s protective barking.

In our casebook, we have an example of changing attitudes toward a dog’s behavior involving a woman named Sharon and her manic retriever. Sharon’s pet was a Labrador Retriever named Magnet who, like all Labs, was extremely sociable and loved to retrieve. Magnet would drive Sharon crazy by picking up anything that he found on the floor and carrying it to her. Plush toys, stray slippers, socks, and magazines all ended up being offered to her. Then one day Magnet showed up with a pair of glasses that Sharon’s daughter had dropped, and another day he appeared with the car keys that she had been frantically looking for. It was then that Sharon realized that perhaps this behavior was not all bad. She has now even turned Magnet’s retrieving behavior into a game. She’ll walk into a room and happily call, “Magnet, find stuff!” and the dog scours the floor for anything laying around. It helps her keep the house neat, recover lost items, and redefine her dog’s behavior so that it’s no longer a problem but rather simply something that her dog does.

- Don’t change the dog’s behavior, but change the environment so that the behavior is limited, blocked, or is no longer seen as a problem. Many people, when confronted with a behavior problem, tend to focus too much on the behavior. Consider the story of Kevin and Noodles.

Kevin shared his life with a lovely, though garbage-obsessed, collie, aptly named Noodles. In every regard, Kevin loved his dog, though he was plagued by the frustration of her garbage escapades each morning when he left to run errands. No matter how long he’d be out, he’d come home to find the kitchen floor strewn with refuse. Though he had attempted every remedy from yelling at her to dragging her over to the scene and hitting her, nothing worked.

However, the real solution was easy and obvious, once Kevin was convinced to look at his own involvement in this cycle. Because Kevin’s reaction frightened Noodles, she grew more nervous as he got ready to leave. Equipped with more appropriate toys like chews and treat cubes, Kevin was also encouraged to take one simple step that cured the issue in one instant. He purchased a garbage can with a latched lid.

- Change the dog’s behaviors so that they match what you believe to be appropriate. Actually, this approach is the psychological or training option that most people immediately think about. The rest of this chapter focuses on solutions of this sort; however, note that you have to make certain choices when you decide to change the dog’s behaviors:

- How much time do you want to spend? Often, completely changing a dog’s behavior can be time consuming or involve an expensive dog trainer.

- How drastically do you want the behavior changed? Often, a small amount of training can greatly reduce, but not completely eliminate, a dog’s problem behavior.

Suppose that your dog is messing in the house every day – obviously a problem. Do you require that your dog never, ever eliminate in the house again, or can you put up with one accident every month or so? The first solution may be very laborious and time consuming, while the second may be accomplished quite quickly. Of course, adopting the second alternative may require that you also have to change your attitudes a bit to accept an occasional transgression by your pet.

- Get rid of the dog. Your original reason to get your dog was to improve your life and give your dog a good home. If neither is the case — your life quality is not great and your home is less than ideal for a dog’s lifestyle – then it’s time to rethink matters. If you’re unwilling to cope with problem behaviors, to take the time to modify them, or to change your attitude to accommodate such a situation, then everyone may be better off if you found your dog a different household that will appreciate all her special qualities. It’s a difficult choice to make, but please keep your family’s and your dog’s interests and happiness at heart.

TipIt may well be that you got the wrong breed of dog for your needs and living conditions (such as Sonya who may be better off with a breed of dog that seldom barks), or, sadly, you may be at a time and place in your life where you’re better off without a dog.

Denning Your Dog

Having an enclosed area, such as a crate, sectioned off playpen or room, or stationed corner (see Seeing Life from Your Dog’s Perspective ), is useful as it provides your dog with a sense of security and comfort in your home. Your dog’s wild cousins lived in a den, either a hollow area (enclosed on all sides except one), cave, or a deliberately dug-out hole. This den provided comfort and security, and was a safe place to go when its occupants chose to be undisturbed. Inside your home, the crate or small-secluded area is simply a substitute for the den.

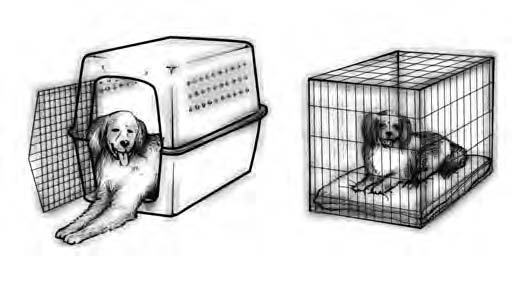

Crates come in several materials and sizes, as do playpens. Whether you purchase or manufacture a den, or choose to enclose your dog in a small gated room, the area should be large enough in which to stand, turn around, and lie with outstretched paws. Place a soft bedding material in this area, provided your dog doesn’t chew or soil it.

RememberAlthough the crate (such as those shown in Figure 13-1) may look like a cage to a human, most dogs actually like them. Locate your crate in a familiar room, ideally placing it at your bedside at night and in a populated room during the day.

Figure 13-1: Typical kennel crates. Drape a sheet over three sides of wire crates to give it a denlike feeling.

The fastest way to encourage your puppy into his kennel is with food lures and a reward system. Once all hesitation is gone, direct your dog with a verbal cue, such as “In your house.” If you’re teaching an older dog, gradually increase the amount of time she’s expected to stay. Initially shut the crate door for just a minute or two and reward her for her accomplishment. Next, close the door and try leaving the room for a few moments. Return, give her a treat, and let her out. Then gradually increase the time away from your pet.

Warning!If your new puppy or dog is whining in the crate at night, determine whether anything is wrong or if she’s in physical discomfort. (Puppies under 12 weeks should be taken out in the middle of the night if they whine.) If nothing is wrong, ignore your dog because your attempts at comforting provide attention, which is rewarding to the dog, and thus the whining will become a habit.

Silencing Excessive Barking

Rewind to ancestral times, and you’ll quickly note that a dog’s barking was one of the chief assets of the canine/human union. More vocal alert than a wolf who howls at night, a dog’s bark provided warning to our primitive ancestors.

Though dogs still bark out their alarm or warning, few people appreciate the depth of their skill and devotion to this task. Furthermore, dogs that bark continuously at night, in their yard, in an empty home or apartment, at every dog or person that they see, and so on are considered a nuisance and often bring unwanted attention from the community and even fines for breaking anti-noise bylaws. This situation may pose a problem for the ever-eager, constantly vigil, and slightly bored dog of our modern era.

Every dog behaviorist’s casebook is filled with complaints that go something like this: “My dog barks at every little thing, even when I’m at home. She stands at the door or window and barks. I tell her to stop, I shout at her to be quiet, but nothing stops her. I think my trying to correct her may even be making her barking worse!”

RememberDogs bark as part of defending their territory, so it’s quite natural for a dog to bark more when he’s at home than when he’s away from home. It is important to understand what is triggering the barking response and what the dog is trying to tell you.

RememberBarking is an alarm sound (see Communicating with Your Dog). There is no threat of aggression signaled by the dog unless it’s mixed with growls.

The most common bark heard around the house involves rapid strings of two to four barks with pauses between each set, sounding something like “Woof-woof . . . Woof-woof-woof . . . Woof-woof.” You can translate this classic alarm bark as, “Call the pack.

Something is going on that should be looked into.” It indicates that the dog senses something nearing or outside the home and is trying to bring it to the attention of his pack and pack leader. The problem is that most people fail to recognize that the dog is trying to communicate to them and that what’s required is an answer.

Because the dog is being noisy, they usually try to silence their pet by shouting, “Be quiet,” “Stop that noise,” “Shut up!” This response is exactly the wrong one because the dog interprets your yelling as “Woof-woof . . . Woof-woof-woof . . . Woof-woof.” Instead of reassuring him, your involvement now confirms that you feel the same way that he does, so don’t be surprised that your dog feels he’s done the right thing and continues to bark — perhaps even louder. After all, you’re encouraging it!

TipThe appropriate way to stop his barking is to recognize that his noise is really a signal with a specific meaning. He wants you to investigate something. A more appropriate response is to look out the window or check the door where he’s barking. Then calmly tell him, “Good guarding,” give him a pat, and call him back over to you when you sit down again. He’ll interpret this sequence as, “I asked the leader of the pack to check things out, and my leader sees no problem. Therefore, I don’t need to continue barking.” Eventually, “good guarding” will quiet him and bring him to your side.

Notice that this solution doesn’t prevent barking. It’s normal for your dog to bark at animals and people that come onto your property or approach your door. Many cities have gone so far as to define this type of barking as “reasonable” when they’ve drafted laws concerning nuisance barking. You don’t want to completely eliminate the barking because it serves the useful purpose of alerting you to someone’s presence. However, you do want to stop it quickly and keep it under control, and communication is the way to do so.

Dogs that bark at neighbors

When your dog barks at a neighbor, he’s protecting his territory. Although his protection is warranted, the neighbors are there to stay, so it is better for everyone if you resolve this daily confrontation.

The trick is to arrange things so that the neighbors are no longer seen as trespassing marauders. Follow this simple three-step process:

- Introduce your dog to the neighbors on common or neutral ground, such as the area between the two properties.

Let the dog make the first move to sniff or greet your neighbor, who should stand still and not stare or reach until the dog has settled down. If your dog is fearful or overly aggressive, handle him on a leash and bribe his acceptance of them with a treat or toy. If he doesn’t relax, seek professional help. Don’t force him onto anyone, or he may react in self-defense.

- Have the neighbors come into your yard and stay for a bit.

Be sure that they interact with your dog. Have them use his name, call him a few times, offer him treats, play a bit of fetch, and so on.

- Have the neighbors return to their own yard with some of the treats that you have provided and then have them approach the fence.

They should talk happily to the dog, use its name, and offer him a treat through the fence. If it is a solid fence, any crack or knothole will do.

TipRemind the neighbors that if your dog does bark at them again, they should just use her name and approach the fence to say “Hello.” Remember, the dog usually only barks to warn of strangers, and now the neighbors should no longer fit into this category.

Excessive barking in the yard

Many dogs bark when left alone outside. Though barking can drive everyone to distraction, the typical approach of screaming rarely has the desired effect. The solution lies in examining why this barking occurs in the first place.

First recognize that dogs are social animals and are most comfortable and happy when they’re in the presence of others, whether people or other dogs. Second, consider your home as your dog’s den. Isolated from entry, your dog is frustrated, lonely, and bored, which can easily escalate to fear and insecurity if the surrounding environment is noisy or unpredictable.

The solution to this kind of barking is simple: Limit your dog’s outdoor isolation and bring the dog inside the house. Even if your schedule leaves him alone, you can enclose him in a crate or room and be assured that he’ll be much happier surrounded by sights and smells that are associated with his family.

RememberIf your dog does bark when you’re away, remember that a barking dog in a home reduces the rate of burglary to one-seventh of the normal rate. A barking dog can be quite useful because he’s now protecting your home!

Other nuisance barking

Dogs that love to bark — at moving objects, noises, and sights — and those who seem to bark just for the fun of it are the hardest group to quiet. The first step in controlling the persistent noise is to help bring attention to the sounds they’re making. Like chatty children, their motto may be, “I bark, therefore I am.”

The most clever and quickest way to turn off unwanted barking is to teach the dog to bark on command! One simple way to do so is to follow this training routine:

- Place your dog on leash and attach the leash to a fence or other stationary object.

- Stand a few feet away and tease him with a toy; when the dog gets excited and/or frustrated and starts to bark, immediately give the direction “Speak” and then give the toy as a reward.

- When the dog is consistently barking to the word “Speak” with the toy as a reward, switch the reward — first to a treat and later to a verbal praise.

- At the end of a barking tirade, say “Quiet” and then reward him; after your dog recognizes “Quiet,” move a short distance away.

Learning this step may take several repetitions. Be patient.

- When your dog responds appropriately to your commands, return to give the reward.

Eventually, you can move farther away and change to verbal rewards.

- Finally, with a pocket full of treats, take the dog out to situations where he normally barks; each time he begins to bark, vary the duration he’s allowed to sound off before instructing “Quiet.” Reward his cooperation immediately.

You can use the “Quiet” command as an off switch to stop most barking when you’re present. However, the length of time that the dog stays quiet will depend upon what you do next. Distracting the dog with play, attention, or a brief training session can help keep him focused on you rather than the bark-inducing situation. Eventually, his silence will evolve into longer periods of silence and greater self-control on the part of your pet.

Barking in the car

Dogs often turn into frantic barkers when left alone in the car due to two factors:

- A dog’s natural instinct when something startles or frightens them is to run away, which can’t happen while riding in a car. Barking is an attempt to call his pack mates back for help.

- The car becomes the limits of their territory, and its compact area must be vigorously defended. Because no help is arriving, the barking may change to a combination of warning and threats. When the object that worried him, such as a person walking by, moves away, it rewards your dog and makes it more likely that he’ll bark again in a similar situation.

Warning!Manic behavior in the car can be annoying and frighten passing pedestrians. If the car is moving, the dog noisily ricocheting around the interior can distract the driver and even lead to accidents.

The simplest solution to this problem actually takes less time to present than it takes to describe the behavior problem itself. This is the perfect place to use the dog’s kennel crate. If you have a hatchback car, van, or station wagon, just pop the kennel crate in the back. If you have a sedan and a small- to medium-sized dog, you can put the kennel crate on the back seat and secure it from moving during sudden stops by using a strap or the seatbelts. Now all that you need to do is to put the dog into the crate with a treat and a chew toy. The kennel walls will screen many of the exciting sights from view, which helps some dogs. However, the major benefit is that the dog understands that the crate is his den, and he’s always safe, secure, and undisturbed in his den. With no threats or anxiety, he has no need to bark, and the problem is solved.

Chewing

Chewing is as natural to dogs as touching is to kids and people. To recognize your dog’s motivation in chewing, consider his age, as well as outside disturbances that often trigger the chewing in adult dogs:

- Curiosity: Very young puppies (up to 12 weeks) mouth to experience new objects, much as young babies want to touch and hold anything within reach. The best approach is to puppyproof your home, clearing shelves and anything else within your puppy’s grasp. If he gets an object, calmly remove it and replace it with an appropriate item, such as a treat or chew toy. Don’t issue even a verbal admonishment at this age. It will make no sense and create friction in your household; it’s like yelling at a 6-month-old baby for pulling your hair.

- Teething: Young puppies do teethe, just like children. Their “milk teeth” (or first set of choppers) are displaced by the arrival of their permanent set, causing itching, pain, and sometimes bleeding. This is usually about the time your puppy may start chewing the furnishings or molding. Frankly, this reaction makes perfect sense: If he can’t locate a toy immediately, at least he always knows the whereabouts of a table leg or wall. Regardless, you need to arrange areas for your dog in each room, equipping each spot with desirable chew toys (and tying them down so they’re not carried off). In addition, spray your items at risk with a distasteful solution.

The teething stage is also the time when many dogs learn the artful game of grab-and-go, and who can blame them? It’s fun and exciting to grab an object and entice you to chase after him for it. Because the behavior is primarily attentiongetting, the best response is to simply walk away or leave your home for three minutes. At another time, prompt your dog’s interest by placing the object nearby and walking him toward it on leash. The moment he shows interest in it, tug the leash back and say, “No.” Then direct your dog to a more appropriate activity.

We often liken excessive chewing in adult dogs to an adolescent acting out: The behavior itself represents a deeper unrest, and the worst thing you can do is scold your dog after the fact. To address this issue, you must first determine whether the behavior is ageappropriate; if not, ask yourself what environmental disturbances or changes in your relationship may have prompted this restless behavior. If chewing has evolved recently, consider whether it’s occurring due to boredom, frustration/anxiety, or attention seeking. (We cover alternatives to these situations in Countering Anxiety-Based Behavior and Understanding and Resolving Aggressive Behavior.)

Putting a Damper on Jumping

In movies and cartoons, it may be funny when the big dog heads directly to the woman in white clothes, jumps up to greet her, knocks her down, and leaves muddy footprints on her dress. In real life, however, this behavior is rarely welcomed. How you stop it depends on what’s prompting your dog to jump up in the first place.

Competing behaviors To stop a dog’s annoying jumping, all that you need to do is to find a “competing behavior” that is incompatible with the act of jumping. In dogs, the easiest competing behavior for jumping and a variety of other active behaviors is to have the dog sit. One reason why it’s easy is because most people have already taught their dog to sit when given a verbal command or a hand signal. Obviously, if the dog is sitting, he can’t be jumping at the same time. To get rid of jumping behaviors as a greeting, simply tell the dog to “Sit” when you walk in the door or greet the dog in the morning. Praising, petting, or offering a bit of a treat serves as a reward. Another example of a competing behavior is when dogs jump onto the furniture. They’re seeking a soft comfortable place to rest, so providing a dog bed or floor cushion in the same room is the solution. The dog must be shown this alternative and placed there if he jumps on the sofa. Obviously, the dog can’t rest on the sofa and his bed simultaneously! |

Your dog may have many reasons for jumping up. If jumping occurs during greeting rituals, his intention is to make contact with your face.

RememberBecause attention (negative or positive) reinforces behavior, many people unintentionally reward jumping. Any reaction that involves touching is considered interaction. Do you find yourself pushing or grabbing your dog’s coat as he leaps about? You may be encouraging this behavior.

Warning!Some training books suggest harsh measures, such as kneeing the dog in the chest when he jumps on you. Such methods don’t work very well, and even when they do, they only stop the dog from jumping on the person who punishes him for it.

Greeting jumping

It’s important that you praise your dog for sitting instead of jumping. However, it’s equally important that the dog be completely ignored when jumping. Don’t say, “Bad dog” or “No” because that means that you’re paying attention to him, and attention is rewarding. Don’t push the dog away because touch is rewarding. Simply act as if the dog isn’t there, except when you’re telling the dog to sit. When the dog does sit, lots of attention and rewards are the result.

TipIf ignoring your dog is ineffective, fold your arms over you face and continue to ignore him until he’s stopped and calmed down. Redirect him to sit or to fetch a toy.

Company jumping

If your dog is jumping on other people and you’re present, the solution is simple — just tell your dog to sit before he jumps, reward him, and then allow your visitor to pet him or give him a treat for sitting politely. If he’s too rambunctious, keep him on a leash, either stepping on it to prevent interference, holding it, or tying him back away from the door until he’s calmed down.

Of course, that approach doesn’t work when you’re not around and your visitors don’t know that they must give the “Sit” command to prevent being jumped on. There is an easy solution, however.

Most people train their dog to sit when they say the word or give a hand signal. What you must do is train the dog to sit to an additional hand signal that can be used during the greeting rituals. In this case, the hand signal that you want to use is to have both hands flat, palms up, facing the dog, as shown in Figure 13-2.

Figure 13-2: Hand signal for “Sit” to reduce jumping behavior

To train the dog to respond to this hand signal is easy. Stand in front of the dog, say “Sit” (which he already understands), and give the hand signal. Give him a treat when he responds. Once he gets used to seeing the hand signal along with the verbal command, try just the hand signal and see whether he’s figured it out. If not, keep practicing using both the hand and voice commands. When the dog understands that when both hands go up, he’s supposed to sit, you’re then ready for the dog to meet strangers, even when you’re not present.

The reason that this new hand signal prevents jumping is that it’s the same as the defensive motion that most people make to protect themselves when they’re afraid that something (like a large dog) is about to collide with them. So your visitor sees your dog approaching and makes automatic defensive hand movements (with no need of instructions from you). Your well-trained dog interprets this as a “Sit!” command, and the problem is solved. Remember, a sitting dog is not jumping up.

Housetraining

Though several scientific studies show housetraining to be the No. 1 frustration of dog owners, it doesn’t take a pie chart or graph to convince you that a dog that is not housebroken isn’t any fun. If you’re still struggling in this area, help lies just ahead.

If your puppy is young and is used to sleeping in his kennel, your efforts will be straightforward, as he’ll instinctively avoid messing in it. One of the first lessons the puppy learns from his houseproud mother is the need to be clean in the sleeping area, which she teaches by consuming all the waste that the pups produce.

RememberEvery facet of your dog’s behavior draws on his evolution. Before domestication, birth dens were kept clean to remove the scent of droppings that could lead a predator to a young litter of defenseless pups.

If your puppy is eliminating in his kennel crate, it may simply be too large. A large crate allows the pup to eliminate at one end and rest in the other. The goal is, of course, for your puppy to build control and not go until he’s released from this confinement. If you purchased an adult-sized crate, purchase or fashion a barrier to limit your puppy’s free space. Inserting a cardboard box of the right size to leave room only for the pup to turn around and lie down is an easy solution.

Bathroom buddies Experienced dog owners will tell you that it is a lot easier to housetrain a puppy if you already have a housetrained dog in the home who knows the routine. The trick is to let both the older dog and the pup out at the same time or take them on their walks together. The puppy watches the adult dog and, from simple observation, learns what is expected of him. This advice leads to an obvious recommendation. If you have an older dog in the house and fear that he is nearing the end of his life, it may be helpful to bring a new pup into your home before the older one dies. This early arrival gives the puppy a chance to be mentored in house cleanliness and other basic skills by the already trained senior dog. A side benefit is that having a new pup in the family often improves the quality of life and the activity level of the older dog and may even extend his life. To insure you choose a puppy who is compatible with your older dog, please refer to Identifying Your Dog’s Individuality. A dominant puppy can emotionally undo a peace-loving senior. |

The housetraining routine

Routine is a key feature of housetraining. Draw up a master schedule and insist that everyone take part in ensuring adherence. Schedule feeding times, toilet breaks, and organized play periods. Here’s a quick list of tips:

- Young puppies and untrained dogs need to go outside after napping or after being crated for a while, because increases in activity after a period of quiet often trigger elimination. This means that the first thing in the morning, immediately after you take him out of the crate, he has to get a chance to eliminate. After a long night, puppies often can’t even make it to the door before they have to go, so you may have to carry him to the door for a week or so.

- A young puppy hasn’t developed strong bladder muscles and must be taken out frequently, particularly after eating, drinking, play, resting, and isolation. A young puppy (6 to 14 weeks of age) may benefit from being taken out eight or more times a day. This number will gradually reduce over the next six months.

Warning!If your dog is eliminating very frequently, he may have an internal infection or parasites. Speak to your veterinarian immediately.

- Bring your dog to the same area to relieve himself. You may highlight this area with pine chips or designate a specific tree or outcropping. Have a fenced-in yard? Until your pup is housetrained, you’ll still need to accompany him to encourage and reinforce his habits.

- Don’t confuse your goals. When you take your dog out to potty, bring him to his area and ignore him until he does his business. Don’t give him walk time or play time until afterward.

- Teach your dog word cues and routines to highlight your participation, such as ringing a bell or barking before you go out. Say, “Outside” or “Papers” as you escort your dog to his area. Then cue him with another phrase, such as “Be quick” or “Get busy,” as he’s in the process of eliminating.

TipBy repeating a phrase each time your dog eliminates, you’re indicating what you want the dog to do, and ultimately he can learn to eliminate on cue.

- Once your dog has eliminated, take time out to reward him with your attention, a fun game, or a walk. If you rush back inside immediately, your dog will learn to delay eliminating in order to spend more time outside with you.

TipMost puppies can hold their bladder muscles for six to eight hours. Take your puppy out just before your bedtime, even when you must rouse him from a deep sleep.

When accidents happen

Face it — accidents happen. Although dogs catch on to the housebreaking routine quickly, no one is immune to an occasional lapse. Accidents happen for a variety of reasons:

- The dog was isolated too long or not given adequate time to relieve herself during the last outing.

- He’s suffering an infection or illness.

- He awakened from a nap or had a large drink of water and no one noticed, so he wasn’t let out.

- You got home later than usual, and the dog couldn’t hold it.

If the dog messes, don’t hit him, yell at him, or rub his nose in it. A dog rarely makes the connection between your punishment and his earlier behavior. Such heavy-handed behaviors only teach the dog to be afraid of you. If you catch the dog in the act and punish him, all that you may have taught him is to make his messes in hidden places out of your sight.

If you actually catch your dog in the process of eliminating inside the house, interrupt him and take him outside to the proper place (without harsh words or punishment). If he eliminates outside, praise him. Remember to be patient; some dogs take longer than others to housebreak.

Your best course of action when faced with an occasional mess is to simply clean it up. Then use a commercial odor eliminator (many are enzyme-containing products) or simply clean the area with white vinegar or rubbing alcohol. These cleaners kill any trace scents that may trigger elimination.

Laugh a little Your interpretation and response to your dog’s behavior really determines how disruptive his delinquency is to your life. Often, a sense of humor will save your relationship with your pet. One day, Stan had done some shopping and then left the bag of groceries on the kitchen counter while he went off to a meeting. When he returned, the kitchen was a disaster area. His retriever Dancer had pulled the bag off the counter and eaten a bag of cookies and a loaf of bread from it. In the process, a plastic bottle of cola and another bottle of pink liquid stomach upset remedy had split open, covering the floor with a sticky brown and pink mess with lots of crumbs floating in it. Meanwhile, Dancer stood in the middle of this mess with his stomach distended and rumbling. Obviously, disciplining Dancer for something he’d done a couple of hours ago was useless because he wouldn’t understand the connection. Stan had the following alternatives:

So he laughed. It doesn’t mean that he doesn’t care or likes cleaning up sticky messes, or that he’ll ever leave things like that on the counter edge again. He laughed because it was too late to do anything but clean up and because he knew that this would be a funny story to tell to his friends. Anger only confuses the dog and weakens your relationship with your pet. It doesn’t solve any problem. Before punishing the dog for a transgression, ask yourself, “Will I laugh about this incident later or when I tell it to someone else?” If the answer is yes, why not laugh now and then get on with the business of making things right again? |

Warning!Don’t use products containing ammonia, because it smells enough like urine that it actually attracts the dog to eliminate in that place again. Also, don’t let the pup watch you clean up because your activities may draw him back to that spot again.

For more information on housetraining, see Housetraining For Dummies (Wiley), by Susan McCullough.

by Stanley Coren and Sarah Hodgson