In This Chapter

- Interpreting what your dog is saying

- Decoding body language

- Listening for verbal clues

- Reading facial expressions

If your dog could talk as you do, she would have a lot to say, both good and bad. But alas, for better or worse, she cannot. Your dog’s brain, not her determination or will, limits her ability to use and understand human dialect. However, your dog can, and will, communicate in her own unique language, which we call Doglish.

Doglish consists of many elements, the least of which is vocalization. Unlike people, dogs watch more than they verbalize. In this chapter, we reveal how dogs use their body language (and at times, their voice) to convey mood and meaning.

An English to Doglish Translation

Imagine being a foreigner in a country where you don’t understand the language. Though you’d be eager to communicate, all your efforts would be thwarted by the language barrier. Now you know how your dog feels.

You can think of training your dog like teaching English as a second language: The better you know your dog’s native tongue, or Doglish, the easier it is to understand her behavior. More physically expressive than verbal, your dog uses her entire body to convey emotion: from the top of her ears to the tip of her tail. The following sections help you translate — by simply observing all elements of her body language — your dog’s mood, intentions, and desires.

Seeing Eye to Eye

Group interaction is the highlight of your dog’s day, and your eye contact is a sure sign of acknowledgement. Because your dog can’t comprehend frustration, your negative eye contact often gets interpreted as confrontational play. The result? Many negative situations are exacerbated.

For example, if jumping gets even a sideward glance, your dog will jump again to get your attention: a repeat performance is guaranteed. If stealing an object ensures a group chase, it will quickly become your household’s favorite pastime, at least from your dog’s perspective.

Fortunately, you can also use eye contact to encourage and discourage behavior after you realize how your dog processes your visual attention.

Here’s what you’re saying with your eyes, whether you realize it or not:

Tip– Engaging in excessive eye contact: If you stare at your dog in adoration, frustration, or merely out of habit, you look like a follower. Leaders lead; followers watch. Though quiet time and playful interactions may call for a visual connection, avoid staring at your dog.The more you look at your dog, the less she’ll look to you. Fortunately, the opposite is true, too: The less you look at your dog, the more she’ll look at you. Be a leader, not a follower — give direction, don’t take it!– Staring: Staring conveys a social challenge, so you’re best off avoiding this interaction altogether. Use the brush-off technique: If you’ve given her a direction, follow through by positioning her as you ignore her visually. If your dog is intent on this activity, see Seeing Life from Your Dog’s Perspective and Happy Training, Happy Tails.– Staring while ignoring your direction: One of two things is going on. Your dog may be trying to challenge your authority by staring at you as she deliberately ignores a direction. Don’t take this move personally — it’s just a test. Staring back, however, will bring you to her level. Instead, brush it off and position her.On the other hand, if your dog is young, new to your training routines, or simply insecure, she may stare at you in hopes for more direction. (You can tell the difference by her submissive posture: ears back, body curved down into a submissive pose.) In this case, position her calmly and consider using the luring technique described in Happy Training, Happy Tails to boost her confidence.– Ignoring your dog: Often, you can extinguish behaviors by simply ignoring them. Because your dog repeats any behavior (negative or positive) that gets your attention, try the opposite: Block facial interaction by folding your arms over your face. Your dog jumps — close shop. She barks for attention — nobody home. This easy-to-replicate response is a sure signal that the behavior gets decidedly less attention, not more.

TipIf your dog becomes persistent, it’s a good sign that your efforts are having an affect. Accustomed to your normal reaction, she’s determined to get your attention. Some professionals call this an extinguish burst, but we like to think of it as a sign of doggone determination!

TipLook at your dog when she’s cooperating, not when you’re giving her instruction. For example, when calling your dog, don’t stare at her. Either look at the ground (she’ll think you’ve found something interesting) or turn away as you call out her name. Your trailing voice will spark her curiosity.

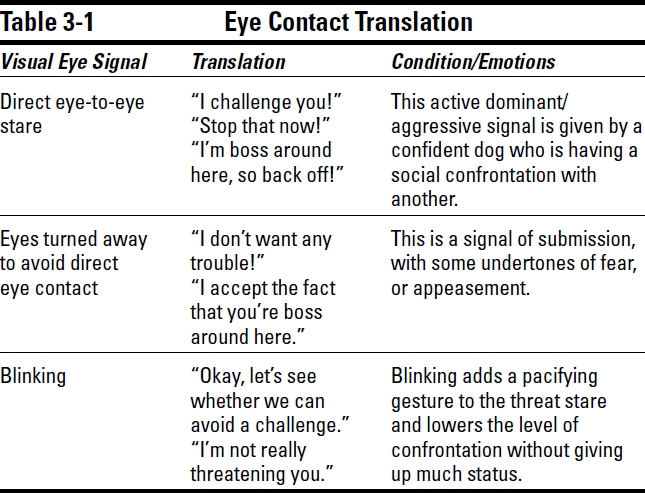

Dogs, like people, use eye contact to assess and reinforce status and other communications (see Figure 3-1). Table 3-1 identifies your dog’s thoughts.

Figure 3-1: Dogs also use eye contact to communicate.

How your dog views your language Are you convinced that your dog understands you — that she “knows” she’s done something wrong? Though her posture may look like an assumption of guilt, most dogs are merely afraid when humans berate them. Think about it. It’s likely that dogs interpret human yelling as barking. When vocalization is loud and excessive, it sounds frantic and bespeaks lunacy, not direction. Running at a dog is terrifying. Imagine some giant running at you for handling something you thought was the normal way of reacting. Your dog simply doesn’t respect material value. Hitting a dog? Anyone that hits a dog should be ashamed! Poor defenseless creature — the only lesson a hit dog will learn is aggression. A young or uncivilized dog doesn’t know right from wrong any more than a mole would know whether she dug in the wrong dirt pile. Fortunately, you can teach your dog what pleases you and how to contain specific impulses, but first you must learn to speak your dog’s language and respect how she thinks. |

Technical stuffThough you may not have paid much attention to the size and shape of your dog’s pupil in the past, this little disc communicates loads. The larger the pupil, the more intense your dog’s emotional state and arousal. A widening eye and pronounced round shape heralds a dominant or threatened individual. On the flip side, a small eye or squinting brow signals passivity and submission. Please reference the other components of your dog’s posture in this chapter for a more thorough examination of how body postures, eye expressions, and tail positions convey a dog’s emotion.

Just for funWatch your dog’s brow. Any action that you see in the forehead region conveys virtually the same emotional response as in a human’s forehead.

Interpreting Vocal Tones and Intonations

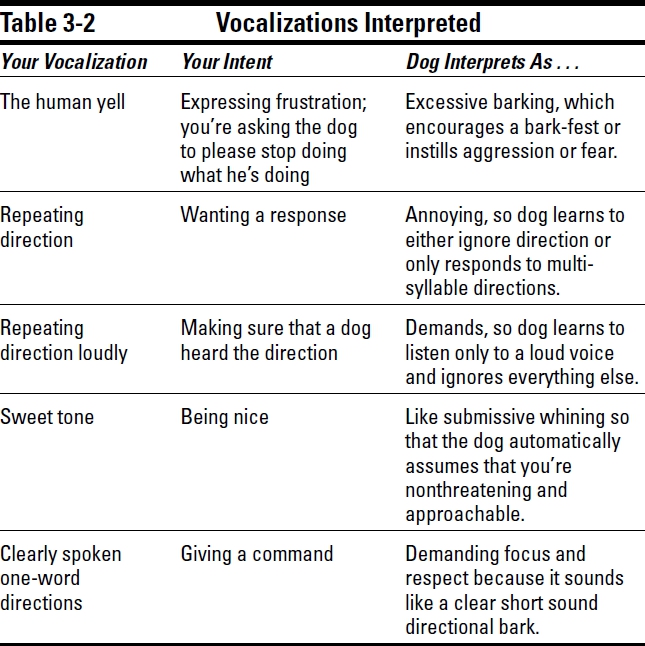

Dogs can’t process a great deal of chatter. They can’t talk, but they can communicate and respond to spoken directions that are given properly. Table 3-2 outlines what our dogs hear when we speak to them.

Technical stuffHumans learn primarily through auditory recognition: We listen to directions. Sight is secondary. On the other hand, dogs learn by watching each other instead of by listening or “talking.” Teach your dog hand signals for every verbal direction (“Sit,” “Wait,” “Down,” “Come,” and so on). See Happy Training, Happy Tails for a chart on corresponding hand signals.

Making the Most of What You Say

When training your dog, think of your efforts as teaching her the proper responses to each direction. Training doesn’t give you license to order your dog about: like a child, your dog is an individual and makes her own decisions. If you’re confident and supportive, she’ll respect you and take direction with joy. If you frustrate easily and are demanding, she may tune you out and run from you at every opportunity.

Here are a few more tips for communicating with your dog through words:

Tip

- Think of directions as though you were your dog’s teacher or coach. Say your directions as you would tell a player to move to the left or as though you were telling your class to have a seat or come to the blackboard. Nothing should be spoken in a tone too dramatized or placating.

- Give directions once. If your dog doesn’t know the direction, simply position her as if she’s not paying attention.

- Don’t yell at your dog. If you’re frustrated, you may speak sternly, but keep it short. The phrases “That’s unacceptable” or “shame on you” spoken and properly timed convey your disapproval without fanfare or confusion.

- Don’t bother modifying your voice. Speaking in a deep voice may not come naturally to you, and if you’re faking it, you’ll likely see your dog giving you the teenage version of an eye roll.

For basic training exercises, see Happy Training, Happy Tails.

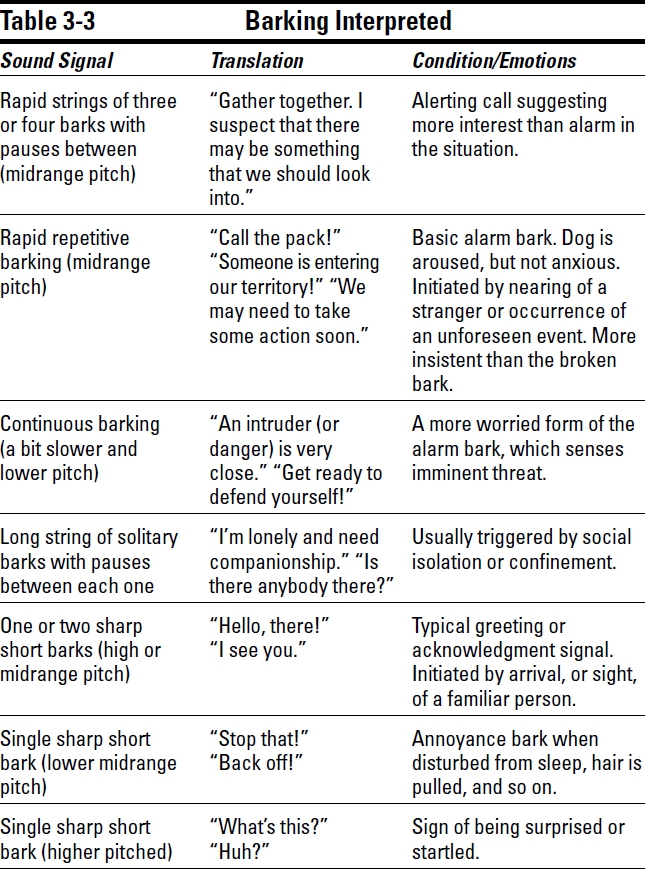

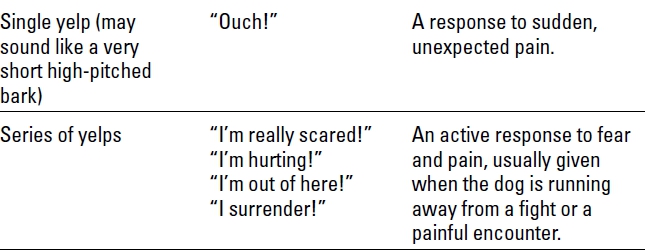

Listen to Your Dog’s Voice

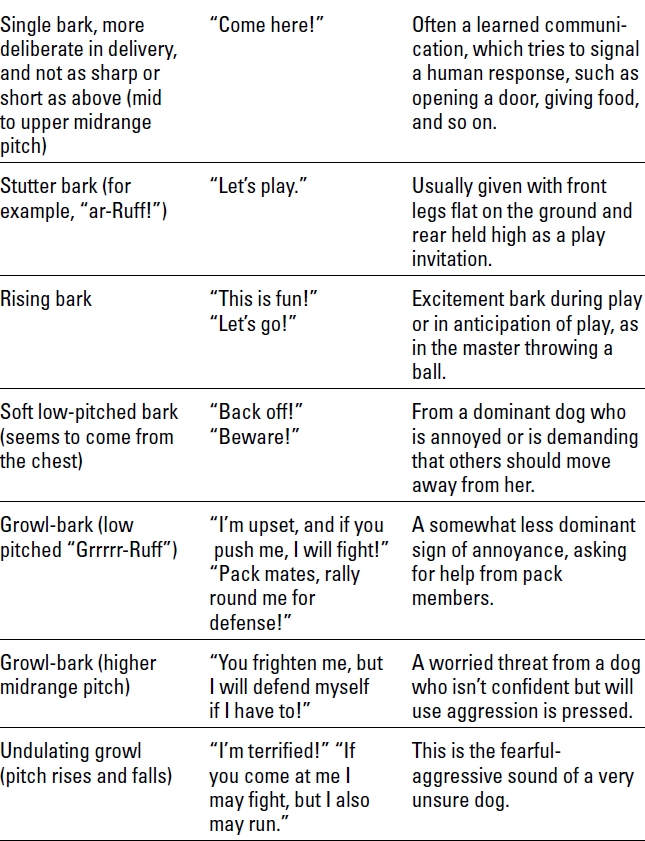

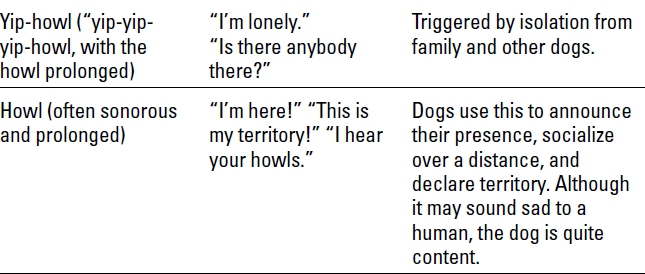

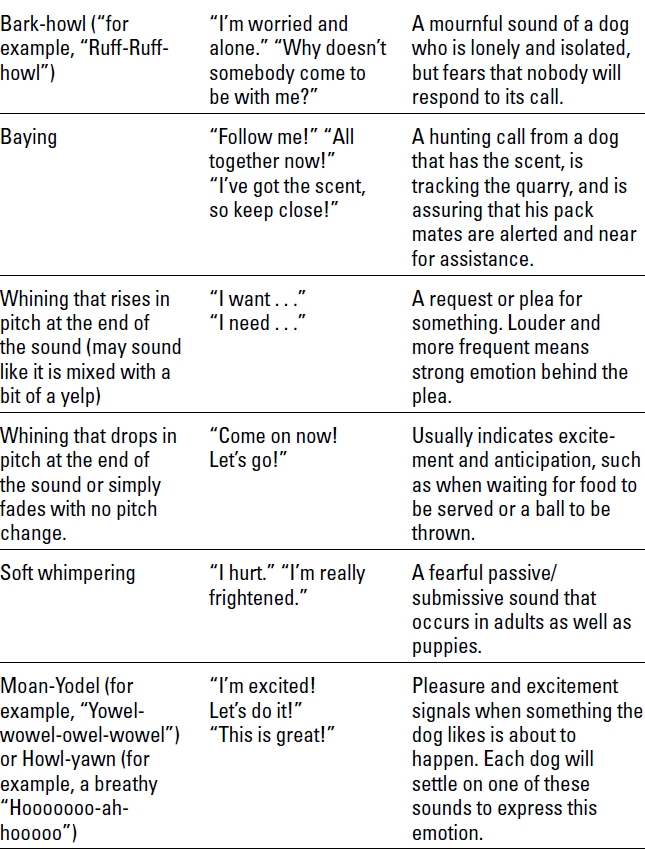

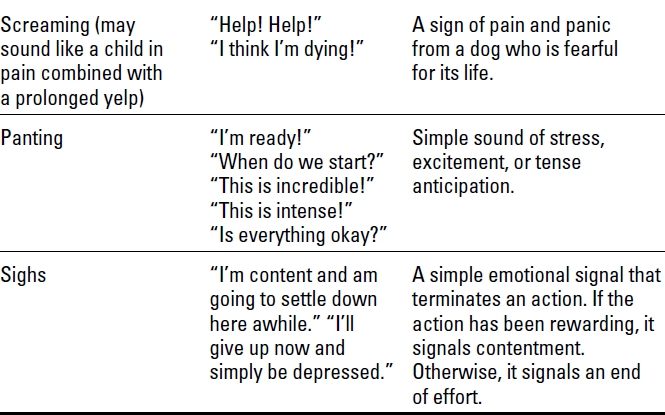

Though your dog won’t “talk” to you in English, you can interpret both her intentions and immediate desires if you know what to listen for. In Table 3-3, we outline the range of sounds dogs make, providing you with a human translation and the moods behind every utterance. Overall, a low pitch indicates a more dominant or threatening stance, whereas a high pitch conveys just the opposite — insecurity and fear.

A dog whose pitch or vocalization varies is emotionally conflicted. Unsure and unable to properly interpret a situation, this dog needs a lot of direction and interference to feel secure. (Refer to Happy Training, Happy Tails and Countering Anxiety-Based Behavior for more information.)

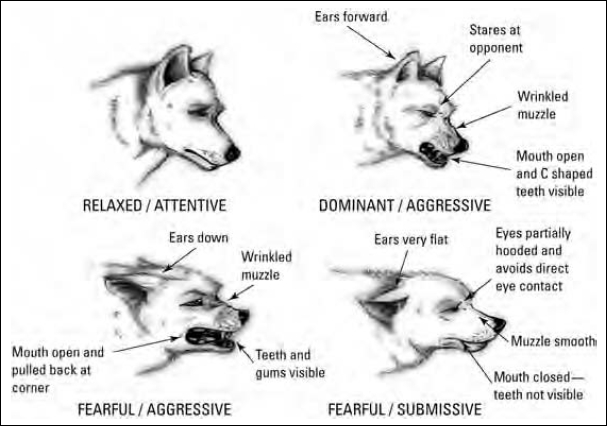

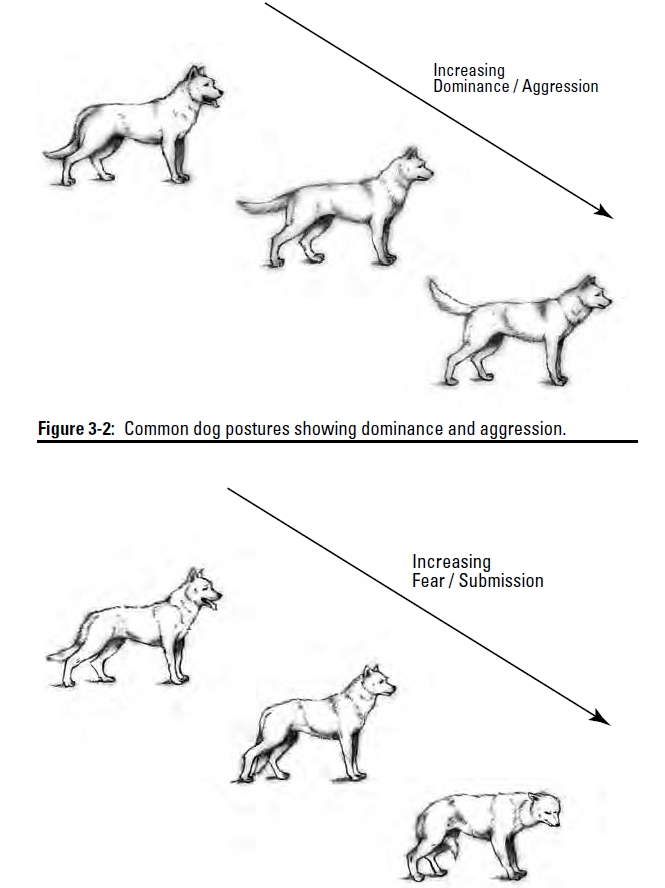

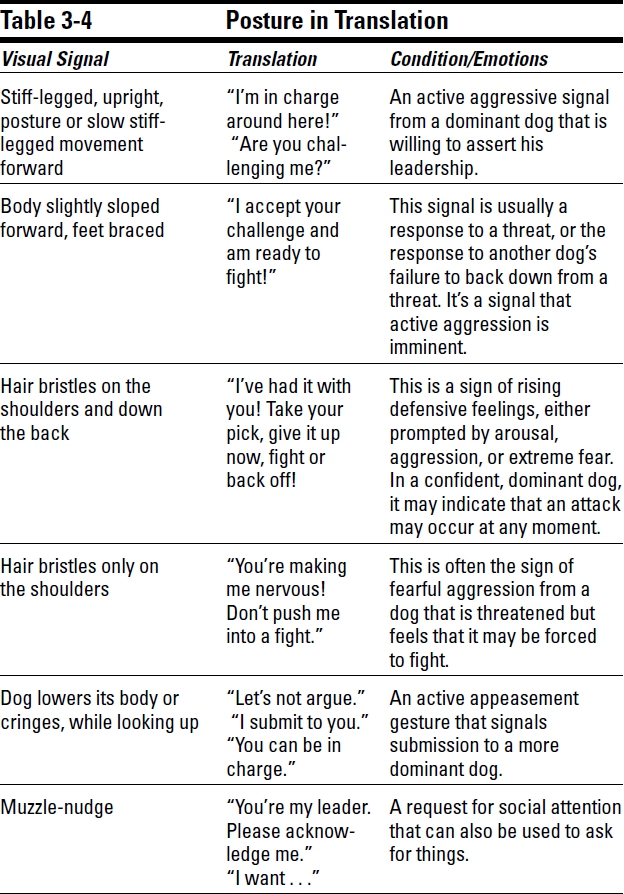

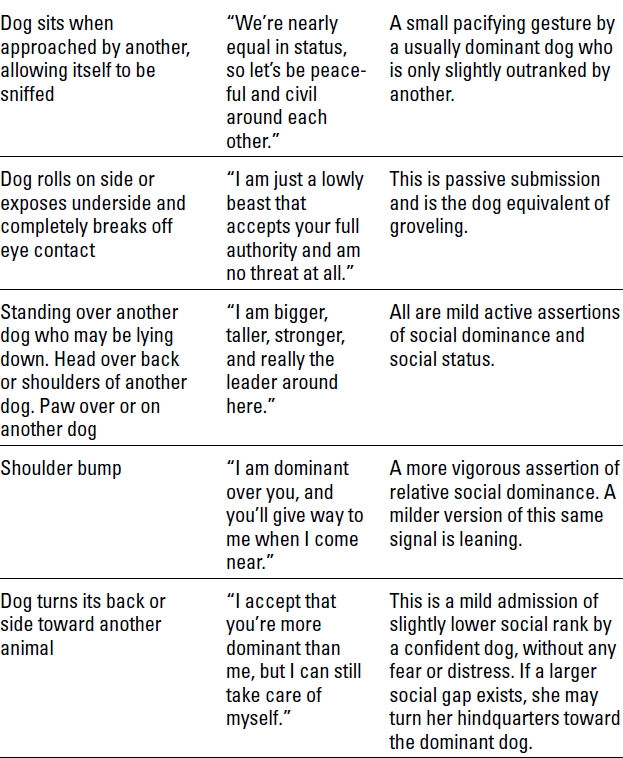

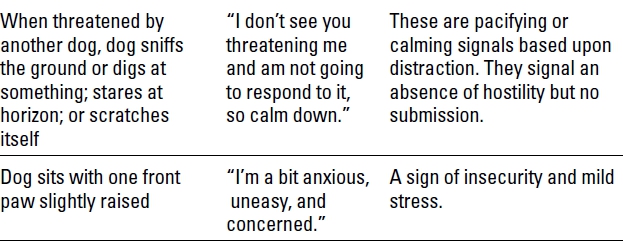

Reading Body Talk

Your dog is communicating a lot through her body postures and also tuning in to your body language more than you might imagine. Regulating how you hold your posture and recognizing your dog’s body language can enable a fluent dialog between the two of you. Figures 3-2 and 3-3 illustrate common dog postures, and Table 3-4 highlights their translation.

TipRemember that if your dog is shrunk and low, she’s feeling insecure or scared. If her weight is pitched forward, she’s confident, on alert, or in defense mode. If her head is hung low, but her body is relaxed, the message is loud and clear: “I’m exhausted!”

General rules apply to body posture for both of our species. An alert upright posture conveys confidence. A sudden rise in stature often underscores a need to gain control or dominate others. A fully directed body is often used to issue a threat (although in young or submissive dogs, it’s used to elicit play or pity). When normally socialized dogs meet in an open area, they approach at side angles, which is pacifying and conveys a willingness to greet one another and get along.

Figure 3-3: Common dog postures showing fear and submission.

Warning!Professionally, we’re often asked why an otherwise social dog becomes aggressive on a leash. When strained, the leash pitches an otherwise passive body into a defensive pose. To another dog, this positioning sends an alert and causes defenses to go up. If this dog is also held by leash in a strangle hold, the tension only escalates.

What is the solution? Dogs must be taught to walk on a loose lead behind their people. In this position, they naturally take direction and don’t charge. (Happy Training, Happy Tails covers leash etiquette.)

Table 3-4 can help you decode the meaning behind every posture.

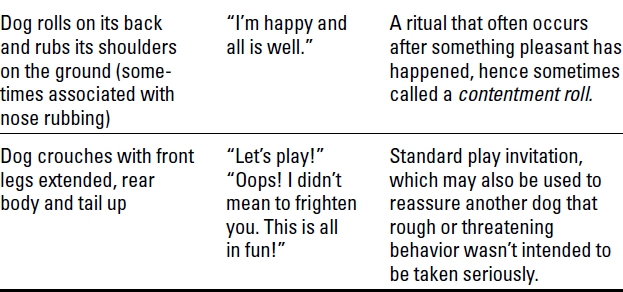

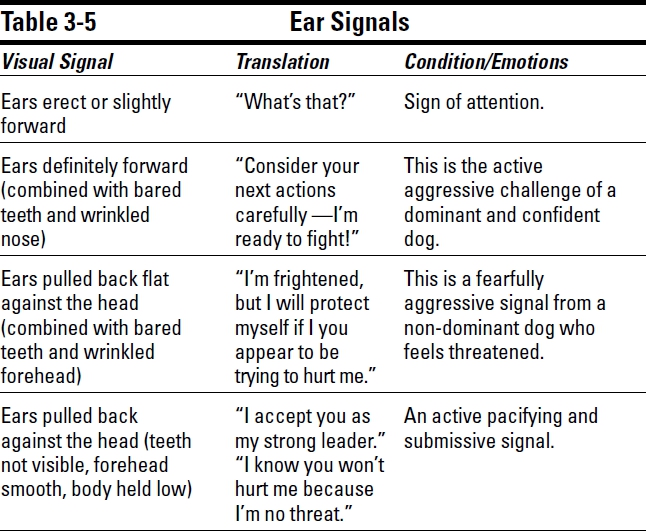

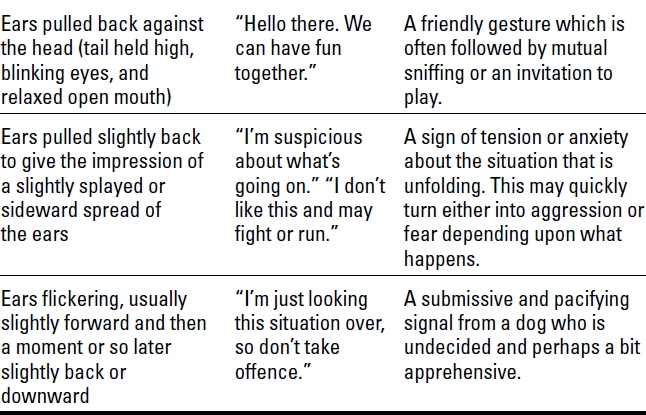

The ups and downs of the ears

Focus on your dog’s ears. Whether floppy or erect, their various poses provide insight into her focus and intention, especially when looked at in relation to other postures, positions, and vocalizations. Table 3-5 highlights the meaning behind the many ways dogs use their ears to communicate.

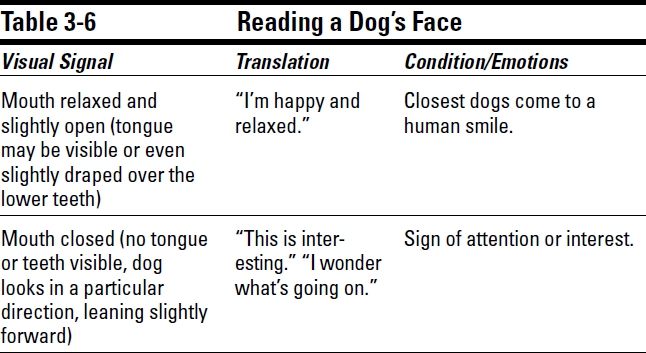

Facial signals

Though facial signals may vary slightly based on coinciding gestures or postures, Table 3-6 outlines the scope of emotions that can be predicted when the facial cues are watched.

TipAs a general rule, the more teeth that show when a dog is growling, the greater the threat. When a dog’s mouth is open, you should look at the shape of the opening: A “C” shape is dominant, whereas drawn lips, with the rear corners pulled back, gestures submission

or fear.

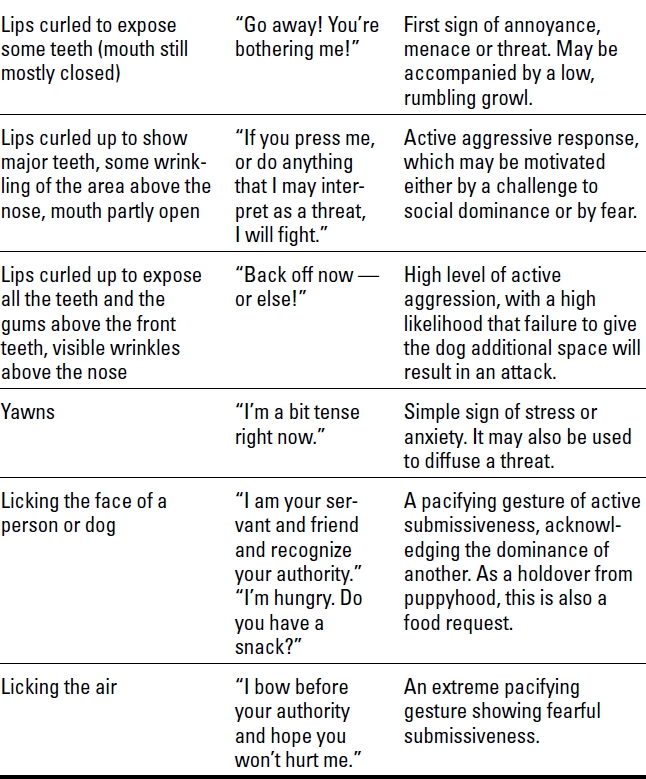

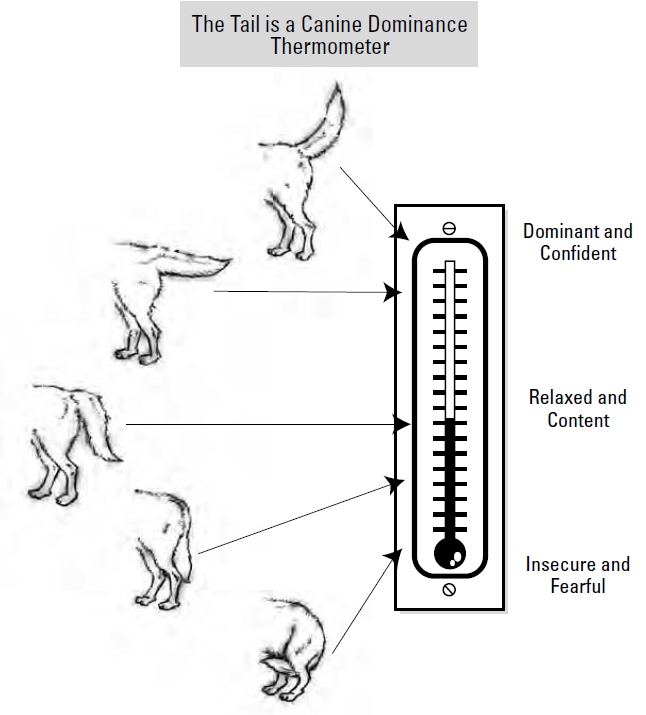

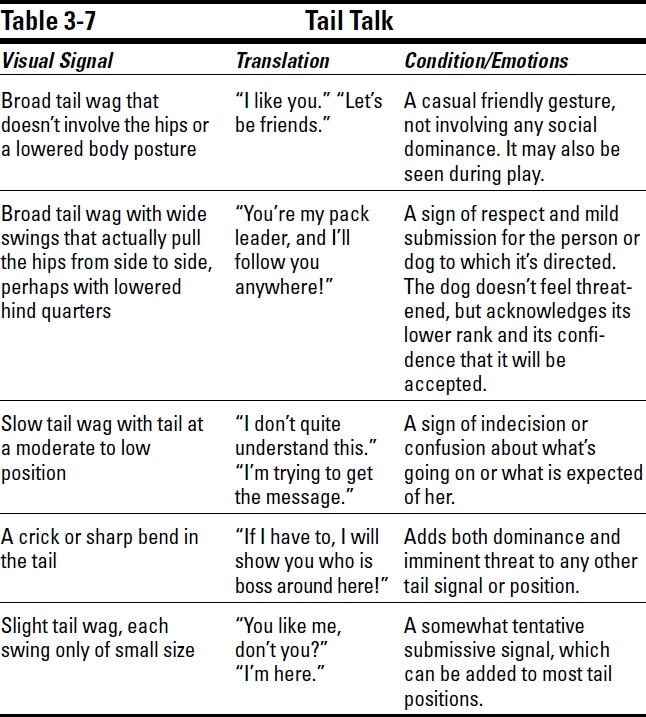

Tail talk

When reading your dog’s tail, you must interpret all motions based on her tail’s normal resting pose. A Greyhound, for example, carries her tail low when she’s relaxed, as compared to a Malamute, whose tail is upright and curled when she’s calm. With that said,

generally a higher tail indicates a dominant attitude, whereas a low tail communicates submission or fear (see Figure 3-4).

generally a higher tail indicates a dominant attitude, whereas a low tail communicates submission or fear (see Figure 3-4).

Figure 3-4: Common tail positions.

Also consider the rate of the wag, because faster motion evidences a higher level of arousal. The exception to this rule? A trembling tail, which actually looks as though it’s vibrating. This tail isn’t “wagging” so much as its signaling intense emotion and excitement.

Remember!A wagging tail doesn’t always invite interaction, nor is it always a gesture of good will. Dogs use their tails (see Table 3-7) in combination with the many other body signals outlined in this chapter to convey various “moods,” from pleasure to emotional agitation.

by Stanley Coren and Sarah Hodgson