In This Chapter

- Distinguishing your dog’s instinctive behaviors

- Knowing what drives your dog to certain behaviors

- Profiling your dog’s personality

- Applying your dog’s profile to your training plans

To train Buddy, you need some insight into what is happening at any given moment in his little brain. Here, your powers of observation can help you. In many instances, Buddy’s behavior is quite predictable based on what he has done in similar situations before. You may be surprised at what you already know. You can almost see the wheels turning when he’s about to chase a car, bicycle, or jogger. If you’re observant, Buddy will give you just enough time to stop him.

Recognizing Your Dog’s Instinctive Behaviors

Remember

Your dog and every other dog is an individual animal that comes into the world with a specific grouping of genetically inherited, predetermined behaviors. How those behaviors are arranged, their intensity, and how many components of each determine the dog’s temperament, personality, and suitability for the task required. Those behaviors also determine how the dog perceives the world.

Can dogs “reason”?As much as you would want your dog to be able to reason, the answer is no, not in the sense that humans can. Dogs can, however, solve simple problems. By observing your dog, you learn his problem-solving techniques. Just watch him try to open the cupboard where the dog biscuits are kept. Or see how he works at trying to retrieve his favorite toy from under the couch. During your training, you’ll also have the opportunity to see Buddy trying to work out what you’re teaching him. Our favorite story involves a very smart English Springer Spaniel who had been left on our doorstep. The poor fellow had been so neglected that we didn’t know he was a purebred Spaniel until after he paid a visit to the groomer. He became a delightful member of the family for many years. One day, his ball had rolled under the couch. He tried everything — looking under the couch, jumping on the backrest to look behind it, and going around to both sides. Nothing seemed to work. In disgust, he lifted his leg on the couch and walked away. So much for problem solving. |

- Prey

- Pack

- Defense

Prey drive

Remember

Prey drive includes those inherited behaviors associated with hunting, killing prey, and eating. The prey drive is activated by motion, sound, and smell. Behaviors associated with prey drive (see Figure 5-1) include the following:

- Air scenting and tracking

- Biting and killing

- Carrying

- Digging and burying

- Eating

- High-pitched barking

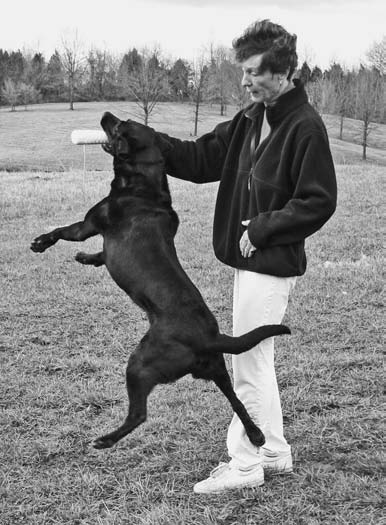

- Jumping up and pulling down

- Pouncing

- Seeing, hearing, and smelling

- Shaking an object

- Stalking and chasing

- Tearing and ripping apart

Pack drive

Remember

Pack drive consists of behaviors associated with reproduction, being part of a group or pack, and being able to live by the rules. Dogs, like their distant ancestors the wolves, are social animals. To hunt prey that’s mostly larger than themselves, wolves have to live in a pack. To assure order, they adhere to a social hierarchy governed by strict rules of behavior. In dogs, this translates into an ability to be part of a human group and means a willingness to work with people as part of a team.

– Being able to breed and to be a good parent

– Demonstrating behaviors associated with social interaction with people and other dogs, such as reading body language

– Demonstrating reproductive behaviors, such as licking, mounting, washing ears, and all courting gestures

– Exhibiting physical contact with people and/or other dogs

– Playing with people and/or other dogs

Defense drive

Remember

Defense drive is governed by survival and self-preservation and consists of both fight and flight behaviors. Defense drive is complex because the same stimulus that can make a dog aggressive (fight) can elicit avoidance (flight) behaviors, especially in a young dog.

- Disapproving of being petted or groomed

- Hackling up from the shoulder forward

- Growling at people or dogs when he feels his space is being violated

- Guarding food, toys, or territory against people and dogs

- Lying in front of doorways or cupboards and refusing to move

- Putting his head over another dog’s shoulder

- Standing tall, weight forward on front legs, tail high, and staring at other dogs

- Standing his ground and not moving

- Demonstrating a general lack of confidence

- Disliking being touched by strangers

- Flattening of the body with the tail tucked when greeted by people or other dogs

- Hackling that goes up the full length of the body, not just at the neck

- Hiding or running away from a new situation

- Urinating when being greeted by a stranger or the owner

Technical Stuff

Freezing — not going forward or backward — is interpreted as inhibited flight behavior.

Whoa! Buddy’s got his hackles upHackles refer to the fur along the dog’s spine from the neck to the tip of his tail. When a dog is frightened or unsure, the fur literally stands up and away from his spine. In a young dog, it may happen frequently because the dog’s life experiences are minimal. When he meets a new dog, for example, he may be unsure whether or not that dog is friendly, and so his hackles go up. His whiskers are also a good indication of his insecurity; they’re pulled back, flat along his face. His ears are pulled back, and his tail is tucked. And he cringes, lowering his body posture and averting his eyes. All in all, he’d rather be somewhere else. On the flip side, when the hackles go up only from the neck to the shoulders, the dog is sure of himself. He’s the boss, and he’s ready to take on all comers. His ears are erect, his whiskers are forward, all his weight is on his front legs, his tail is held high, and he stands tall and makes direct eye contact. He’s ready to rumble. |

How the drives affect training

Clearly, these generalizations don’t apply to every dog of a particular breed. Today, many dogs of different breeds were bred solely for appearance and without regard to function, so their original traits have become diluted.

Determining Your Dog’s Personality Profile

Remember

When completing the profile, keep in mind that we devised it for a house dog or pet with an enriched environment, perhaps even a little training, and not a dog tied out in the yard or kept solely in a kennel — such dogs have fewer opportunities to express as many behaviors as a house dog. Answers should indicate those behaviors Buddy would exhibit if he’d not already been trained to do otherwise. For example, did he jump on people to greet them or jump on the counter to steal food before he was trained not to do so?

- Almost always — 10

- Sometimes — 5 to 9

- Hardly ever — 0 to 4

1. Sniff the ground or air? _____

2. Get along with other dogs? _____

3. Stand his ground or show curiosity in strange objects or sounds? _____

4. Run away from new situations? _____

5. Get excited by moving objects, such as bikes or squirrels? _____

6. Get along with people? _____

7. Like to play tug-of-war games to win? _____

8. Hide behind you when he feels he can’t cope? _____

9. Stalk cats, other dogs, or things in the grass? _____

10. Bark when left alone? _____

11. Bark or growl in a deep tone of voice? _____

12. Act fearfully in unfamiliar situations? _____

13. Bark in a high-pitched voice when excited? _____

14. Solicit petting, or like to snuggle with you? _____

15. Guard his territory? _____

16. Tremble or whine when unsure? _____

17. Pounce on his toys? _____

18. Like to be groomed? _____

19. Guard his food or toys? _____

20. Cower or turn upside down when reprimanded? _____

21. Shake and “kill” his toys? _____

22. Seek eye contact with you? _____

23. Dislike being petted? _____

24. Act reluctant to come close to you when called? _____

25. Steal food or garbage? _____

26. Follow you around like a shadow? _____

27. Guard his owner(s)? _____

28. Have difficulty standing still when groomed? _____

29. Like to carry things in his mouth? _____

30. Play a lot with other dogs? _____

31. Dislike being groomed or petted? _____

32. Cower or cringe when a stranger bends over him? _____

33. Wolf down his food? _____

34. Jump up to greet people? _____

35. Like to fight other dogs? _____

36. Urinate during greeting behavior? _____

37. Like to dig and/or bury things? _____

38. Show reproductive behaviors, such as mounting other dogs? _____

39. Get picked on by older dogs when he was a young dog? _____

40. Tend to bite when cornered? _____

Table 5-1 Scoring the Profile | |||

Prey | Pack | Fight | Flight |

1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

5. | 5. | 7. | 8. |

9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

13. | 14. | 15. | 16. |

17. | 18. | 19. | 20. |

21. | 22. | 23. | 24. |

25. | 26. | 27. | 28. |

29. | 30. | 31. | 32. |

33. | 34. | 35. | 36. |

37. | 38. | 39. | 40. |

Total Prey | Total Pack | Total Fight | Total Flight |

Deciding How You Want Buddy to Act

- Come

- Down

- Sit

- Stay

- Walk on a loose leash

- Chase a cat

- Dig

- Follow the trail of a rabbit

- Retrieve a ball or stick

- Sniff the grass

- Chase bicycles, cars, children, or joggers

- Chase cats or other animals

- Chew your possessions

- Pull on the leash

- Roam from home

- Steal food

Remember

The beauty of the drives theory is that, if used correctly, it gives you the necessary insight to overcome areas where you and your dog are at odds with each other as to appropriate behavior. A soft command may be enough for one dog to change the undesired behavior, whereas a check is required for another.

Bringing out drives

– Prey drive is elicited by the use of motion — hand signals (except “Stay”) — a high-pitched tone of voice, the movement of an object of attraction (stick, ball, or food), chasing or being chased, and leaning or running backwards as your dog comes to you.

– Pack drive is elicited by calmly and quietly touching, praising and smiling, grooming, and playing and training with your body erect.

– Defense drive is elicited by a threatening body posture, such as leaning or hovering over the dog either from the front or the side, staring at the dog with direct eye contact (this is how people get bitten), leaning over and wagging a finger in the dog’s face while chastising him, checking the dog, using a harsh tone of voice, and exaggerating the use of the “Stay” hand signal (see Chapter Mastering Basic Training).

Switching drives

He’s playing with his favorite toy.

The doorbell rings; he drops the toy, starts to bark, and goes to the door.

You open the door; it’s a neighbor, and Buddy goes to greet him.

He returns to play with his toy.

Tip

The precise manner in which you get Buddy back into pack drive — you must go through defense — depends on the strength of his defense drive. If he has a large number of defense (fight) behaviors, you can give him a firm tug on the leash, which switches him out of prey into defense. To then get him into pack, touch him gently on the top of his head (don’t pat), smile at him, and tell him how clever he is. Then continue to work on your walking on a loose leash.

Remember

For the dog that has few fight behaviors and a large number of flight behaviors, a check on the leash is often counterproductive. Body postures, such as bending over the dog or even using a deep tone of voice, are usually enough to elicit defense drive. By his response to your training — cowering, rolling upside down, not wanting to come to you for the training session — your dog will show you when you overpower him, thereby making learning difficult, if not impossible.

– From prey into pack: You must go through defense.

How you put your dog into defense depends on the number of defense (fight) behaviors he has. As a general rule, the more defense (fight) behaviors the dog has, the firmer the check needs to be. As the dog learns, a barely audible voice communication or a slight change in body posture will suffice to encourage your dog to go from prey through defense into pack drive.

– From defense into pack: Gently touch or smile at your dog.

– From pack into prey: Use an object (such as food) or motion.

Remember

Applying the concept of drives, learning which drive Buddy has to be in and how to get him there speeds up your training process enormously. As you become aware of the impact your body stance and motions have on the drive he’s in, your messages will be perfectly clear to your dog. Your body language is congruent with what you’re trying to teach. Because Buddy is an astute observer of body motions, which is how dogs communicate with each other, he’ll understand exactly what you want.

Applying drives to your training

– Defense (fight) — more than 60: A firm hand doesn’t bother your dog much. Correct body posture isn’t critical, although incongruent postures on your part can slow down the training. Tone of voice should be firm, but pleasant and nonthreatening.

– Defense (flight) — more than 60: Your dog won’t respond to strong corrections. Correct body posture and a quiet, pleasant tone of voice are critical. Avoid using a harsh tone of voice and any hovering — either leaning over or toward your dog. There’s a premium on congruent body postures and gentle handling.

– Prey — more than 60. Your dog will respond well to a treat or toy during the teaching phase. A firm hand may be necessary, depending on strength of defense drive (fight), to suppress prey drive when in high gear, such as when chasing a cat or spotting a squirrel. This dog is easily motivated, but also easily distracted by motion or moving objects. Signals will mean more to this dog than commands. There’s a premium on using body, hands, and leash correctly so as not to confuse the dog.

– Prey — less than 60. Your dog probably isn’t easily motivated by food or other objects, but also isn’t easily distracted by or interested in chasing moving objects. Use praise to your advantage in training.

– Pack — more than 60. This dog responds readily to praise and physical affection. The dog likes to be with you and will respond with little guidance.

– Pack — less than 60. Start praying. Buddy probably doesn’t care whether he’s with you or not. He likes to do his own thing and isn’t easily motivated. Your only hope is to rely on prey drive in training. Limited pack drive is usually breed-specific for dogs bred to work independently of man.

Tip

If your dog is high in both prey and defense (fight), you may need professional help. He’s by no means a bad dog, but you may become exasperated with your lack of success. The dog may simply be too much for you to train on your own. (See Chapter Seeking Expert Outside Help for advice on finding help.)

– If your dog is high in defense (fight), you need to work especially diligently on your leadership exercises and review them frequently (see Chapter Setting the Stage for Training).

– If your dog is high in prey, you also need to work on these leadership exercises to control him around doorways, moving objects, and similar distractions.

– If your dog is high in both prey and defense (fight), you may need professional help with your training.

– The Couch Potato — low prey, low pack, low defense (fight): This dog is difficult to motivate and probably doesn’t need extensive training. He needs extra patience if training is attempted because he has few behaviors with which to work. On the plus side, this dog is unlikely to get into trouble, doesn’t disturb anyone, makes a good family pet, and doesn’t mind being left alone for considerable periods of time.

– The Hunter — high prey, low pack, low defense (flight): This dog gives the appearance of having an extremely short attention span but is perfectly able to concentrate on what he finds interesting. Training requires the channeling of his energy to get him to do what you want. You need patience, because you have to teach the dog through prey drive.

– The Gas Station Dog — high prey, low pack, high defense (fight): This dog is independent and not easy to live with as a pet. Highly excitable by movement, he may attack anything that comes within range. He doesn’t care much about people or dogs and works well as a guard dog. Pack exercises, such as walking on a leash without pulling, need to be built up through his prey drive. This dog is a real challenge.

– The Runner — high prey, low pack, high defense (flight): Easily startled and/or frightened, this dog needs quiet and reassuring handling. A dog with this profile isn’t a good choice for children.

– The Shadow — low prey, high pack, and low defense (fight): This dog follows you around all day and is unlikely to get into trouble. He likes to be with you and isn’t interested in chasing much of anything.

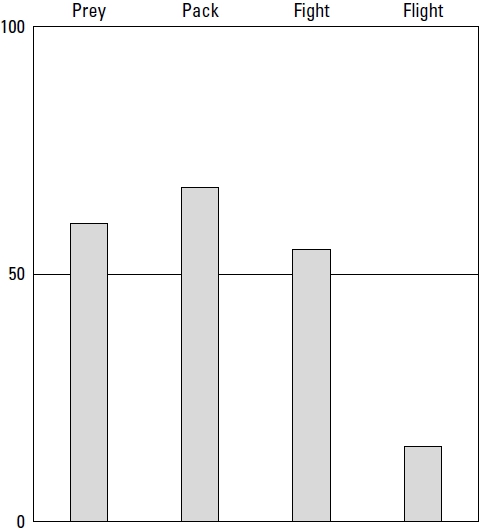

– Teacher’s Pet — medium (50 to 75) prey, pack, and defense (fight): This dog is easy to train and motivate, and mistakes on your part aren’t critical. Teacher’s Pet has a nice balance of drives. He’s easily motivated and therefore quite easy to train — even when your training skills aren’t particularly keen. At our training camps and seminars, we have the owners put the profile of their dogs in graph form for easy reading. Figure 5-4 shows the graph for Teacher’s Pet.