In This Chapter

- Knowing how much protein, carbohydrates, and fats your dog needs

- Making sure that your dog is getting the right amount of vitamins and minerals

- Getting an inside look at how your dog’s food is made

- Checking out organic options

Proteins

Technical Stuff

Proteins are made up of amino acids linked in a chain. When your dog eats protein, enzymes that the pancreas secretes into the intestines break them down into shorter chains of amino acids called polypeptides, which are small enough for the intestines to absorb. A dog’s body makes 20 different amino acids — some are essential amino acids and others are nonessential amino acids. As the name implies, your dog requires essential amino acids in his food. Food that contains all the essential amino acids is called a complete protein source. The nonessential amino acids are . . . drum roll, please . . . not essential; if your dog doesn’t get them in his diet, he can convert other amino acids into those that he’s missing.

Remember

Your dog’s major source of protein should be animal products, not grain. Don’t buy a dog food in which soybean meal, soy flour, or corn gluten meal is the primary, or even the secondary, source of protein (see the section “Reading a Dog Food Label” later in this chapter for more on this). Dogs don’t have the enzymes to use grains properly as main sources of protein.

Tip

The American Association of Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) is the organization that sets guidelines for the types and amounts of nutrients dogs need in their foods. The AAFCO has determined that foods for adult dogs should contain no less than 18 percent protein, and that foods for lactating females or puppies should have a minimum of 22 percent protein. Military or police dogs, mushing dogs, and other dogs who work hard every day or who are under stress may need more. Dogs recuperating from injuries or surgery may need more protein as well, to repair muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

Technical Stuff

Not all complete protein sources are created equal. A cow’s hoof and a filet mignon may both have all the essential and nonessential amino acids, but your dog can get the amino acids he needs more easily from the filet mignon than from the cow’s hoof. Some proteins are just more digestible than others. So how do we know which protein sources are digestible and which aren’t? Nutritionists measure the amount of protein in a food, feed it to dogs, and then measure the amount of protein in the dogs’ feces. The difference between how much was in the food to begin with and how much the dog excretes reveals how much of it the dog absorbed, and that is the digestible protein. A protein isn’t very useful to your dog if it ends up on your lawnrather than in his body. Hair and feathers are a cheap source of protein, too — but they’re indigestible. On the other hand, eggs are highly digestible but expensive. Not surprisingly, the more digestible the protein, the more expensive the dog food. As with many things in life, you get what you pay for.

Warning!

Beware of foods that advertise over 90 percent digestibility. The highest-quality dog foods are 82–86 percent digestible, whereas economy foods (inexpensive brands you get in grocery stores) are around 75 percent. The percent digestibility of a dog food is not stated on the label, but most dog food manufacturers provide that information on request.

Tip

If your dog’s feces are voluminous, it may be a sign that his food isn’t highly digestible.

A brief history of dog food | |

Before the late 19th century, there was no such thing as prepared dog food. Lucky dogs owned by the well-to-do ate the leftovers from their owners’ dinners, and street dogs aplenty canvassed the alleys, scrounging in the trash. In the 1870s, a time when transportation literally used horse power, a European entrepreneur devised a unique way to solve the problem of what to do with the carcasses of the many horses that died every day in the cities: He decided to package and sell the horse meat as dog food. The idea caught on, particularly among the wealthy, who appreciated the convenience of having a ready-made food for their dogs. The first commercial dog foods in North America were made by Ralston-Purina in 1926. The foods were tested on dogs that the company kept in large kennels on the property near St. Louis, Missouri. Ralston-Purina dog food was given the ultimate test when it was fed to the sled dogs on Admiral Byrd’s expedition to Antarctica in 1933. Although this was a punishing test for a dog food, it also was an early precursor to the celebrity endorsements that are a major part of the advertising budgets for many large companies today. In the decade after World War II, the idea of prepared dog food really caught on. The economy was booming and people didn’t mind spending a little money for the convenience of having a ready-made dog food for their canine companions. Besides, the companies producing these dog foods were performing studies on the nutritional needs of dogs, and their foods were billed as containing everything a healthy dog needed. At that time, most dog foods were canned. This method of preserving food was familiar to Americans, who enjoyed the convenience of canned human foods that could be stored for months or even years on their shelves. In | 1956, dog food companies began to utilize the extrusion process, in which nutrients in dried form are mixed with water and steam- and pressure-forced through an opening; the extruded material then is cut into small pieces. The food pieces are cooled, coated with vitamins and other components that are lost in the process of heating, flavored, and packaged. Dry dog food allowed the consumer to more easily carry large amounts of dog food home from the grocery store. In addition, people found pouring food from a bag more convenient than opening a metal can. Plus, dry foods were advertised as helping keep dogs’ teeth cleaner. As a result, since the late 1960s, the majority of dogs have been fed dry dog food, although canned food is still widely used, especially for smaller dogs. In the early 1970s, the National Research Council (NRC) published the first recommendations listing the minimal nutritional requirements of dogs. Dog food companies now had a standard by which they could measure the nutritional value of their foods and parameters by which they could claim their foods to be complete and balanced. (The term complete indicated that all the required nutrients were present in their foods, and balanced indicated that these nutrients were in the correct proportions.) The NRC nutrient requirements for dog foods were supplanted in 1992 by nutrient profiles established by the American Association of Feed Control Officials (AAFCO). Throughout the late 20th century, as the dog population continued to grow, so did the dog food industry. By 1999, the pet food industry was an $11-billion-a-year industry — and very competitive. Today dog foods are advertised and marketed every bit as competitively as human foods, highlighting the importance of being aware of what you’re buying. |

Fats

Tip

The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids is listed on the bags of some of the better-quality foods, so if your dog is having skin problems, opt for a higher-quality food — and one with the correct ratio of omega-6 to omega-3.

Tip

Be sure to read the dog food label before choosing a diet for your dog and observe your dog’s response to the food. If you don’t like the appearance of your dog’s coat and skin on one diet, try a different one.

Carbohydrates

Technical Stuff

Carbohydrates come in three basic forms: sugars, starches, and cellulose. Sugars and starches are simple carbohydrates because they are readily available as glucose or can be broken down into glucose. Good sources of simple carbohydrates are rice, oatmeal, corn, and wheat. Simple carbohydrates are easy for your dog to digest when properly cooked; they also add texture to the food, making it more palatable. Cellulose, the main carbohydrate found in the stems and leaves of plants, is a complex carbohydrate. Dogs don’t have the enzymes to digest cellulose (most animals don’t), but it serves as fiber, helping regulate water in the large intestine and aiding formation and elimination of feces.

Tip

The best foods use the carbohydrates that come in grains; sugar need not be added to food, although some manufacturers do this to make it taste better. The AAFCO has no recommended minimum or maximum levels of carbohydrates in dog foods. Carbs make up the remainder of the bulk of the food after fats, proteins, fiber, and vitamins and minerals have been added.

Fiber

Water

Remember

Every dog should have access to clean, fresh water at all times.

Enzymes

Vitamins

Water-soluble vitamins

– Thiamin (vitamin B1): Promotes a good appetite and normal growth. Required for energy production.

– Riboflavin (vitamin B2): Promotes growth.

– Pyridoxine (vitamin B6): Aids in the metabolism of proteins and the formation of red blood cells.

– Pantothenic acid: Required for energy and for protein metabolism.

– Niacin: Exists in many enzymes that process carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

– Vitamin B12: Necessary for DNA synthesis and intestinal function.

– Folic acid: Works together with vitamin B12 and in many of the body’s chemical reactions.

– Biotin: Acts as a component of several important enzyme systems.

– Choline: Required for proper transmission of nerve impulses and for utilization of sulfur-containing amino acids.

– Vitamin C: Participates in the formation of bones, teeth, and soft tissue.

Fat-soluble vitamins

– Vitamin A: Necessary for proper vision, especially night vision. Important in bone growth, reproduction, and maintenance of tissues such as the lungs, intestines, and skin.

– Vitamin D: Critical to the dog’s ability to use calcium and phosphorus for bone and cartilage growth and maintenance.

– Vitamin E: An antioxidant that protects the cells (and dog food) from oxidative damage. Important for muscular and reproductive function.

– Vitamin K: Essential for normal blood clotting.

Minerals

Warning!

Your dog’s body needs to maintain a delicate balance between the various major and trace minerals. For several trace minerals, the line between the required amount and toxic levels is a thin one. So supplementing an already balanced dog food with minerals can create more problems than it solves.

Table 1-1 Sources of Minerals | |

Mineral | Source |

Calcium | Dairy products, poultry, meat bone |

Phosphorus | Meat, poultry, fish |

Magnesium | Soybeans, corn, cereal grains, bone meals |

Sulfur | Meat, poultry, fish |

Iron | Organ meats |

Copper | Organ meats |

Zinc | Beef liver, dark poultry meat, milk, egg yolks, legumes |

Manganese | Meat, poultry, fish |

Iodine | Fish, beef, liver |

Selenium | Grains, meat, poultry |

Cobalt | Fish, dairy products |

Major minerals

Technical Stuff

Although the ratio of calcium to phosphorus in a dog food is important, the total amount of calcium ingested may be more important. Excess calcium is thought to contribute to the development of hip and elbow dysplasia, osteochondrosis dissecans (degeneration of the joint cartilage), and other bone and joint problems. Calcium deficiencies frequently occur in dogs who are fed all-meat diets. A severe deficiency of calcium can cause rickets and bone malformations. A moderate deficiency can cause muscle cramps, impaired growth, and joint pain.

Tip

As of this writing, all premium-quality adult maintenance dog foods produced by major manufacturers have enough calcium to support the healthy growth of puppies, including those of giant breeds. Resist the urge to provide extra supplementation of vitamins and minerals, particularly those containing calcium, to your growing puppy on a premium dog food.

Warning!

Never add bone meal to a complete and balanced diet. Not only are you likely to alter the critical calcium to phosphorus ratio, but you also risk decreasing your dog’s ability to absorb and utilize many of the other minerals he needs.

Trace minerals

– Iron: Iron is present in every cell in the body. It is particularly important, along with protein and copper, for the production of red blood cells, which are responsible for transporting oxygen from the lungs to every part of the body. Dogs with iron deficiency develop anemia. But remember, iron is needed in only small amounts, so it is important that you not supplement with iron unless you have a prescription.

– Zinc: Zinc is important in the metabolism of several vitamins, particularly the B vitamins. It is also a component of several enzymes needed for digestion and metabolism, and it promotes healing as well. Your dog needs zinc for proper coat health. Some breeds of dogs, particularly the northern breeds such as Siberian Huskies, appear to have problems with absorption and/or utilization of zinc. These dogs develop poor coats and dry, scaly skin with sores (particularly on the nose and mouth) and stiff joints unless they are supplemented with zinc.

– Copper: Copper is a trace mineral that has many different functions. It is needed for the production of blood and for the proper absorption of iron. It is also involved in the production of connective tissue (the cells and extracellular proteins that form the background structure of most tissues) and in healing. Copper is found in fish, liver, and various grains. The amount of copper in a grain is related to the level of copper in the soil where the grain was grown. A copper deficiency can result in anemia and skeletal abnormalities. Some breeds of dogs, such as Bedlington Terriers and Doberman Pinschers, can have a genetic problem that interferes with the metabolism of copper. In these dogs, copper is stored in the liver to toxic levels, resulting in hepatitis.

– Iodine: Iodine is critical for the proper functioning of the thyroid gland, which regulates the body’s metabolism and energy levels and promotes growth. Iodine is found in high levels in fish. It is added to most dog foods to make the levels sufficient for canine health.

– Selenium: Selenium works with vitamin E to prevent oxidative damage to cells. It is needed in only minute amounts in the diet. Meats and cereal grains are good sources of selenium. In dogs, an excess of selenium results in death of the heart muscles, as well as damage to the liver and kidney. Deficiency results in degeneration of heart and skeletal muscles.

– Manganese: Manganese is a component of many different enzyme systems in the body. Most important, it activates enzymes that regulate nutrient metabolism. It is found in legumes and whole-grain cereals; animal-based ingredients are not a good source of manganese.

– Cobalt: Cobalt is a part of vitamin B12, which is an essential vitamin. Cobalt does not appear to have any function independent of vitamin B12.

Remember

As scientists discover more about the nutritional needs of dogs, they are beginning to recognize that our canine companions may need different nutrient levels for optimal health than they need just to prevent deficiencies. Be sure to discuss nutritional questions with your veterinarian — and take a vet’s advice over anyone selling dog food, because stores may push the brands that give them a bigger profit margin. And if you have a question about a specific dog food, call the manufacturer.

Technical Stuff

How dog food is made | |

How do some cows or chickens and a pile of grains turn into your dog’s dinner? First the animals are slaughtered and the body parts not used for human consumption are put into bins according to which parts of the body they do or do not contain. These are either shipped directly to the dog food manufacturer or are rendered and the meal (what remains after the fats are removed) is shipped to the manufacturer. Similarly, either grains or the meal (what remains after the oils have been extracted for use in human foods) may be shipped to the dog food manufacturer. If whole grains are sent, the manufacturer grinds and separates the grains into their different components. For example, wheat may be separated into wheat flour, wheat germ meal, wheat bran, and wheat middlings. The ingredients are then mixed in proper proportions and added to the extruder, a large tube containing a screw that mixes the ingredients with steam and water under pressure, and then squirts out the mixture through holes at the end, like a pasta maker squeezes out spaghetti. A knife cuts the ribbon into small pieces, which are then moved along a conveyor belt through a | dryer/cooler until the right amount of moisture remains. The food is then coated with fat, vitamins, and flavorings. The high temperature at which dry dog foods are processed breaks down proteins and may change their structure and quality. In addition, the heat destroys any enzymes that were in the food components. Vitamins that have been destroyed during processing have to be sprayed back onto the food after it cools. But whether the components that are added back are really the same as those that were present in the unprocessed food components is unclear, and this is why some people prepare foods for their dogs at home. As a trade-off, however, processed dog food is virtually sterile. None of the common bacteria present on beef and poultry, such as salmonella and E. coli, remain after the food is processed. Semi-moist foods are not dried as much, and they have more preservatives and sugar added. Canned dog foods are heated but not sent through an extruder. Thus, they tend to retain more of the natural proteins, fats, vitamins, and enzymes. |

The Main Types of Dog Food

Warning!

Most veterinary nutritionists agree that semi-moist dog foods offer very little nutritional value. These foods contain dyes and other nonessential additives so that they can be shaped into little bones, steaks, or other shapes. The additives may make the food visually appealing to the consumer, but dogs don’t care what their food looks like. Semi-moist foods also are preserved with sugar, which contributes to obesity and periodontal disease in dogs.

Tip

Avoid foods that don’t have complete nutritional information on the label (see the “Reading a Dog Food Label” section of this chapter for more information). Foods that are produced and sold within the same state aren’t required to have complete nutritional information the way foods that are sold across state lines are. These foods may be nutritionally sound, but without complete information, you can’t be sure. Also steer clear of dog foods that haven’t been tested in feeding trials with real live dogs.

Who’s in charge around here?Several watchdog groups oversee various parts of the dog food manufacturing and marketing process. Take a look at this rundown of the regulatory agencies and what they do:

|

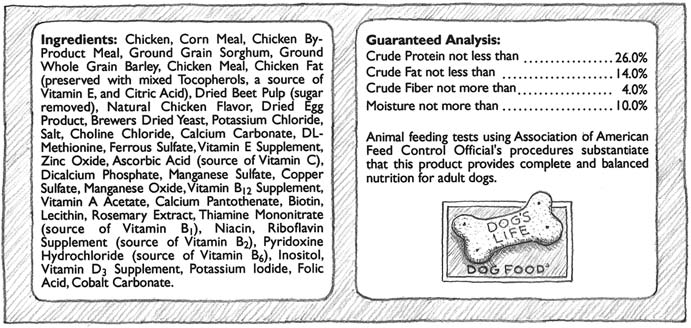

Reading a Dog Food Label

The first place you need to look when trying to decide on a food for your furry friend is the label on the bag, box, or can. Reading a dog food label isn’t very different from reading the one on your cereal box. A certain amount of nutritional information must be included on the label, but a certain amount of leeway exists in how the dog food company presents it.

The product display panel

Product identity

Technical Stuff

Any terminology regarding the meat or meat flavor used in the product identity statement has to comply with a list of specific definitions. Consider some examples of common phrases and the standards that need to be met before the dog food company can use the phrase:

– Beef for dogs: The food must contain 95 percent beef by weight.

– Beef dog food: The food must contain 70 percent beef by weight.

– Beef dinner, beef entrée, or beef platter: The food must contain 25 percent beef by weight.

– Dog food with beef: The food needs to contain only 3 percent beef.

– Beef-flavored: The food doesn’t need to contain any beef; it just needs to taste like beef (using artificial flavors).

Tip

The same rules for terminology apply to any meat source in dog food, such as chicken, lamb, and so on.

Product use

Net weight

Warning!

The product display panel includes the net weight of the package contents. Just as with human foods, dog food manufacturers frequently change the size of containers without changing the price. For example, a can that looks to be a standard 6-ounce size may actually contain 5.5 ounces, but at the same price. Be sure to read the label carefully.

Banner statement

The information panel

Guaranteed analysis

Tip

If your dog is ill, small differences in the amount of these important nutrients may make a difference in her health. If you have any questions about your dog’s food and whether you’re giving her what she needs, talk with your vet.

Tip

To make accurate comparisons between two foods, you need to do some math, so get out your calculator and follow these steps (protein is the example, but you can do the same equation for other nutrients as well):

Tip

If all this math seems to be more trouble than it’s worth, here’s a quick rule of thumb to help you compare dry and canned foods. For a dry food, to determine the level of protein, fat, or fiber on a dry-weight basis, add 10 percent to the level that is listed on the label. For a canned food, multiply the amount of protein, fat, or fiber by four. This timesaving tip makes it easier to compare while you’re standing in the store aisle.

Technical Stuff

As this exercise shows, canned foods typically have much more protein than dry foods. A major reason for this is that grains are needed in dry foods to help them hold their shape after extrusion. Canned and dry foods made by the same manufacturer usually have very different percentages of protein.

Ingredients list

Tip

In general, a good-quality dog food has two quality animal protein sources listed in the first few ingredients. Look for a food that also has two different sources of fat in the ingredients list, for adequate energy and to provide all essential fatty acids (see earlier in this chapter for more on fats).

Tip

Dog food companies frequently change the composition of their dog foods, so the label on the food you purchased yesterday may not be the same today. Keep the ingredients list from your current dog food label in your wallet and periodically check it against the labels on the dog foods you’re buying, just to make sure that you’re buying what you thought you were.

Tip

Vocabulary 101If you’re confused by some of the lingo on dog food bags, you’re not alone. Some of the definitions for the food terms you’ll see in the ingredients list include the following:

|

Preservatives and antioxidants in your dog’s foodAntioxidants are preservatives that are added to foods to help protect the fats, oils, and fat-soluble compounds such as vitamins from breaking down. Unsaturated fats readily mix with oxygen in the air and become rancid. Rancid fats are not just a problem because they smell bad; they also cause the food to lose its flavor and texture. More important, rancid fats can affect a dog’s health. When a dog eats rancid fats, he may end up suffering from a relative deficiency of vitamin E, a natural antioxidant that the body uses to combat rancid fat. Because all dog foods contain some unsaturated fats, they all require some sort of antioxidant preservative. Many foods are preserved with preservatives, including BHA, BHT, and ethoxyquin. Ethoxyquin has been especially controversial, because concerns arose that it caused cancer. However, studies in dogs and puppies have not shown an increase in cancer from ethoxyquin. Still, due to consumer preferences for natural ingredients, most dog foods are now preserved with vitamin E and vitamin C. Ironically, the vitamin E and vitamin C that are used in dog food are man made, too — so they’re not exactly “natural.” If you’re feeding a dog food that has been preserved with vitamins E and C, be sure that the food is less than six months old when you give it to your dog. Most manufacturers use a production code that indicates the date and even time when the food was made, along with the plant that manufactured it. Others use a best used by code, which indicates the time by which the food should be consumed. To determine how fresh your dog’s food is, call the manufacturer and ask them to explain their code. They will tell you what each number and letter means. Finally, a food’s antioxidant powers are depleted more rapidly during hot, humid weather, so in the warm summer months, use food that is less than six months old. Always store your dog’s food in a cool, dry place, and don’t buy more than a month’s supply at a time. |

Nutritional adequacy statement

Warning!

Dog food manufacturers can also sell dog foods that have been formulated according to the AAFCO nutritional profiles for dogs but have not been tested on dogs in feeding trials. To make a formulated food, the manufacturer adds an amount of protein that is at least 18 percent for adult dogs, an amount of fat that is at least 5 percent for adult dogs, and the required amounts of all the other required nutrients. If you feed your dog a food that has been formulated but not tested on dogs, your dog essentially becomes the test subject. Examples abound of formulated dog foods that looked good on paper but, when fed to dogs, resulted in nutritional deficiencies. Stay away from foods that have not been tested in dogs.

Technical Stuff

However, the regulations regarding feeding trials for dogs have a loophole. After a dog food manufacturer has proven by feeding trials that a given food is nutritionally adequate, the manufacturer may state that formulated foods have been tested by feeding trials, as long as the formulated foods are in the same family. Unfortunately, no guidelines spell out the definition of a family of dog foods. We are left to trust the manufacturer’s word.

Feeding guidelines

Manufacturer’s contact information

Tip

The customer service departments of dog food manufacturers are usually very helpful. If they don’t know the answer to a question, they will hunt it down and call you back. If you call a company and they can’t or won’t provide the information that you need, don’t feed that food to your dog.

Figuring Out How Much to Feed Your Dog

Tip

If the label doesn’t provide information on the caloric content of the food, you have to use the manufacturer’s recommendations as a starting point. Start by feeding 25 percent less than the manufacturer recommends and then increase or decrease the amount as necessary.

Table 1-2 Caloric Requirements of Dogs | |||

Caloric Requirements (Based on Activity Level)1 | |||

Dog’s Weight (In Pounds) | Inactive | Moderately Active | Highly Active |

10 | 234 | 303 | 441 |

20 | 373 | 483 | 702 |

30 | 489 | 633 | 921 |

40 | 593 | 768 | 1117 |

50 | 689 | 892 | 1297 |

60 | 779 | 1008 | 1466 |

70 | 863 | 1117 | 1625 |

80 | 944 | 1222 | 1777 |

90 | 1022 | 1322 | 1923 |

100 | 1097 | 1419 | 2064 |

Remember

The figures in Table 1-2 include treats and snacks.

Technical Stuff

As dogs exercise more, they need more calories to maintain their weight. But as dogs get larger, they require relatively fewer calories to maintain their weight. This is because larger dogs generally have slower metabolisms than smaller dogs. Age can affect caloric requirements, too. As a dog goes from 1 to 7 years of age, her energy requirements drop by an incredible 24 percent.

Remember

Dogs’ metabolisms vary so greatly that the best way to know exactly how many calories your dog needs each day is by trial and error. Feed the amount of food that will maintain your dog’s weight. If she loses weight, feed more. If she gains, feed less.

Choosing the Best Food for Your Dog

Remember

Sorry, but the best-quality foods are not the cheapest. However, the reverse isn’t necessarily true: Paying a lot for your dog food doesn’t guarantee its quality. As you search for the best food, don’t hesitate to experiment. Be a good observer. Talk to your veterinarian and other dog people, such as your breeder. Over time, you will gather more information and be able to make better decisions based on fact as well as experience.

Tip

When you have selected a quality food for your furry friend, your job isn’t done. You still need to keep close track of your dog’s response to the food. Watch his body condition. Your canine companion should maintain a correct weight on his new food. If he gains some weight but looks and acts healthy and full of energy, it may be that the nutrients in the new food are more digestible than those of the previous food, so you don’t need to feed as much. If your dog loses weight on his new food, start looking for another. Your dog’s coat should grow and glisten on his new food, and his skin should be pink and supple, with no sores. A dog’s coat is often a reflection of his general health, although it isn’t the only monitor to use. For example, during the spring in temperate climates, most dogs’ coats look dry as they shed their heavy winter garb for a lighter spring coat.

Tip

One of the best criteria you can use to monitor your dog on a new food is to observe his stools. Stool quality is determined by the ingredients in the food, the relative amounts of different ingredients, the type and amount of fiber, and the digestibility of the ingredients. Small, firm stools indicate a food that is highly digestible. However, your dog should not be constipated or straining to defecate. Large stools, particularly if they are somewhat loose, may indicate a food with less digestible nutrients and/or a high fiber content. Your dog’s stools will vary from day to day. But if your dog often has small, hard stools, consider changing to another food. Those stools may be easy to pick up, but they may also mean that your dog is chronically constipated.

Tip

Monitor your dog’s attitude and energy level. If you feed your dog a good-quality food, he will have lots of get-up-and-go. He will have the energy and endurance to play all you want. Most of all, he will have that joy for life that we all appreciate in our canine companions.

Paying Attention to How You Feed Your Dog

– Dogs who are free-fed are more likely to be overweight. This may not have been true in the past, but with today’s highly palatable foods, your dog will enjoy eating long past the point at which she’s full. She will likely take in more calories than she needs and carry the fat to prove it.

– You can’t tell exactly how much your dog is eating. In fact, you may not recognize that your dog is ill until you suddenly notice you haven’t been adding much food to her bowl in the past few days. Food intake is one of the best indicators of health, so you should always be in a position to monitor your dog’s intake accurately.

– Medicating dogs who are free-fed is more difficult. If you have to give your dog pills, such as heartworm preventive, and your dog is free-fed, you will have to make sure that you pop it down her throat and she swallows it. However, if she gets fed two square meals a day, you can just add the pill to her food and it will go right down the hatch!

– Free-feeding is difficult in multidog households. Frequently, one dog hogs the food and gains weight, while the other dog is deprived of the food and loses weight. Plus, free-feeding is impossible if your dogs require different kinds of food.

Tip

So how many times a day should you feed your dog? Feed puppies four times a day until they are 3 months of age, when you can move them to feedings three times a day. At 6 months of age, dogs can be fed twice a day, and this is probably the best feeding schedule for a dog to stay on for life. Some dogs are fed just once a day and get along fine. Occasionally, however, dogs who are fed once a day vomit a little fluid or bile 12 to 18 hours after their last meal. If they are fed twice a day, this problem goes away.

Remember

No two dogs are exactly the same. They have different metabolic rates, they have different metabolisms, and they may need to eat different diets. If you have more than one dog, it may be more convenient to feed all your dogs the same food, but make sure that you monitor each dog’s response to the diet you are feeding and change the food if an individual dog needs it.

Tip

Give your dog a quiet place to eat. If other dogs live in the house, don’t feed them from the same bowl. Feed them at a distance from each other so they don’t feel threatened that the other dog will steal their food. The best solution is to feed your dog in a crate so she can enjoy his meal in the privacy of her den. When you put the bowl down, give your dog 15 minutes to eat. If she hasn’t finished in that time, either you are feeding her too much or she isn’t motivated to eat. By removing the bowl, you can be assured that she will be much more motivated to eat at the next meal. Don’t be held hostage by a picky dog. If you try to encourage her to eat by talking nicely to her and giving her delectable treats, she will soon up the ante, demanding better and better treats until she’s not consuming her dog food at all.

Technical Stuff

Many veterinary nutritionists believe that we should be rotating our dogs’ diets — feeding them one food for three to six months, and then switching to another diet. They theorize that abnormal proteins may be formed during the processing of food or that individual foods may have undetectable deficiencies or small differences in the availability of certain nutrients. By rotating your dog to a new food every three to six months, you prevent too much exposure to the abnormality in any given food.

People food is okay in small amountsGiving your dog fresh vegetables and even some fresh fruit on a regular basis is a good idea. Wolves (from which our dogs are descended) eat the greens and grains from their prey’s stomach, and also eat grasses and berries at times. Dogs enjoy fresh vegetables and benefit from the vitamins and fiber they provide. The only vegetable to stay away from is raw onions (some say cooked onions are fine, but some say they aren’t). Feed your dog the leftovers from your preparations for dinner, in addition to other vegetables, especially the meats and vegetables. That way, both you and your dog benefit. Just make sure that vegetables aren’t the major component of your dog’s food. If you give the vegetables in large pieces, they provide mostly fiber because dogs don’t have the enzymes to digest cellulose, the major component of the cell walls of plants. However, if you put the vegetables through a juicer or a super-blender that breaks down the cell walls and turns the vegetables to mush, your dog will also benefit from the nutritional content of the vegetable. |

Organic Options for Feeding Your Dog

Food for thought: Organic versus naturalDeciphering food labels can feel like a chore, but it’s a chore worth doing when you’re serious about good health. A particularly confusing labeling distinction — and one that applies to food for humans and canines alike — is the one between organic and natural. Don’t be misled — organic and natural are not the same. Organic foods must be certified as organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture — that is, produced and processed without chemical pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, hormones, and antibiotics. Although natural foods are free of food coloring and chemical additives, they are not organic. So although natural foods have some benefits, they are not held to the same higher standard as organic foods. |

– Is produced without chemicals, steroids, or artificial colors and flavors.

– Contains better grades of grains and proteins to help with digestive issues such as gas or diarrhea.

– Has no bulk fillers, making food easier to digest. It may also help manage weight.

– May help with allergies and skin ailments.

– May help boost immunity, helping your dog ward off ailments.

– Isn’t as widely distributed as conventional dog food.

– Is more expensive than nonorganic dog food. (The same situation is true of organic food for humans.)

– Has not been proven through scientific evidence to help your dog live a longer or healthier life.