- Sorting out matches, trials, and classes

- Getting ready to go — at home and on the course

- Showtime: Making your run

While no one has to enter trials or earn titles to enjoy the sport of agility, if you stick with it and get pretty good at it, you just might find yourself daydreaming about a timed run and ribbons adorning your walls. I’ve been to many agility events. They’re a blast, whether you’re a spectator or a participant. Search for one in your area and spend a day there. If you’re anything like me, you’ll be shouting, cheering, and whooping in no time. Wear your best jumping-up-and-down shoes, and expect to go home hoarse.

Competition is 10 percent hype and 90 percent concentration. Most people get a few butterflies on judgment day, but your dog will be oblivious to what’s going on. Think of competitions as social gatherings where you meet people who share similar interests. Cop a breezy attitude as you wait your turn, then focus on the task at hand as though you were running the sequence in your backyard or on a practice field. Confidence is catching — the less you worry, the more comfortable and eager your dog will be on-course.

Remember that the only difference between you and your competitors is experience: Once you learn the ropes, it will be your turn to reach back and guide a newbie. For now, gratefully look to others for help.

In this chapter you find what you need to know about agility events, from the difference between match and trial competitions to how to register and prepare yourself. Though no one will say you must participate, don’t be surprised if you get drawn in!

Remember

You can’t fool your dog! If your nerves get the better of you as you prepare for competition, your dog will attribute it to the circumstances at hand. She may grow so concerned about you that she wouldn’t dream of leaving your side to concentrate on her performance.

Entering Agility Events

Once you feel confident sequencing and completing an agility course, you may feel drawn to competition, earning titles, and going to weekend events. Let me forewarn you: The first steps can seem a little confusing. There are match trials — kind of like practice runs where you’re judged as though you’re at an official competition, but it’s unofficial in the sense that you can’t earn points towards an agility title. True title-earning competitions are run by agility organizations, five of which are listed in Table 16-1. Each organization has its own standards for competition as well as levels, classes, and titles, which can best be understood by studying their “Rules and Regulations” guidelines or visiting their Web site. In this section, I outline differences between matches and trials, give you an overview of several national agility organizations, provide definitions for class competitions and titles, and tell you how to sign up to compete.

Choosing between matches and competitive trials

It’s helpful to understand the difference between matches and competitive trials. Matches are organized and run by regional agility clubs that set up pseudo-competitions to prepare teams to work toward earning titles. While the structure is similar to that of a competitive trial, these weekend get-togethers are held to give dogs the opportunity to practice sequenced runs and to help newbies prepare for the rigors of competition in a fun, friendly environment.

Tip

Matches are a great place to work out any kinks in your routine. These events are publicized, but far less official — there’s often no premium list (see the section “Signing up” for more details) or advance registration. They may draw big crowds, but a good run — although earning applause and congratulations — doesn’t earn you points toward any titles. Matches are an excellent way to practice your routines: Once you feel confident on the course, you’ll be ready to move into more competitive venues.

On the other hand, competitive trials are very formal. You must register early, and you’ll receive a premium list. It’s important to sign up early because only a certain number of trials are run on any given day. Seasoned agility dogs can earn a great many titles from many different organizations. In the next section, I list five different sanctioned agility clubs. There are other organizations, too: Look for ones that have a strong hold in your part of the country. Once you go to a trial, your name will be put on a list and you’ll get routine mailings of competitive events held in your area.

Agility titling lingoThe rule of thumb in listing titles is that championship titles, as well as all UKC titles, are placed in front of a dog’s name, while all other titles are placed behind it. Lolly’s Bit-by-Bit NF, a Golden Retriever who gained her Novice Fast title, is the daughter of U-ACH ADCH Lolly’s Special Girl OA, OAJ, OAC, AXJ, who has many titles to her credit. (Note: U-ACH = UKC Agility Champion; ADCH = USDAA Agility Dog Champion; OA = AKC Open Agility; OAJ = AKC Open Agility Jumpers with Weaves; OAC = NADAC Open Agility Certificate; AJX = Excellent Jumpers with Weaves.) |

Finding events through agility organizations

Agility matches and competitive trials are put on by various agility clubs and organizations. By the time you’re ready to enter a match or trial, you’ll likely be involved with an agility group that can point your way to an event. But if you’re going solo, you can find information about agility events in your area by contacting national agility clubs, as listed in Table 16-1.

Tip

If you can, find an organization that reflects your ideals and enter the competitions it sponsors. All agility organizations are not equal. Each one stresses different parts of the game. Some organizations emphasize speed, while others stress safety. One organization has longer completion times, thus enabling slower dogs to succeed, while another takes breed limitations to heart — varying jump heights to accommodate your dog’s size and body type. See Table 16-1 for a list of the top five agility organizations in the United States and what they focus on.

Table 16-1 National Agility Organizations and What They Emphasize

|

Organization

| Emphasis |

| This club promotes agility worldwide, sponsoring a yearly event in America that attracts competitors from around the world. The USDAA also sponsors a team to compete internationally. The courses are competitive, and events are divided into two categories: Championship Level, which consists of top- level courses that challenge a dog’s vitality and the team’s choreography; and Performance Level, which is more recreational. |

| The AKC offers a challenging course while allowing course times that accommodate a variety of breeds and sizes. The AKC also offers a Preferred class that lowers jump heights and lengthens the course completion time to benefit veteran (senior) or special needs teams. |

| The UKC allows more time than the other organizations for each team to complete the course. The jump heights are lower as well. |

| This group stresses speed, with course times that challenge even the best teams. Specialty classes allow for dogs and human handlers of all ages and abilities. |

| CPE is the newest organized club on the scene. It emphasizes the fun and recreational side of agility. The courses are challenging without being too rigorous. CPE offers a host of games that spotlight passions for various obstacles. |

Checking out the classes of competition

In the United States, many organizations hold weekend matches and gatherings to judge and time the performances of individual teams, consisting of one dog and her handler. Each organization has standard classes and nonstandard classes. Standard classes include obstacles with varying degrees of difficulty. Non-standard classes are games that emphasize different aspects of the sport.

Standard classes

A team who has mastered each of the obstacles in agility and can sequence them in varying order may choose to register and compete with a recognized organization. Each organization awards titles to dogs who successfully run a set number of courses. Additionally, these groups divide registrants into three competition levels: beginner or novice, advanced, and expert or masters. (Note: The names of the levels may vary, depending on the sponsoring organization.)

A beginner or novice level course consists of 13 to 15 obstacles, widely spaced for ease of communication and completion. Once a dog masters the beginner’s course and has three qualifying runs, she gets a title that represents this accomplishment. Good dog!

The next challenge is the advanced course, and then comes the master course. These courses contain 18 to 20 obstacles, arranged closer together. Faster, more difficult maneuvers are required, testing a team’s ability to discern and direct. Fewer dogs can master the advanced course, and only when a title has been achieved at that level can they test their skills at the master (or expert) level competition.

Non-standard classes

When competing for titles, standard classes are the bread and butter of the weekend trials; non-standard classes are the fancy jam spread on top. Talk to anyone involved in agility and they’ll tell you that the non-standard classes — better known as the games — are where the fun is. Each one has its own unique spin:

– Jumpers class: The course in this game is a fast-paced one, consisting of jumps, jumps, and a few more jumps. A tunnel or two may be tossed in for fun, but nothing that slows the pace of the run.

– Jumpers with weave class: This course is identical to that of the Jumpers class, with weave poles tossed in to spice things up.

– Gambler’s class: This game assigns points to each obstacle. Pause or contact obstacles have the highest point value because they take the longest time to complete. In Gambler’s class, the handler is allowed to choose the first part of the run, and the goal is to gather as many points as possible. At the end of the first period a buzzer sounds, and the team must finish a set of pre-assigned obstacles known as the gamble. This last half of the course must be directed from a distance. Gambler’s class is for advanced teams only.

– Snooker class: This game is color-coded. A course is set up, and obstacles are tagged with two or more colors. The course may be divided into blue and red obstacles, or the color scheme may be more complicated, with multiple colors used to challenge the participants. Whatever the rules of the day, in a Snooker class, a team must perform a color-sequenced run to play. For example, the rule may be red:color:red:color:red:color, until all the obstacles are complete: Here you would direct your dog over a red-flagged obstacle, then a color, then a red, and then a color until all the obstacles are complete. Sound confusing? It’s meant to be. Like the Gambler’s class, this one is for teams who have a well-tuned understanding of the sport.

– Relay class: In Relay class, multiple teams work together. Teammates may run half the course or each team may run a full course before handing the “baton” off to their teammates. Times are added collectively.

There are two types of team events:

- Relay pairs: Two teams work together.

- Relay teams: Three or more teams work together.

Signing up

Fun matches rarely have a premium list, and many are okay with drop-ins. These gatherings stress learning, practicing, and troubleshooting.

But when you choose to enter an organized trial event, you first have to write in to get a premium list, which includes all the information on the specific event, including

- The entry form

- Where and when the event is

- How many teams can register (Hint: register early)

- Height divisions

- Class specifics

- Awards

- The names of the judges

- Registration fees

Your first registration form may seem like it was written in a different language. Sure, the name and address section is pretty straightforward, but then you get to the class specification section, and that can be utterly confusing!

Each group has its own competition levels and rules for registering for the various classes. If you’re new, you’ll register for novice or starter divisions. The actual names of the various levels differ depending on the organization: Some simplify the divisions with easily recognizable words, such as beginner, advanced, and masters; others have more obscure definitions. Don’t be put off — once you learn the terminology, it will be old hat. Take a few minutes to study the standards for each competitive level.

There will be a registration fee for each trial you enter. The fees run from $12 to $50 per run (this is not set in stone), and generally no discounts are given for multiple classes or more than one dog.

Preparing for a Trial

Once you’ve signed up for a trial, stay steady in your practice runs. Don’t suddenly ramp up the intensity of your workout or increase the duration or frequency of your agility practice. If you change what you’re doing, your dog will react either by shutting down (that is, by ignoring you or running off) or worse, injure herself. If you’re concerned about a certain obstacle, troubleshoot it far in advance of a trial — not the day before. Nothing temporarily confuses a dog more than a sudden switch in handling, and while it may be necessary to modify your approach, avoid doing it right before a trial. In the following sections I give you some hints on how to get yourself ready for competitions and arrive with a smile on your face and a wagging tail beside you!

Packing for the trip

If you’ve never been to a trial, prepare yourself. You need to pack for both yourself and your four-legged teammate.

Though the premium list will usually tell you where the event is, consider the location — is it indoors or out? Will the events be run in a large open field, offering little shade or protection from the elements, or in an un-air-conditioned or poorly heated auditorium? Bring along whatever you can to keep yourself and your dog comfortable, such as water, a mist sprayer to cool off your dog’s foot pads, and/or a comfortable mat for her to lie on.

Tip

If traveling is in the plan, pack an extra set of car keys just in case you need to leave your dog in the car for any reason. That way, you can leave your automobile running with the air conditioning or heat on to ensure your dog’s comfort and stability.

If staying overnight is unavoidable, find lodging that welcomes your dog and respect the rules of the establishment. Bring vaccination records, poop bags, bowls, and a crate or familiar bed to ensure your dog is relaxed and in good spirits for your big day.

When packing your overnight bag, remember you’re packing for two. Your bag should include comfortable clothing and shoes. Dress for the day: Nothing is worse than being uncomfortable when you’re in the spotlight. You’ll likely be waiting your turn, so bring a comfortable folding chair, some favorite snacks, plenty of water, and some extra cash. Bring sunblock if it’s sunny or rain gear if the weather’s iffy. Tuck a copy of the registration form and premium list into a folder for quick reference.

Your dog’s bag should include her food, bowls for water, familiar bedding, and a crate (if she’s accustomed to one) or a gated pen in case you must leave your dog alone. Bring anything that will help your dog feel at home in this unfamiliar place: favorite toys, a cozy blanket, treats, and so on. Most importantly, keep yourself calm — nothing reassures your dog more than your happy mood.

Tip

Before you set out to your first event, check with your veterinarian to ensure your dog’s vaccinations (including bordetella or kennel cough) and heart-worm testing are up-to-date. Competitions bring together all sorts of dogs: Make sure yours has a clean bill of health coming and going!

Arriving on the scene

The first thing to do when you get to a trial is to take a deep breath. Look around you. Find the registration table, and see where people are setting up their dogs. Be mindful of your four-footed partner — remember, she can’t “see” where you are — she needs to sniff about to feel most at ease. Give her a five-minute walk around to sniff her surroundings, and let her relieve herself and settle in before you check in and set up.

Before you unpack, walk to the registration table and check in. Be polite to the stewards, many of whom have volunteered their time — your gratitude will be greatly appreciated. If you didn’t receive your confirmation ahead of time, you’ll get one at this time. Review it, determine when the judges’ briefing and walk-throughs are held (see the upcoming section “Getting to know the course”), and note the running order and locations of the various classes. If you don’t get a course diagram, ask where you can view it. Respect the organization’s rules and regulations, and arrive on time to allow your dog to get set up before the trials begin.

Tip

At the registration table, you’ll receive an arm band or sticker that will highlight your dog’s class specifics. Wear it on your shirt or shirtsleeve.

Setting up

When you first arrive at an event, you’ll need to find an area to arrange yourself and await your run. Find a setup location that’s within the allotted “dog” area. Be respectful to those around you; don’t crowd others or take up too much space. Here are some other rules:

– Always clean up after your dog.

– Never touch or allow your dog to interrupt another dog without the handler’s permission.

– Be mindful of what you say. Stick to the “positive” rule — if you don’t have something nice to say, keep quiet.

– When your class is running, watch respectfully. Get to the ring early and check in with the steward. Not only will you be ready for your turn, but your dog will also have a chance to settle into the routine.

– Remove training collars before you get onto the grounds. Many organizations require that dogs run naked (without a collar) or with a flat-buckle collar.

– Speak and act respectfully to the judge. Say hello and follow his or her directions. If your dog acts up or you need to leave the ring early, always ask the judge to be excused.

Helping your dog relaxThere are dogs, like people, who are comfortable in any surrounding any time. Mind you, this is the exception, not the rule. Young dogs in particular need more time to relax in new surroundings — older dogs are seasoned by years of experience. Remember, nervousness is contagious! So, breathe deeply. Yes, you. Keep your tone relaxed and comfortable, and stay focused on your surroundings. Act like you’ve been in this situation before and you know just what will happen and what to do. Your dog will take her first cues from you. Keep your dog on a leash and limit your commands. Over-commanding your dog pre-trial will put her on edge. The best thing to do is to lead her to a quiet, shady spot if you’re outdoors and sit down. Pet your dog calmly when she relaxes next to you. Give your dog a displacement bone — a favorite chew that she hasn’t seen in a while. Like kids, your dog will appreciate having something to do. Don’t stare at or talk to your dog unnaturally. Your focus will trigger her worry. In your dog’s mind, your attention communicates that you’re unsure of yourself and anxious. |

Warming up

Before you perform, give your dog an adequate warm-up. A few laps around the facility or a 5-minute toss will get her muscles moving and ready her for her pending workout. If you’re animated on the course, stretch yourself out as well. Gear up for the day by waking both your bodies up gradually. This interaction will also help to offset your jitters and help your dog to relax.

Getting to know the course

Every organization invites you to know the course at some level before you compete. You’ll either be invited to walk it solo or with your dog, which is best to do on-leash. One organization, the UKC, allows you to walk your dog through the entire course to familiarize her with their equipment designs and setup. Rules and standards for every organization change, so request and read through the club’s rules when you register, and be on time for these pre-performance programs.

Judges’ briefing

Before running the course, you and other competitors from your group will have a change to meet with the judge/judges at the judges’ briefing. How many judges there are is determined by the type of event and the level of competition. You’ll hear the rules, course time, and any specific expectations. If you have any questions, this is the time to ask them.

The walk-through

On the day of competition, the judge will arrange the obstacles in a unique pattern. You’ll have ten minutes to walk through the course with other competitors to determine your strategy. The course obstacles will be numbered with orange cones to help you organize your footpath more easily.

As you’re walking the course, imagine your dog is with you. Try to determine her speed and dependency on your position. Can you send her ahead to jump while you line yourself up at the next obstacle? Where might you need to cross over or cross behind? Have you perfected the get out so that you’re able to send your dog out to cross the finish line ahead of you?

Agility trials begin when your dog crosses the starting line. If her “Stay” command is rock solid, you can leave her at the start and position yourself near the first set of obstacles; otherwise, you’ll need to run with her.

Remember

While you can get some clues watching how more experienced handlers orchestrate their performance during the walk-through, their dogs may be capable of different maneuvers than your dog is ready for. Stick to what you know on competition day — don’t try anything new!

Familiarization: Bringing your dog in the ring

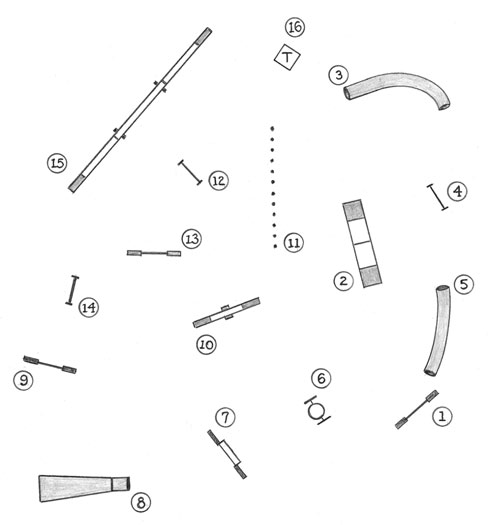

Some organizations allow you to walk the course with your dog, memorizing the run before the competition begins. You must make careful note of the exact pattern of the obstacles; points are lost if you miss an obstacle or do them out of order. The layout in Figure 16-1 represents a sample novice course with 16 obstacles. A team approaches the starting line. At this point, the handler can stand with his or her dog or leave her in a “Stay” to get a better directing position on the field.

Contact familiarization (AKC)

The AKC allows handlers to take their dogs into the ring ahead of time to familiarize them with the contact obstacles. It’s a good idea to do this on-leash because it can be a chaotic mix out there. During this period you’re permitted one walk-through per obstacle. If your dog bails or balks, that’s it. You had your turn: Don’t test the system or you may be disqualified.

Tip

This is a good time to work on your dismounts, reminding your dog to hit her contacts no matter when, no matter where.

Course familiarization (UKC)

Here you’re able to walk your dog through the course on-leash ahead of time. Determine your footpath and urge her through with the same words you’ll use during your trial.

Figure 16-1: A sample course layout.

The UKC organization uses several obstacles that differ slightly from other, more mainstream agility equipment. On UKC courses, you may see a crawl tunnel, a swing plank, and a sway bridge. See the sidebar in Chapter

Considering Agility Training for more information about these obstacles.

Ready, Set, Go! Running the Course

As your running approaches, calm yourself with positive visualization. Remember that dogs can sense your emotions: When you’re nervous, you omit a faint but dog-detectable “worry odor.” Not only will your dog sense it, it will unnerve her too. (If you find nerves to be a real problem, check out Conquering Ring Nerves: A Step-by-Step Program for All Dog Sports, by Diane Peters Mayer [Howell].)

Get to the starting area as the previous dog is midway through her run. When your time is called, remove your dog’s leash and/or collar and hand it to the entrance steward.

Give a final good-luck pat to your dog, and get ready to run. Remember, you’re not allowed to touch your dog or give her other incentives, such as food or toys, once the clock has started.

On your mark, get set, GO! No matter what happens between the starting and finish lines, you’ll both be okay. Life is good. You have each other. Do your best. You’ll either have a good run or something will run amuck.

No matter what happens, use every experience as a learning tool. Following are some frequent mishaps. Should they happen to you, you’ll be in good company.

– Course confusion: Believe it or not, you may get your obstacles mixed up in the middle of a run. When your heart is racing, it happens. Look for the numbered cones, or pause, gather your senses, and reorient yourself.

– The “oops” touch: In your head, you know that you can’t touch your dog during the run. Those are the rules, no exceptions. But then, oops . . . you can’t help yourself. Though you’ll likely be disqualified, it happens to the best of teams. Continue your run, politely stopping if the judge signals you. (Politely apologize to the judge — and your dog — before leaving the ring.) It’s a truly embarrassing moment — try to avoid it.

You’ll need to handle your dog if she falls off an obstacle and hurts herself. Turn to the judge, acknowledge your decision to leave the ring, and go calmly. Some courses have an onsite veterinarian; in other cases, the workers will direct you to the nearest animal hospital.

– Failed attempts: Your dog may refuse an obstacle. Maybe once, maybe twice — maybe until the judge urges you to go on or leave the ring. Perhaps it’s the way the sun is shining on the obstacle or the funny smell of coffee that someone dropped while setting up the obstacle earlier in the day. You may never know — you’re not a dog. Regardless, repetitive refusal results in a non-qualifying run (also known as an NQ). Let it go, and either go on and finish the course or look to the judge for his or her preference.

– On-course pottying: This is a not-too-uncommon faux pas which can often be avoided if you walk your dog five minutes before her turn. Some dogs eliminate in order to release stress. If you’re a newbie or you’ve been traveling or tense yourself, this may be a signal of the novelty. Don’t feel too bad — even experienced dogs are known to do this from time to time. You will be excused from the ring immediately, however.

– Table run-off: They’re the longest five seconds on the agility field — the ones the judge counts out loud while your dog holds still on the pause table. If she jets off, return her quickly and the judge will count again. Remember to wait until the judge says “GO!” to release her.

– Off-course runs or missed contacts: While you’re running your dog, she may miss a contact, run off-course, or skip an obstacle altogether. Don’t stop! While most judges catch every misstep, some don’t, and even though your penalties may net you an NQ, give your dog the pseudo-thrill of finishing the course. Your dog won’t know the difference. Your positive elation will have a far greater and lasting impression than your getting all bummed out about a few lost points on the score card.

Tip

Ask other more-experienced teams how they deal with NQs and how you can help your dog improve. (Also turn to Chapter Sequencing and Troubleshooting Your Agility Moves for some advice on troubleshooting.)

Relaxing Once Your Run Is Over

Once your run is over, cool down your dog by giving her a few sips of water, spaced a few minutes apart, until she seems content, and then take her on a walk. Like people, dogs’ bodies are geared for competition and need a cool-down period to shift back into relaxed mode.

Of course, you’re done, so you can pack up your car and go home — especially if you feel you’re out of the running — but when possible, stick around. Cheer on other competitors, and learn from their successes or mistakes. Study the judge — you’ll likely see him or her again, and it’s helpful to learn how each analyzes a run. Most of all, take the time to make some human friends. You’ll share a common bond right off the bat! Having friends to offer support, practice with, and learn from makes this sport safer for your dog and a lot more fun!

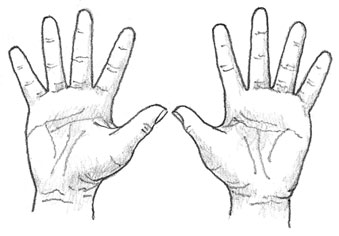

Judges’ signals

During a run, the judge will use raised arm signals to score the performance. Here are a few common signals and what they mean: – Closed hand: This signals a refusal.

– Open hand: In the AKC and UKC, this signals an off-course; in the USDAA, it symbolizes any standard fault.

– Two hands raised: This registers a disqualification in AKC and UKC; for the USDAA, it automatically deducts 20 points from the total score.

– A “T” symbol (or two fingers raised): This represents a table fault in the AKC.

If you hear a whistle blow, stop and face the judge. A whistle can mean different things. The judge may disqualify you, he may order a fresh start, or he may have another reason for breaking your run. |

by Sarah Hodgson