In This Chapter

- Finding out what’s involved in agility

- Taking a look at course obstacles

- Assessing whether your dog has what it takes

Discovering Agility

Remember

Agility is an amazing way to spend time with a dog. No matter the level at which you choose to participate, you will be teaching, and your dog will be learning and looking to you for direction. Together, you’ll build skills and master obstacles, collecting those magical “Ah-ha!” moments when you and your dog just flow.

It’s All About the Obstacles

Jumps

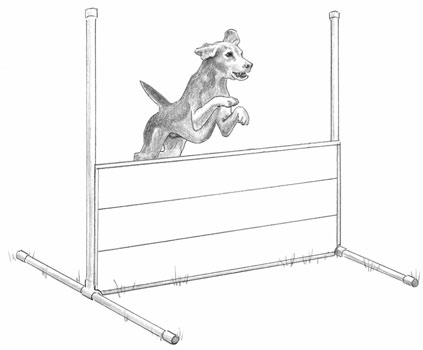

– Bar jumps: A bar is spread between two poles and set at a specific height. The height is determined by the dog’s size, as measured at his shoulder (also known as the withers). See Figure 11-1.

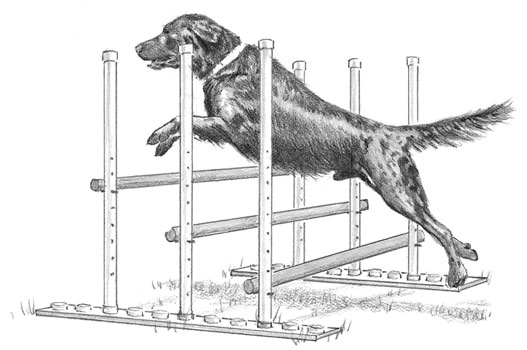

– Spread jump: Multiple bars are arranged to test a dog’s ability to jump high and wide. See Figure 11-2.

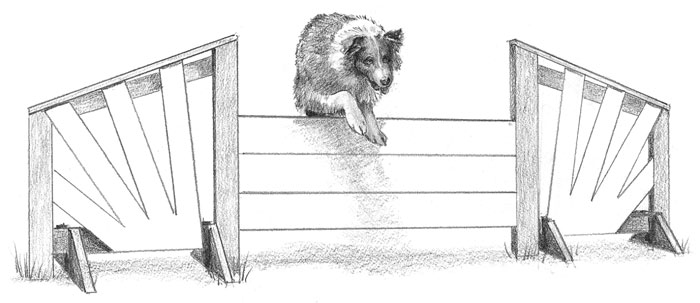

– Jump with wings: This jump has decorative sides to instill a handler’s ability to direct from a distance — the sides block the handler from getting up close to the jump itself. See Figure 11-3.

– Panel jump: This one looks like a solid wall. A dog must clear this jump without touching it. Hard to do — from my vantage, climbing over looks like more fun! See Figure 11-4.

– Tire jump: A tire or tire-like object is anchored in a frame. Jumping through it seems hard enough — but a lot of precision is also required to take this at full speed. See Figure 11-5.

– Broad jump: This is the only jump brought over from the obedience ring. Panels are laid out to a premeasured width to test a dog’s ability to jump low and long over the width. See Figure 11-6.

Contact obstacles

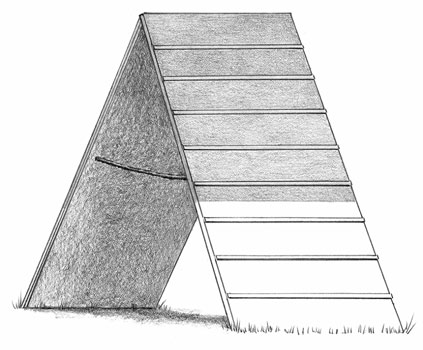

– The A-frame: Two 4-foot panels are arranged at a climbing angle (specified according to the size of each dog in timed trials). A dog must climb up — that’s the fun part — and then descend carefully. See Figure 11-7.

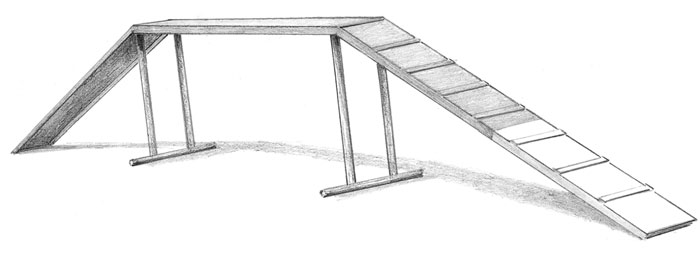

– The dog walk: This obstacle looks like a cross between a balance beam and a bridge. Suspended 3 to 4 feet above the ground, balance is everything — jumping off early is a big no-no. Geared for the finish, a dog who has learned to run through the obstacle safely running through the colored zones, is a master of self-control. See Figure 11-8.

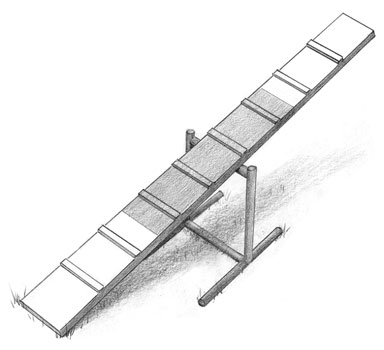

– The teeter: This one looks like a seesaw from a school playground. The teeter’s 1-foot width tests a dog’s balance and self-control. He must run up the teeter in a controlled fashion, pause as the obstacle shifts downward, and then run off — running through the colored zones as he goes! See Figure 11-9.

Tunnels

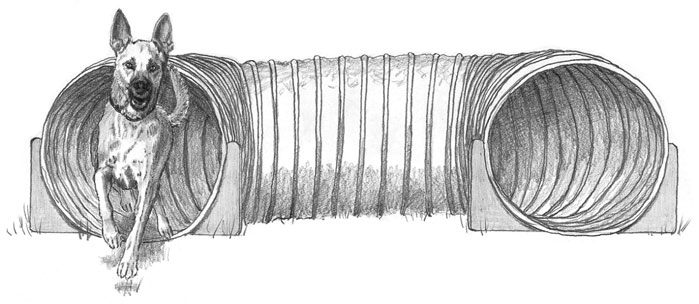

– Open tunnels: This type of tunnel is open at either end and can be arranged as a straight-line run-through or angled to test a dog’s processing skills as he’s running at top speed. See Figure 11-10.

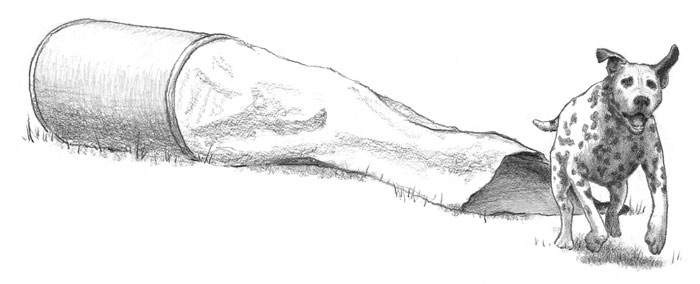

– Closed tunnels: These tunnels sport a wide, barreled opening with an attached draping fabric section, or chute, that a dog must tunnel through to emerge. See Figure 11-11.

Perhaps the most comical term in agility is tunnel sucker. This dog has a fetish for tunnels and will routinely break from other activities for a quick run through a tunnel!

Agility UKC-styleThe United Kennel Club (UKC) has some unique obstacles that aren’t seen in events sponsored by other agility clubs. The UKC’s crawl tunnel simulates the movements of a typical tunnel, but it looks more like a ribcage than a closed chute. The swing plank and sway bridge simulate the moves of the dog walk, but these obstacles differ slightly in that they swing. Whether you compete in UKC events or not, you gain diversity practicing on these obstacles if you can find them! For more information on these UKC obstacles, visit their Web site at www.ukcdogs.com. |

Weave poles

This obstacle sports 6 to 12 upright poles that a dog must weave through. It sounds easy, and maybe even a little fun. But people who love agility will tell you that this is one of the biggest challenges on the course!

Calling all dogsOne thing I love about agility is that there’s a venue for everyone — even at the competitive level. Purebreds and mixed breeds mingle, testing both the course and the clock. Jumps and contact obstacles are adjusted for dogs of different heights and ages. True, you may not win the highest score with your 12-year-old mini Dachshund, but you two can get out there and run — or waddle if necessary — with the best of them. There are classes for junior, senior, or disabled handlers as well. Admit it — it sounds like fun, doesn’t it? If you’ve got the gumption — and a fit and agile dog — read on. See if the agility bug bites you! |

Table

Deciding Whether Your Dog Has What It Takes

Agility as a confidence boosterIn my work as a trainer, I often run into dogs who “act like wild animals” according to their frustrated caregivers. They jump and nip and pull uncontrollably on the leash. Very often, it turns out that these dogs are acting up because they’ve never been taught how to behave. Mishandled and misunderstood, many of these “unmanageable” dogs come around quickly with some basic training skills and become wonderful, eager-to-please companions. I often recommend a sport like agility to refocus their energy and reward their drive to please — and play. Consider your dog: If he hasn’t been trained and behaves wildly, it may simply mean that he doesn’t know what you expect. Work on the foundations of good behavior, and your dog just might surprise you. You could have a diamond in the rough — an agility master in the making. I took my first agility class with a mixed-breed Terrier rescue named Hope. Feisty and disgruntled, Hope had been tossed a few lemons in life. Jumps weren’t Hope’s thing, and she wouldn’t set foot on the bridge. But the A-frame! Hope came to life on the A-frame. On the way up, she would concentrate, her head bent low and her expression deadly serious. Coming down the other side, she’d open up, head and tail held high for all to see. Hope, Queen of the A-Frame! Those two sections of scratched-up wood gave her so much joy; I would look forward to our class work all week long. While we never entered an event, we still had a great time together, and it did wonders for her attitude and confidence. |

Personality traits suited to agility

– Gumption: Agility dogs have gumption. They see a new object and want to investigate it. They get energized when they see other people and dogs. They like new adventures. Sound familiar? Does your dog do back flips when you jingle your keys? That’s gumption: an adventurous spirit.

– Focus: This sport requires attention to details and an ability to filter out distractions and stay completely focused on the task at hand. In order to excel in agility, a dog needs to be addicted to action, attentive to verbal direction, and mindful of subtle body cues.

– Determination: Agility is a “can-do” sport — one that requires a fall-down-and-get-back-up attitude. Why walk if you can run? Why hurdle a jump when you can sail over it? A dog who is willing to try something new and repeat it again and again until it feels natural will enjoy the rigors of agility.

– Cooperation: Agility is a team sport. Dogs who are motivated to follow direction and trust their people do best at it. Often competing in close quarters with other dog-person teams, a dog must pledge full allegiance to his partner and be able to ignore anything else that might be going on.

– Sociability: This sport involves a lot of socializing — with dogs and people, sounds and stimulations, unfamiliar objects, and unpredictable activity. If you go to weekend events, they can last all day. Will your dog be up for it? Will you?

Remember

As you’re reading over these attributes, remember agility is a team sport. Not only will your dog need these attributes — you will too! Agility requires bending, turning, and running while staying upbeat and focused. The bottom line? While you won’t need to scale any walls or leap tall buildings, you will have to exert yourself out there.

Tip

Don’t overlook agility because you don’t think a competitive sport is right for you. When you participate in agility, you’re not really competing against someone else — you’re competing against yourself. It’s just you and your dog against the clock and your own expectations.

Evaluating your dog’s body type

Take a minute and imagine your dog’s skeleton up on the wall like one of those posters you see when you go to your veterinarian. All dogs are not created equally. Consider how your dog’s form will affect his ability to function.

Tip

If you observe or take a class, speak to the instructor to ensure he or she will be mindful of your dog’s particular needs during practice rounds and mock competitions. A novice Basset Hound can’t perform at the same level as an experienced Australian Shepherd. Modify your expectations for the size and breed of your dog. Following are some characteristics that may affect your dog’s ability to participate in agility:

– Angular posture: The perfect agility specimen looks a lot like a Border Collie. Angled hips set to propel forward at top speed, sloped shoulders, which serve as the perfect shock absorbers as the dog leaps, twists, and balances on the obstacles. It’s no surprise that this breed excels at the sport of agility, as do Australian Shepherds and Whippets.

– A deep-chest: As a general rule, deep-chested dogs have a tendency to trot rather than run. They jump by lifting their heavily boned frames up into the air and coming down with a harrumph. Modify jump heights and dissention angles to ease their efforts and the shock to their physique. Keep your enthusiasm high to encourage their speed and participation. Deep-chested breeds include the Giant Mastiff, as well as Sighthounds and Mountain Dogs.

– A straight back: Dogs with straight backs are flat-lined and not well angled to absorb the shock of repetitive leaps, sharp-angled landings or turns, and jarring stops. When practicing, keep the jumps low and spread the angle of the contact obstacles so the dismount isn’t jarring or abrupt. Straight-backed dogs include Corgis, Terriers, Retrievers, and Shetland Sheepdogs.

– A long spine: While Pretzel-the-Dachshund might get super-charged at the thought of competing, he certainly shouldn’t be forced to do repetitive jumps or scale obstacles set at sharp angles. Long dogs have tricky spines and temperamental discs: Be mindful of this — your dog’s spine is the only one he’s got. Along with Dachshunds, Corgi breeds and Basset Hounds fall into this category.

– A short snout: Dogs with short snouts have a rougher time oxygenating than other dogs. Don’t push them when they’re working to catch their breath. These breeds are often barrel-chested and top-heavy as well. Ramps should be set at gradual angles, and jumps should be positioned inches below the elbow. Bulldogs and Pugs fit this characterization.

Tip

It’s a good idea to check with your veterinarian for recommendations regarding any limitations that may apply specifically to your dog before beginning agility.

Being realistic about sensory limitation

Considering your dog’s age

Giving a puppy a head start

– Socialize your puppy with people and dogs, but control the experience. Dog parks are fun but can be over-stimulating. Be mindful of who is influencing your puppy and how — don’t let him interact with aggressive dogs or rough players of any species.

– Expose your dog to a variety of sights, sounds, and experiences. Walk him through town, in the woods, and near natural bodies of water. Make sure he’s comfortable walking on carpet, wood flooring, and AstroTurf.

– Bring your puppy to an agility event or class just to watch the older dogs perform. (Call the organization first to ensure they’ll allow noncompeting dogs to attend.) Let your dog experience the bang of the teeter-totter, the calls of competitors, the barking, the cheering, and the general happy mayhem associated with agility gatherings.

– Encourage your dog’s curiosity with exploratory games. Lay a ladder flat in your yard and lead him over it. Lay a broomstick on the floor and pretend it’s a jump. Rest a 12-inch plank on the ground and lure your puppy straight across!

– Get started teaching basic obedience directions like the ones listed in Chapter Encouraging Self-Control before You Launch into Lessons. Familiarize your maturing puppy with directional cues, such as “Go out” and “Left” or “Right,” by repeating these words as you toss a toy or move in each direction.

Advancing during adolescence

Considering older or veteran dogs

– Our dogs’ bodies age just like ours do. Cartilage weakens, bones become more brittle, and muscle tone and flexibility decrease. Exercise keeps the body fit, but too much vigorous exercise can lead to joint and muscle injuries.

– Conditioning is an important part of the training routine for any dog, but for older dogs, it’s essential. Keep your senior athlete slim, and make sure all exercise sessions are bracketed by a gradual warm-up and cool-down.

– How are your dog’s eyes? Cloudy, compromised vision will make it difficult for your dog to gauge his position on the course, and this could present a safety issue. If your dog’s vision is poor, it’s best to find another activity.

If you’re thinking of beginning agility with an older dog, get your veterinarian’s approval first. Find an agility instructor who understands your dog’s limitations, and adjust jump heights accordingly.

by Sarah Hodgson