In This Chapter

- Grouping dogs into breeds

- Understanding breed groups

- Sorting out mixed breeds

- Predicting dog behaviors from breeds

In this chapter, we take the word breed and look at its value in helping you understand your dog. If you’ve ever watched a dog show, you’ve probably noticed a lot of different types of dogs prancing around the ring all prim and proper, some with little bows, others with their fur sculpted like ornamental hedges. In case you have the idea that a breed is nothing more than a fashion statement, we’ll take the time to educate you on the psychological, emotional, and physical needs and differences between each and every dog breed you see.

What Are Dog Breeds?

The essence of creating specific breeds of dogs was to guarantee that useful characteristics were passed on from one generation to the next. Careful breeding records were kept for each puppy, tracing its genetic lineage and establishing a group of dogs that were purebred.

The job of kennel clubs is to file and organize all the breeding records of each dog, and to record every mating to ensure that there has been no outbreeding, which is simply defined as mixed matings between dogs of different recognized breeds. Kennel clubs also establish the standard of the breed, which is simply a description of what the ideal dog of a particular breed should look like, what its distinctive natural behaviors are, and what its personality or temperament should be like.

Checking out the top dog shows Westminster Kennel Club and Crufts are two world-renowned dog shows that highlight the top dogs in each breed recognized in their kennel club roster. Crufts, the largest dog exhibition event in the world (attracting more than 20,000 entries each year), began in England in 1886. The Westminster Dog Show (whose winners are considered to be the top dogs in North America) is held at Madison Square Gardens in New York and began its competitions in 1877. Check them out on television or in person if you’re able. |

The American Kennel Club (AKC) recognizes around 160 breeds of dogs categorized into seven groups: sporting dogs, hounds, working dogs, terriers, toy dogs, nonsporting dogs, and herding dogs. The AKC is sort of the Microsoft of dog clubs and serves as the standard around the world, so we refer to its listing throughout the book.

The AKC also has a Miscellaneous Class for breeds recognized in other countries or by other kennel clubs, but that aren’t yet recognized by the kennel club. Nearly every year, one or more breeds are recognized and moved from the Miscellaneous Class to one of the other groups, and additional new breeds are added to the Miscellaneous Class.

Several breeds of dogs were created based on their aesthetic appearance alone. The Cairn Terrier and West Highland White Terriers, for example, started out as the same breed. In each litter, some dogs were white, and some weren’t. Because the whites produced other white-colored dogs when interbred, they were separated into two distinct breeds. Structurally and behaviorally, the two breeds remain virtually identical. The Norfolk and the Norwich Terriers are another example of breeds that only differ in the shape of their ears (Norwich has pricked ears and Norfolk floppy ears).

RememberThis division of dogs based solely on appearance is a distortion of what breeds are all about. Dogs were originally domesticated because they had skills and behavioral traits that made them useful. What makes this important for understanding the psychology of dogs is that creating a breed was originally an attempt to create lines of dogs that had predictable behaviors and temperaments.

A New Breed of Dog Classification

In the interests of presenting breeds according to their behavior and psychology, we divide the AKC’s seven groupings into subgroups. Each group is based on a dog’s breed’s individual behavioral characteristics.

For example, we divide the dogs in the herding group into drovers (who work more independently and move flocks over great distances) and herd minders (who move flocks about the farm, generally under the guidance of a shepherd). Behaviorally speaking, drovers are more independent and likely to roam, where as herders are intensely focused and stay centered about their flock.

Sporting dogs

Sporting dogs are bred to help man hunt. Though blasting a defenseless duck from the sky likely isn’t necessary for survival, don’t tell your dog. He still views his purpose with high regard. Fortunately, you don’t have to take up hunting to keep one of these dogs happy: a tennis ball or Frisbee works just fine. However, knowing specifically what your dog was bred to hunt can help you better understand your dog’s behavior.

Just for funThe Labrador and Golden Retrievers are among the most commonly used service dogs, assisting blind or handicapped people, and also detecting drugs or explosives and assisting in search-andrescue tasks.

Technical stuffGo to England, and you’ll find the hunting dogs under the title Gun Dogs. In America, they’re referred to as sporting dogs.

The sporting group actually contains five different types of dog, each of which has somewhat different purposes and thus may be expected to have different behavior patterns:

- Retrievers: Dogs in this group are bred to retrieve fallen game, which turns out, in family life, to be a dog who is alert, has a good memory, and is eager to participate and please. Because their intended purpose demanded close human contact and direction, retrievers are sociable and attentive. Chesapeake Bay Retriever, Curly Coat Retriever, Flat Coat Retriever, Golden Retriever, Labrador Retriever, Miniature Poodle, Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever, Standard Poodle.

- Pointers: These scouts of the dog world have an attentive eye and nose for game. Though they work more independently than a retriever, and certainly have been bred to expend more energy in the pursuit of quarry, the pointers are patient — originally so patient they would hold a pointing pose until the hunter got into position and (finally) released. Brittany Spaniel, English Pointer, German Shorthaired Pointer, German Wirehaired Pointer, Pointer, Wirehaired Pointing Griffon.

Technical stuffWhen a pointer finds game, it exhibits a behavior that contradicts evolution. Instead of rushing forward to capture its quarry, a pointer freezes in position with its head pointing to where it believes the quarry is hiding.

- Setters: Pointers and setters have a lot in common. Think of setters as being faster and more exuberant versions of pointers. Their name comes from an old English alternative for the word sitter. Like pointers, their job was to find the game and then indicate its position to the hunter by sitting or crouching down and looking directly at it. They then had to hold that position until the hunters had time to drop a net over the covey of birds. English Setter, Gordon Setter, Irish Setter.

- Spaniels: These are high-energy hunting dogs that have been bred to quarter the field to find and flush game. When they’re working, they dash around searching for scents. However, when they find their quarry, they don’t wait for the hunter, but simply charge at the birds to cause them to take flight so that the hunter can take his shot. When their hunting genes are no longer in high demand, exercise and interaction will be! American Water Spaniel, Clumber Spaniel, Cocker Spaniel, English Cocker Spaniel, English Springer Spaniel, Field Spaniel, Irish Water Spaniel, Sussex Spaniel, Welsh Springer Spaniel.

Just for funThe name spaniel was given to them because of their friendly, loving nature. The span in spaniel is for Spain, which at the time was considered to be the nation of lovers.

- Multipurpose hunting dogs: Some hunters set their sights on creating an all-around, multipurpose hunting dog who would do all the main functions, such as pointing, flushing, and retrieving game. These stunning adaptations, basically mixing other dogs from the preceding groups, have all the general demands of a sporting dog, yet all the benefits, too. Portuguese Water Dog, Vizsla, Weimaraner.

Just for funThese manipulations of dogs continue today, and there is now a line of Pointing Labrador Retrievers, which, as the name indicates, not only retrieve but point as well and they may someday be a separate breed.

Hounds

“You ain’t nothing but a hound dog” doesn’t actually reflect favorably on these loving, though independent, dogs. Hounds are also hunting dogs, but were designed to work without human guidance or intervention. The human hunter is only needed if the game finds refuge in a den, burrow, or tree or is too large and dangerous for the dogs to kill. In all other cases, these hounds are supposed to be able to dispatch their target when they catch it, without any human help. How does this play out in today’s society? These dogs are still motivated chiefly by their passions, though they’re often amiable and happy-go-lucky.

Hounds naturally fall into two clear groupings:

- Scent hounds: These dogs are supposed to track their quarry by the faint odor they leave as they move over the landscape. Their noses are highly developed for this purpose. American and English Foxhounds, Basset, Beagle, Black and Tan Coonhound, Bloodhound, Harrier, Otterhound.

- Sight hounds: These dogs have keen eyesight and tremendous speed. Their task is to visually locate their quarry in the distance and run it down. Afghan Hound, Basenji, Borzoi, Greyhound, Irish Wolfhound, Saluki, Scottish Deerhound, Whippet.

Warning!Though we don’t depend on hounds for our sustenance, their instinct to hunt is still very much intact. Let a scent hound (such as a beagle) loose, and he’s likely to disappear, whatever the terrain, as he follows some interesting smells. Unharnessed, a sight hound won’t be able to resist the temptation of chasing after a mobile tidbit, which may be a neighbor’s cat or a kid on a skateboard. Best to keep these dogs leashed in open areas at all times.

The fastest animal in the world? When creating special-purpose dogs, humans developed some breeds that can run much faster than wolves or other wild animals. The fastest of these are the sight hounds, and the greyhound is the gold medalist. While the average dog can run about 19 miles per hour, greyhounds can run at speeds of 35 to 40 miles per hour. You may have heard that the cheetah is the fastest animal in the world, because it can dash at speeds around 65 mph. However, this speed is reached only for short runs that may last a few seconds and seldom covers more than an eighth of a mile. Greyhounds, however, can run at their top speed for distances as great as 7 miles. That means that although the cheetah can win the short sprint race, in any long race, the greyhound will leave him way behind, panting in the dust. So who really is the fastest animal in the world? |

Working dogs

Working dogs like to . . . work. They’re a task-oriented group that feels most fulfilled when they have a job. Though each dog in this group shares a practical function, the behaviors and temperaments needed for varying tasks can be quite varied and different:

- Guard dogs: These dogs were originally designed to protect livestock or territories without any human direction. Though a person may not desire such a devoted guardian in their home today, this point needs to be driven home. Both then and now, a human didn’t have to be home to trigger defensive reactions. Bullmastiff, Dalmatian, Great Dane, Great Pyrenees, Komondor, Kuvasz, Mastiff, Rottweiler.

- Personal-protection dogs: Although these dogs are also guard dogs, they differ in that they’re supposed to work intimately with people, under direct human control. Think of it this way: A guard dog is like an automated security system, while a personal-protection dog is more like a human body guard. Boxer, Doberman Pinscher, Giant Schnauzer, Rhodesian Ridgeback, Standard Schnauzer.

- Draft dogs: These dogs were bred to pull carts and carry packs. Most people have difficulty recognizing how important dogs were for transportation prior to the invention of motor vehicles. Dog-drawn carts were perfect for old cities where streets were often too narrow for a horse cart to negotiate. Furthermore a working man could keep his dog in his house with his family, with no need to have a stable and outbuildings. Bernese Mountain Dog, Newfoundland, Saint Bernard.

Jus for funThe Rottweiler actually began as draft dog, pulling butchers’ carts and then guarding it while the butcher was inside making deliveries. After awhile, however, its guarding functions became more important so we now classify its breed as a guard dog instead of a draft dog.

- Spitz-type dogs: These northern dogs are bred to withstand cold temperatures, and many were intended to pull sleds. These dogs have pricked ears, sharp muzzles, a flowing tail that curls high over their backs, and often dense insulating coats. That tail carried high may be all that distinguishes some of these dogs from arctic wolves, and their temperament often reflects this upbringing as well because they’re frequently suspicious of strangers and are very concerned about dominance and status in their social life. Akita, Alaskan Malamute, Chow Chow, Keeshond, Norwegian Elkhound, Samoyed, Schipperke, Siberian Husky

Terriers

Terriers may be big, small, and every size in-between. These tenacious, spirited dogs add punch to the word “zing.” Bred originally to keep homes and farms vermin-free, they bring their original feistiness and heart into the 21st century. As history progressed, certain breeds were streamlined, and the “fight” was accentuated in certain breeds that were ultimately changed into fighters for the amusement of humans. Though this “sport” still continues in underground circles, the current breeders of the fighting terriers have been mindful to diminish this impulse by selective breeding.

Terriers fall into two main groups:

- Vermin hunters: The majority of terriers were purchased and bred to rid homes and farmland of all sorts of pests — from a lowly mouse to foxes, badgers, and other poultry-killing vermin. Many of the breeds were deliberately kept small and agile to meet the task of digging underground, or wriggling their way into burrows or dens to find their targets. The coats of the terrier also played into their design because their rough, hard, or wiry coats can protect them against abrasion from rocks and rough ground and also provide a kind of armor against the teeth of their quarry.

The size differential also gives a clue into the exercise requirements of the individual breed, as short-legged terriers were carried in a basket on horseback during hunts, whereas larger terriers were designed to run with horses and hounds on the hunt. Airedale Terrier, Australian Terrier, Bedlington Terrier, Border Terrier, Boston Terrier, Cairn Terrier, Dachshund, Dandi Dinmont Terrier, Irish Terrier, Kerry Blue Terrier, Lakeland Terrier, Manchester Terrier, Miniature Schnauzer, Norfolk Terrier, Norwich Terrier, Parson Jack Russell Terrier, Scottish Terrier, Sealyham Terrier, Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier, Silky Terrier, Skye Terrier, Smooth Fox Terrier, Welsh Terrier, Wire Fox Terrier, West Highland White Terrier.

- Fighting dogs: Some dogs were bred specifically to participate in blood sports. They were put into arenas (called pits) and forced to fight bulls, bears, or other dogs. The natural scrappiness of the terrier was enhanced to make these dogs tough and willing to fight. American Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Bull Terrier, Staffordshire Bull Terrier.

Warning!Expecting a terrier not to bark may be the definition of asking too much. Specifically, all terriers were bred to bark, and barking is part of the definition of a terrier’s behavior. Though the necessity to alert a hunter to the location of the quarry by barking isn’t often sought after by terrier owners, it comes with the package. Though you may be able to curb the tenacity (see Addressing and Solving Problem Behavior), the urge to be heard will never go away completely.

Toy dogs

Though decidedly not toys, each of the dogs in this group were bred for one purpose and one purpose alone: to be cuddled. Though they are quintessential companions and require less exercise than larger dogs, these breeds still have the heart and mind equivalent to that found in much bigger dogs. Though the urge to baby these dogs may be overwhelming, hold off spoiling them until you have some structure in place. Otherwise, as they say, you’ll pay the price. Affenpinscher, Bichon Frise, Brussels Griffon, Bulldog, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Chihuahua, English Toy Spaniel, French Bulldog, Italian Greyhound, Japanese Chin, Lhasa Apso, Maltese, Miniature Pinscher, Papillion, Pekingese, Pomeranian, Pug, Shih Tzu, Tibetan Spaniel, Tibetan Terrier, Toy Poodle, Yorkshire Terrier.

Herding dogs

The herding dog group contains dogs that were used, at least originally, to herd, drive, and protect livestock. Though those traits aren’t often necessary, don’t tell a herding dog. Task-oriented and driven, they’ll find something to herd or protect — and watch out. If you don’t provide a proper outlet, the one they may be herding or protecting just might be you! There are actually two types of herding dogs:

- Drovers: These hardy dogs were bred to drive sheep and cattle over long distances, often with minimal or no direction from humans for long periods of time. Australian Cattle Dog, Bouvier Des Flandres, Briard, Cardigan Corgi, Pembroke Corgi.

- Herd minders: These dogs were indispensable to shepherds because of their ability to keep herds of animals together and to move them short distances. They work closely with, and under the direction of, a human shepherd. At home, this turns into a dog who will either look to you and your family as a sheep or a shepherd. In short, you better train, or be trained. Australian Shepherd, Bearded Collie, Belgian Malinois, Belgian Shepherd, Belgian Tervuren, Border Collie, Collie, German Shepherd Dog, Old English Sheepdog, Puli, Shetland Sheepdog.

Mixed breed dogs — the “love child” If knowing a dog’s breed allows you to predict a dog’s behavior, how can you assess the behavior of a mixed breed dog? Fortunately, based on research from the Jackson Laboratories in Bar Harbour, Maine, indicators suggest that form predicts function. It seems that data shows that a mixed breed dog is most likely to act like the breed that it most looks like. Thus, if a Labrador Retriever/Poodle cross looks much like a Labrador Retriever, it will probably act much like a Labrador Retriever. If it looks more like a Poodle, its behavior will be very Poodle-like. The more of a blend that the dog’s physical appearance seems to be, the more likely that the dog’s behavior will be a blend of the two parent breeds. |

Nonsporting dogs

The American Kennel Club originally had only two groups of dogs, sporting dogs and nonsporting dogs. The current AKC classification is much broader in scope. However, it still keeps this group as a sort of catchall for breeds it has problems classifying.

In our manuscript, we’ve chosen to eliminate this classification and sort these breeds into the preceding groups.

Predicting Behavior from Breed

Using the preceding 16 group classifications of dog breeds, we apply some scientific research out of the University of British Columbia that estimates that one half of the genetic makeup of any dog is genetically based.

In that study, 98 dog experts were surveyed and asked to rate the breeds on 22 aspects of their behavior. After much statistical analysis, it was found that, in reality, five important behavior dimensions existed, and systematic differences occurred among the various breed groups on these dimensions. The following sections look at these ratings to see how the different dog breeds stack up.

Intelligence and learning ability

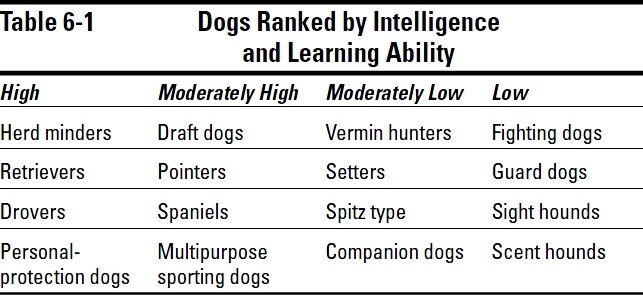

The first important dimension is a measure of how easily a dog learns and solves problems, which is generally what people mean by intelligence. It also indicates how easy it will be to teach the dog obedience commands and to perform service activities, which some dog experts refer to as trainability.

The experts list herding dogs and retrievers at the top of the list in intelligence, which probably explains why the top-ten lists of dogs in obedience competitions tend to be dominated by Border Collies, Shetland Sheepdogs, and Labrador and Golden Retrievers (see Table 6-1). It also probably explains why German Shepherds, Labrador Retrievers, and Golden Retrievers are frequently the preferred breeds for service dogs, guide dogs for the blind, and other complex tasks.

Warning!Though having a really smart dog may sound dreamy, it’s not. These dogs do best in highly structured, dog-savvy homes.

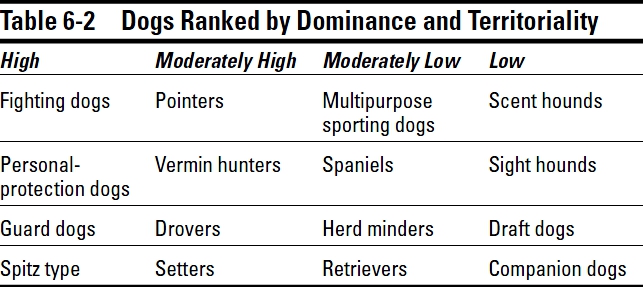

Dominance and territoriality

Think of this area as a measure of how “hard” or “soft” your dog is in its personality. It’s actually a measure of how assertive and possessive a dog is. The dogs that are high on this trait make good watch dogs and guard dogs (see Table 6-2). However, they may also be demanding, possessive, and pushy. They may guard their possessions, such as food and toys, vigorously. They’re also willing to use aggression against people and animals if it suits their purposes. Dogs low on this trait are unchallenging and nonthreatening.

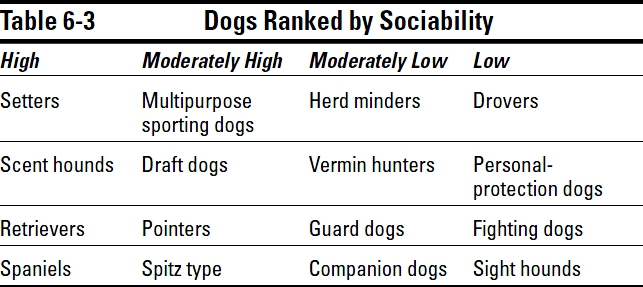

Sociability

This area refers to how friendly and agreeable a dog is. It reflects how much a dog seeks out companionship. A dog high on this trait happily greets any new person with its tail wagging (see Table 6-3). A dog low on this trait may appear shy and aloof and may frequently prefer to be alone rather than with people.

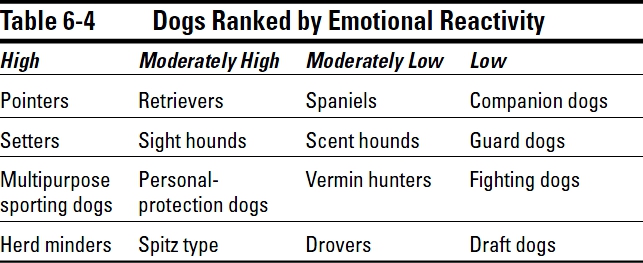

Emotional reactivity

This trait refers to the dog’s emotional state in the sense of how quickly its mood may change (see Table 6-4). Dogs high on this dimension are easy to excite but also calm down easily — their moods may rapidly fluctuate from confident to cautious and so on. A dog that is low on this trait may be much more difficult to excite, but once excited, it takes much longer to calm down.

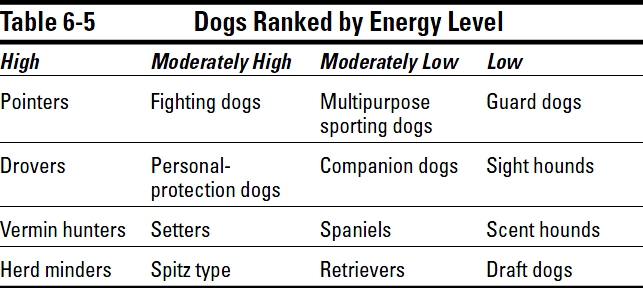

Energy level

This trait is actually a multifaceted measure that includes both indoor and outdoor activity level and the amount of force and energy the dog brings to common activities (see Table 6-5). A dog high on energy not only races around, but also may tug strongly on the leash or quickly and forcefully grab a treat from its owner’s hand.

Warning!Because experts feel that all breeds are capable of periods of high energy, even the lowest rankings aren’t truly inactive dogs.

by Stanley Coren and Sarah Hodgson