In This Chapter

- Choosing a veterinarian

- Knowing what to expect during your Boston’s veterinary visits

- Looking at vaccinations for common diseases

- Identifying internal and external parasites

- Getting your Boston spayed or neutered

As dapper and determined as they are, Bostons can’t take care of themselves, particularly when it comes to their health. One of the first things you need to do as a responsible dog owner is establish a relationship with a veterinarian you trust — someone with whom you feel comfortable asking questions, sharing concerns, and calling if the unthinkable happens. You and your Boston’s doctor will work together to ensure a long and healthy life for your beloved dog.

In this chapter, you figure out how to identify a qualified veterinarian. You find out what to expect during your Boston’s first veterinary visit, including the host of vaccinations your puppy will need. You also get the lowdown about those unpleasant internal and external parasites, like heartworm and fleas.

Finding a Vet for Your Pet

Your veterinarian’s job is to keep your Boston healthy and protected against disease. He will conduct annual screenings and suggest preventive care to ensure your Boston will live a long life. He will also vaccinate your Boston against common diseases, perform treatments as needed, prescribe remedies, and address any questions or concerns you may have. Next to you, the veterinarian will become your dog’s best friend.

Start looking for a veterinarian before your Boston becomes a part of your family. You should establish a doctor–patient–pet owner relationship as soon as possible, and that starts with identifying a veterinarian who’s right for you.

Getting referrals from trustworthy sources

You can begin your search for a veterinarian by contacting your local Boston Terrier club and asking for a recommendation (search

www.bostonterrierclubofamerica.org for the club nearest you). Chances are good that veterinarians suggested by club members have cared for many Boston Terriers. They understand the intricacies of the breed and can recommend specific treatments for your dog. Other than your local breed club, you can also get vet referrals from the following sources:

– Your breeder: If she lives in your area, she may be able to recommend a veterinarian; if she lives out of the area, she may know someone who lives in your city.

– Family, friends, and other dog owners: They can give firsthand reports of the vet’s bedside manner and expertise — and whether their pets approved of him!

– Veterinary associations: Groups such as the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) compile a list of member veterinarians whom they can recommend to you. The medical and management criteria for becoming an AAHA-approved clinic are strict, and a facility that meets these guidelines is often a cut above those that aren’t members.

– The phonebook and newspaper advertisements: These resources are helpful if you’re new to the area and don’t yet know your way around. Focus on those clinics that are near your home.

Remember

No matter where you find veterinary recommendations, always check them out before you decide who the best vet for your Boston is. If you find that you don’t like the veterinarian or the office staff, or you can’t communicate well with them, find another veterinarian. It’s okay to try out different doctors until you find one with whom you’re comfortable.

Figuring out who’s who in the vet world

Like medical doctors for people, veterinarians earn their doctorate degrees and go on to practice as a general practitioner. General practitioners maintain your Boston’s medical history, perform routine examinations and minor surgeries, and handle emergencies. A general practitioner is your Boston’s primary doctor.

Veterinarians can also practice in 1 of 20 American Veterinary Medical Association–recognized specialties, such as dermatology, ophthalmology, and internal medicine. These veterinary specialists, to whom your general practitioner will refer you if necessary, have focused their practice on specific areas of medicine.

Here, you can find out the differences between the general practitioners and veterinary specialists.

General practitioners

Veterinarians are licensed through the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). After completing four years in an AVMA–accredited veterinary school with one year dedicated to clinical rotations, they must pass rigorous federal and state board exams to earn their licenses — and the DVM (doctor of veterinary medicine) or VMD (veterinary medical doctor) after their names, depending on the traditions of the veterinary school that they attended.

General practitioners can perform many of the services your Boston will need, including annual checkups, vaccinations, minor surgeries, diagnostics, and prevention. If your Boston is sick, you will first take her to your general practitioner. But if she needs specialized care, your general practitioner will refer you to a specialist.

Veterinarians practice medicine in a variety of settings, from large veterinary hospitals that staff a number of doctors to privately owned clinics that have one or two doctors available. Some doctors work in franchise-like settings, while others practice medicine in teaching hospitals at veterinary schools.

Specialists

Veterinary specialists, such as veterinary behaviorists, surgeons, or dentists, undergo even more training than general practitioners do and choose to focus on a particular area of expertise.

Technical Stuff

To earn the title of veterinary specialist, the person must complete a standard veterinary school program and earn her DVM. Then, she must continue her education by completing a one-year internship and a two- to five-year residency program in her chosen discipline. After her educational requirements are complete, she must pass additional examinations to merit certification by a specialty board.

The certification requirements vary, but they are governed by the American Board of Veterinary Specialists, which has established guidelines on how veterinary specialists list their credentials. Veterinarians may not imply that they are specialists when they aren’t. If you’re seeking a veterinary specialist, look for terms like board certified and diplomate (often abbreviated as dipl.).

For example, this doctor specializes in veterinary nutrition: Sara Veterinarian, DVM, dipl. ACVN (American College of Veterinary Nutrition), board certified in clinical nutrition.

Remember

If your Boston requires the services of a veterinary specialist, your veterinarian will usually give you a referral.

Knowing what you’re looking for

Choosing the right veterinarian and clinic or hospital for your Boston depends on many criteria. Just as you would research your own physician, you’ll want to do the same with your dog’s veterinarian and animal hospital. To get started, ask yourself these questions:

- Is it important to find a veterinarian near my home?

- What services do I require from the clinic?

- What level of doctor–patient–pet owner familiarity do I want?

- Is a helpful office staff important to me?

The following sections can help you come up with answers that best suit you and your Boston.

Quality over convenience

Choosing a clinic near your home is certainly convenient. It will be much easier for you to show up for routine exams, grooming visits, and booster shots if your vet’s office is right down the road. The clinic’s office hours should also be compatible with your schedule. Ask if the doctors have early or late appointments and if they see patients on the weekend.

Remember

Don’t base your decision solely on convenience, however, because the nearest veterinarian may not be a good fit. You and your dog should feel comfortable with the doctor and his skills, and if you feel hesitant at all, find someone else. (See the upcoming section, “Interviewing your veterinarian,” for a list of questions to ask the potential veterinarian.)

Full range of services

Veterinary clinics offer a wide range of services, from grooming and boarding to ultrasounds and cancer treatment. Some practices even stock their shelves with retail products. Talk about one-stop shopping!

Before you select a clinic, jot down what services are important to you. If you plan to groom your own dog, for example, you may not need grooming services. Likewise, if you have a reliable dog sitter, you may not need boarding services.

You should definitely find out how the clinic handles emergencies. Some clinics have a staff veterinarian on call 24 hours a day, while others partner with nearby clinics or animal hospitals for afterhours emergencies.

You may also want to ask whether the clinic has a laboratory in the office or if it sends its lab work out. Talk to the vet or office manager about the length of time it takes to get lab results. You don’t want to be waiting for days to find out what exactly is wrong with your beloved Boston.

Also consider whether the clinic has access to specialty practitioners and services, like oncologists (vets who treat dogs suffering from cancer), dentists, or behaviorists. Most doctors can refer their clients to specialists, but you may want to have the services on-site.

One doctor versus whoever is available

In some clinics, you can see the same veterinarian each time you visit; in others, you may not have a choice. Practices maintain a history of your dog’s visits, including her immunizations, reactions to medications, and behavior traits, so from a treatment standpoint, you don’t have to see the same doctor each time.

But a strong doctor–patient–pet owner relationship plays a role in your dog’s overall health. By seeing the same vet every time, your Boston will become more comfortable with him, and the vet will really get to know your dog. Plus, seeing the same doctor each time may be important if your Boston has a recurrent or chronic problem.

Alternative treatmentsIn addition to traditional veterinary care, you can consider complementary and alternative health care for your Boston. Some of these alternatives include acupuncture, acupressure, massage, and chiropractic care. Acupuncture and acupressure are ancient Eastern therapies that consist of stimulating precise points on your dog’s body by inserting fine needles or applying pressure. Some veterinarians are specially trained in practicing this type of therapy. Massage and chiropractic therapy work the animal’s muscles and skeletal system to ease pain and speed healing. Before visiting any of these therapists, consult your traditional veterinarian for recommendations, advice, or further information. |

If you choose a sole practitioner for your Boston, be sure that another veterinarian can step in if your vet goes on vacation or is otherwise unavailable.

Helpful office staff

From the receptionist to the veterinary technician, the office staff’s attentiveness and quality affects the quality of your Boston’s care. The front office staff should be considerate and helpful. They greet you when you arrive and schedule follow-up appointments when you’re done. In smaller practices, they may assist the doctor in the exam room.

Veterinary technicians or veterinary assistants typically take your Boston’s temperature, weigh her, and take her vital signs before the vet comes into the exam room. Many times, they will explain the doctor’s diagnosis in terms that make sense to you.

Interviewing your veterinarian

After you’ve narrowed down your selections, you’ll want to find out more about the veterinarian. You may need to schedule a consultation or appointment to fit into the doctor’s schedule and pay a fee for the visit — but it will give you the opportunity to meet the office staff and talk to the veterinarian.

Ask the veterinarian candidate the following questions:

– How long have you been in practice?

– Have you cared for many Boston Terriers?

– What do you know about the Boston’s unique medical needs, temperament, and personality?

– What is your area of expertise? Do you specialize?

– Whom do you consult when presented with a medical problem that you’re not familiar with?

– Do you perform your own surgical procedures?

– Who monitors the dogs after surgery? Where are they cared for? _ How much veterinary education do you require your staff to have? Do they attend continuing education courses?

– How often do you attend veterinary conventions to learn about new medical procedures?

– Do you offer any alternative therapies?

Visit several clinics, if possible, and weigh the pros and cons of each. Remove from your list veterinarians who appear rude or use too much medical jargon when you ask questions. If a clinic appears dirty or smells offensive, or if the office staff is inattentive, take it off your list.

Instead, choose a veterinarian with whom you feel comfortable and who has a helpful office staff and top-notch service. When you find someone you think you can work with, schedule a routine physical for your dog as a first visit.

Your Boston’s First Vet Visit

Your veterinarian will want to see your Boston within 48 to 72 hours of arriving at her new home. Most breeders and rescue organizations require that you have your dog checked by a veterinarian soon after purchase or adoption to be sure she doesn’t have any health problems.

Tip

Arrive early to your appointment and bring the documents that came with your Boston. They contain important information the doctor needs, such as any vaccinations and tests already performed on your pet. Plan to fill out some preliminary paperwork that lists your dog’s vital statistics, activity level, previous health problems (if any), and other pets you may have. Also plan to bring a fresh stool sample so your veterinarian can check it for internal parasites.

You’ll likely be escorted to the exam room by a veterinary technician. These trained professionals will weigh your Boston, take her temperature, and ask questions about the reason for your visit.

During the physical exam, the veterinarian will conduct an overall health screening to look for potential health problems. She will listen to your pup’s heart and lungs; feel her abdomen, muscles, and joints; inspect her mouth, teeth, and gums; look into her eyes, ears, and nose; and look at your Boston’s coat. The veterinarian will look for anything out of the ordinary and watch the dog’s reaction when handled. The vet will also look for congenital problems, which are health problems an animal is born with.

After examining your dog and reviewing her medical records, your veterinarian may decide to vaccinate your Boston against a range of viruses and bacteria to which dogs are susceptible (see the next section). If your Boston already started her vaccinations, she may need booster shots.

Dirty businessDuring your Boston’s vet exam, you may need to bring a fresh stool sample so it can be examined for things like internal parasites. Collecting the sample isn’t as difficult — or disgusting — as it sounds. It needs to be fresh, so a few hours before your appointment, follow your dog outside with a sealable sandwich bag and a leftover food container with a tight-fitting lid. Turn the plastic bag inside out over your hand and pick up the fresh feces. The sample doesn’t need to be too large: A quarter-size amount of stool will do. Turn the plastic bag back around the sample, seal it, place it in the container, and close the lid. Label the container with your name, your dog’s name, and the date the sample was taken. And try not to get too grossed out! |

The veterinarian will ask you questions about the dog’s behavior. She will want to know your Boston’s eating and defecating habits and activity level. If you have witnessed anything out of the ordinary, be sure to tell the veterinarian.

Now is the time to ask any questions you may have, such as what and how much your Boston should be eating, any special health problems Bostons could have, and when your dog should be spayed or neutered. This is the time to establish a comfortable dialogue with your veterinarian.

Vaccinations: Protecting Your Dog from Deadly Diseases

Dogs face a range of communicable diseases today, but they can be prevented with vaccinations. Vaccines are essentially weakened or dead forms of a disease that are given to your Boston to stimulate her immune system, causing her to produce antibodies against that disease. When she’s exposed to the real disease, her body recognizes the invader, and her defenses fight it off.

When your Boston is a puppy, she gets antibodies from her mama’s milk. But starting at 6 weeks old and continuing every three to four weeks until your pup reaches 16 weeks old, your veterinarian will vaccinate your puppy against a range of diseases, which are detailed in the following section.

Knowing the diseases

Dogs are usually vaccinated against eight diseases. Whether your veterinarian inoculates against all of them depends on where you live and what viruses are prevalent. The rabies vaccine, for example, is mandated by state law, but if coronavirus isn’t a problem in your region, your vet won’t give your Boston that vaccine. Also, if you travel or are planning to travel with your dog, be sure to let your vet know so he can vaccinate appropriately.

Here are the eight diseases your pup will be vaccinated for, and how they can affect your pup:

– Distemper: Distemper is a contagious viral disease that causes symptoms resembling a bad cold with a fever. It can include runny nose and eyes, and an upset stomach that can lead to vomiting and diarrhea. Many infected animals exhibit neurological symptoms, which may include involuntary twitching, paralysis, and convulsions. An incurable and deadly disease, distemper is passed through exposure to the saliva, urine, and feces of raccoons, foxes, wolves, mink, and other dogs already infected with the virus. Unvaccinated young pups and senior dogs are most vulnerable to distemper. Any pup or dog who has received a distemper vaccination prior to exposure to the virus is unlikely to become infected.

– Hepatitis: Spread through contact with other dogs’ saliva, mucus, urine, or feces, hepatitis affects the liver. It causes apathy, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, and jaundice. The mortality rate is high, but vaccination prevents the disease.

– Leptospirosis: A highly contagious bacteria that is passed through the urine of infected dogs, rats, farm animals, and wildlife, leptospirosis attacks the dog’s kidneys, causing kidney failure. Symptoms include fever, appetite loss, possible diarrhea, and jaundice. Vaccinations usually prevent the disease, though the bacteria does appear in different forms, and the vaccine may not protect against all of them. Lepto is a zoonotic disease, which means that it can spread to humans.

– Parvovirus: Another deadly virus, parvo is transmitted by direct contact with infected dogs and their feces. The virus attacks the inner lining of a dog’s intestines and causes bloody diarrhea. Symptoms also include fever, lethargy, appetite loss, vomiting, and collapse. Because this virus replicates very quickly, your Boston needs prompt medical attention if she exhibits any of these signs. The vaccination is usually effective at preventing the virus if given at proper intervals during the first 6 to 16 weeks of life.

– Kennel cough: Adenovirus, parainfluenza, and bordetella all refer to a condition known as infectious tracheobronchitis, or kennel cough. They are rarely deadly, but they do cause significant coughing, sneezing, and hacking, sometimes with nasal discharge and fever. Severe cases may progress to pneumonia. Symptoms may last from several days to several weeks. This very contagious virus spreads when the sick dog coughs and expels airborne mucous. Some forms of the virus cannot be vaccinated against. Dogs who frequent kennels, training classes, groomers, dog parks, or other public facilities should be vaccinated routinely.

– Rabies: Carried in the saliva of infected wildlife and transmitted through bites or cuts, rabies attacks the nerve tissue and causes paralysis and death. It’s always fatal to unvaccinated animals and people. In most areas, proof of rabies vaccination is required when you apply for a dog license. Some states require yearly rabies vaccinations, while others allow vaccinations every three years. Rabies is a zoonotic disease, which means people can become infected by the saliva of a rabid animal.

– Coronavirus: Rarely fatal for puppies and adult dogs, coronavirus causes a loose, watery stool and vomiting. Dehydration from the diarrhea and vomiting endangers puppies. The virus is spread through the stool.

– Lyme disease: Lyme borreliosis, or Lyme disease, is caused by a bacterium that can make animals and humans sick. Spread by hard-bodied ticks that bite an infected animal and then bite another animal, the disease causes a range of symptoms, including lameness, swollen joints, fever, appetite loss, and lethargy. In the United States, it is most common around the Atlantic seaboard, upper Midwest, and Pacific coast, though it does occur throughout the country.

Following the vaccination schedule

If you’re intimidated by the diseases that can affect your Boston and the number of vaccines needed to prevent them, rest easy. Your veterinarian can help you schedule all the shots your puppy needs.

Typically, at 6 to 8 weeks old, your vet will vaccinate your puppy for the most common diseases — distemper, hepatitis, leptospirosis, parvovirus, and parainfluenza — in one combined injection, called DHLPP. Your Boston will get another shot at 10 to 12 weeks old, and a third at 14 to 16 weeks old.

Your puppy receives her first rabies vaccine at 12 weeks old and her second vaccine a year later. Depending on the laws in your state, your dog may also require a vaccination later on.

Coronavirus and Lyme disease vaccinations are given only if there is a problem in your area. Your vet will administer these vaccines at the same time as her first two DHLPP injections, at 6 to 8 weeks old, and again at 10 to 12 weeks old.

Depending on the vaccine, your vet will give the injection into a muscle or under the skin. Some vaccines for kennel cough are given through the nose. Most times, your puppy won’t be fazed by the vaccinations, and she’ll be bounding around your home in no time.

Remember

After your puppy has completed her vaccinations, you’ll need to take her to the veterinarian for booster shots once a year.

Technical Stuff

Based on recent research that suggests yearly booster shots may be damaging to dogs’ immune systems, booster protocols are changing. Some veterinarians give boosters every 18 months, while some veterinary schools recommend that they can be given every 36 months. Talk to your veterinarian about his suggested booster schedule and whether he is concerned about the frequency of booster shots.

Patrolling for Parasites

Vaccinations prevent certain viruses and bacteria from afflicting your Boston, but she is still susceptible to other medical problems, including internal and external parasites.

Parasites are tiny organisms that live off of another living organism. These little thieves come in all shapes and sizes, from single-celled protozoa and small fleas to long intestinal tapeworms. There are two types of parasites: internal and external. They latch onto the host animal and draw nourishment from her without providing any benefit in return. Sometimes, the parasites weaken the host (your dog) so severely that they can cause death.

In most cases, your Boston will pick up parasites from exposure to contaminated environments. For example, your dog may romp through a grassy field and bring home some fleas or ticks, or she may ingest a strange dog’s feces and develop an internal parasite.

Tip

Generally, you can prevent parasites by limiting your dog’s exposure to other animals’ urine and feces, giving her a heartworm preventive every month (as prescribed by your veterinarian), and applying a flea-and-tick repellant to her coat (also available through your veterinarian).

In the sections below, I detail the most common internal and external parasites, and how you can prevent your Boston from bringing home these troublesome hitchhikers.

Internal parasites: The worms

Internal parasites are a part of pet ownership. They aren’t pleasant, but you need to address them to keep your pet healthy. Because these pests live inside your Boston, you can’t see the damage they’re causing! It can take quite some time before your dog exhibits external signs of an internal parasite problem.

Your veterinarian can detect most internal parasites through testing and microscopic examinations. A stool sample often contains the eggs, dead remains of the parasite, or even the larvae. Your vet will prescribe a treatment, and after it runs its course, you will need to bring in another stool sample to be sure the treatment worked.

Several types of internal parasites affect dogs. Some are more destructive than others. The following are the most common.

Hookworm

Hookworms, which can cause fatal anemia in puppies, attach themselves to the small intestine and suck the dog’s blood. After detaching and moving to a new location, the wound continues to bleed, causing bloody diarrhea — often a sign of a hookworm infestation. Like other internal parasites, hookworm eggs are passed through the stool, so good sanitation prevents their spread. Humans can also suffer from hookworms.

Hookworm treatment involves feeding the dog an oral deworming tablet or liquid and giving her another dose one month later. The first treatment destroys the adult worms living in dog, and the second treatment destroys the next generation. After the second treatment, your vet will do another fecal exam to be sure the parasites are gone.

Roundworm

Roundworms, which are long white worms that live in the dog’s intestines, are fairly common in puppies. They can be seen in feces and vomit, and the eggs are transmitted through the stool. A dog infested with roundworms is thin and may have a dull coat and potbelly. A stool analysis will confirm diagnosis. Good sanitation will prevent the spread of roundworm.

As with hookworm infestations, treatment involves feeding the dog an oral deworming medication and repeating it several times to ensure subsequent generations of the parasite are destroyed.

Warning!

Roundworms are also a zoonotic disease that can cause neurological damage and blindness in humans. Small children are at high risk for becoming infected.

Whipworm

This internal parasite lives in the large intestine where it feeds on blood. A heavy infestation of whipworms can be fatal to adults and puppies because it can cause severe diarrhea. Dogs infested with whipworm look lethargic and thin. Whipworm eggs are passed in the feces and can live in the soil for years, so dogs who dig or eat grass can pick up eggs.

If caught early, whipworm can be treated with deworming medications that must be administered over extended periods of time. Because of the long maturation cycle of young worms, a second deworming is needed 75 days after the first one. Additional doses may be necessary, as well.

Heartworm

A dangerous yet preventable parasite, heartworms live in an infected dog’s upper heart and arteries, damaging its blood vessel walls. Poor circulation ultimately causes heart failure. The parasite is spread by mosquitoes. Adult heartworms produce tiny worms, which circulate throughout the dog’s bloodstream. When a mosquito bites a dog, the mosquito picks up the worms and transmits them to another dog.

The first signs of heartworm include breathing difficulty, coughing, and lack of energy, though some dogs show no signs until it’s too late. To confirm a diagnosis, your vet will take a blood test to look for worms. He may also do an X-ray. If the test results are positive, your vet will give your dog medication to kill the worms.

Preventive medications, however, are the best remedy. They are easily available, and they’re very effective. If heartworm is prevalent in your area, your veterinarian will first do a blood test to determine whether your dog is infected if your dog is over 6 months old. Puppies under 6 months can be started on prevention without testing. After a clean bill of health, your veterinarian will prescribe preventive heartworm medication. Many of these medications also provide a monthly deworming for roundworms, hookworms, and whipworms.

Giardiasis

Commonly passed through wild animals, giardia, an intestinal parasitic protozoon, affects humans and animals and causes diarrhea and lethargy. It’s often found in mountain streams, but it can also be found in puddles or stagnant water. Your veterinarian will test for giardiasis and can prescribe treatment, which consists of giving your pet an oral antibiotic.

Tapeworms

Spread by infected fleas or from eating rabbit entrails, tapeworms live in an animal’s intestine, attach to the wall, and absorb nutrients. They grow by creating new segments, which can often be seen around the dog’s rectum or in her stool as small rice-like pieces.

Your veterinarian can treat the tapeworm by prescribing tablets or giving your dog a series of injections, but a good flea-control program is the best prevention against tapeworm infestation.

External parasites: Pesky critters

Fleas and ticks (and other bothersome bugs) are not fun on your dog — or in your house! These parasites live off your pet’s blood. They spread disease, including tapeworms (an internal parasite) and Lyme disease.

Fleas are small, but they’re not invisible. If you see just one flea crawling on your Boston or hopping in your carpet, for example, chances are very high that there are many more. You may see your pup scratching and biting to rid herself of the parasites, or you may see her rolling on the floor to ease the discomfort. When combing through your dog’s coat, you may also see white flea eggs or their “dirt,” which can resemble specks of pepper.

Ticks look like brown or black sesame seeds with eight legs. They won’t overrun your home like fleas can, but they will cause misery as they suck your pup’s blood. Ticks prefer the area around your dog’s head, neck, ears, and feet, and in the warm areas between her legs and body.

If your pup is scratching but you’ve found no signs of fleas, she may have mange mites. These microscopic marauders like the areas around the elbows, hocks, ears, and face. They will need to be identified by your veterinarian, who will scrape your pup’s skin and inspect it under the microscope.

Thankfully, these pests can be controlled so you and your Boston can enjoy the great outdoors together, where these critters are commonly found.

Fleas

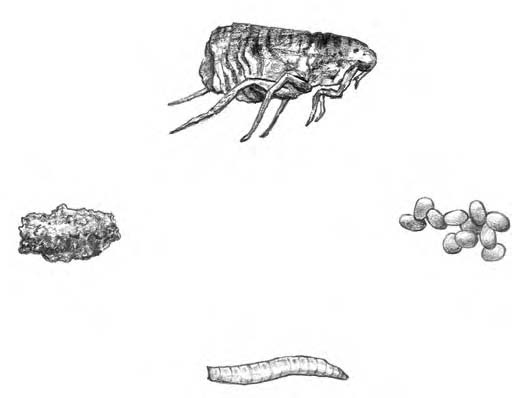

Fleas are small, crescent-shaped insects that suck the blood from your Boston (see Figure 14-1). With their six legs and huge abdomen, they can jump surprisingly far in proportion to their size. Their bite causes allergic reactions in dogs and their humans, causing itching, discomfort, and misery!

In large numbers — especially on a little dog like your Boston — fleas can cause anemia and severe allergic reactions that can lead to open sores and possibly a secondary infection.

Figure 14-1: Fleas pass through four phases, shown above, as they complete their life cycle. One female flea lays about 20 eggs per day and up to 600 in her lifetime.

Fleas also spread internal parasites, such as tapeworms. When a dog swallows a tapeworm-infected flea, she then becomes infested with tapeworm. In the past, fleas carried bubonic plague. These parasites are a more than a nuisance — they are a real threat.

Luckily for your Boston, more flea-control options exist now than ever before.

– Topical treatments: These treatments are applied to the pup’s skin between the shoulder blades. The product is absorbed through the dog’s skin into her system. The flea is killed when it bites the animal or when its reproduction cycle is altered.

Warning!

Different topical flea-control formulas have different active ingredients, and the directions for one may differ from another. Ask your veterinarian which product is right for your dog and how the product should be applied.

– Systemic treatments: These treatments include pills that the dog swallows. When the flea bites the dog, the chemical in the pill is transmitted to the flea, which (depending on the product) either prevents the flea’s eggs from developing or kills the adult fleas, so the population dies off.

– Insect growth regulators (IGRs): IGRs stop immature fleas from maturing and prevent them from reproducing, so the population ceases to exist. Dispensed as foggers, sprays, and in discs, IGRs can be used in the environment to stop bug populations from thriving.

In addition to treating your Boston, you also need to treat your house and the shady areas of your yard for complete flea eradication. The fleas will return if any one of the three is neglected. Treat both the yard and the house with a spray that contains an IGR.

If you prefer a natural external parasite control, several plantbased flea-control products are available over the counter. Some of the more popular ones include pyrethrins, which are derived from chrysanthemums, and citrus-based derivatives. They both work to knock down the flea population, but they do little to eradicate an infestation.

Ticks

Ticks are eight-legged bloodsuckers that latch on, embed their head into your pet’s skin, and suck until they become engorged with blood.

Like fleas, ticks carry blood-transmitted diseases, including Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Lyme disease is characterized by a lingering fever, joint pain, and neurological problems. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is characterized by muscle pain, high fever, and skin sores.

Some flea-control products also deter ticks, but the best thing to do is check your Boston after romps in tick-infested areas. During the spring and summer, inspect your dog daily, paying close attention to the areas behind her ears, in the armpit area under her front legs, and around her neck.

If you find a tick on your pet, you should remove it. Here’s how:

1. Use tweezers to grab hold of the tick as close to the skin as possible.

2. Pull gently but firmly with a twisting motion. Dip the critter in alcohol or flush it down the toilet so it can’t crawl back.

3. Put a little antibiotic ointment on the wound where the tick was embedded.

Mange mites

Mange, or microscopic skin mites, causes your dog’s skin to swell and form itchy, pus-filled scabs. The disease comes in two varieties: sarcoptic mange, which is contagious to people and other pets, and demodectic mange, which is not contagious. Your veterinarian will do a skin scraping to determine which variety is plaguing your dog.

Dogs suffering from mange mites may scratch themselves fiercely. Patches of skin look red and scaly, and they may have areas of thinning hair around their eyes, mouth, and the fronts of their legs. In more advanced infestations, crusty sores form and ooze, which may lead to secondary infections. Treatment involves bathing in medicated shampoos, and possibly antibiotics or steroids to relieve the itching symptoms, and ivermectin injections or oral solution. The heartworm prevention Revolution can also be used to treat sarcoptic mange.

Ringworm

Ringworm isn’t a parasite at all. It’s a contagious fungus that infects the skin and causes a red, ring-shaped, itchy rash. It spreads by contact from other animals. Ringworm responds well to treatment, but because it’s so contagious to people and other animals, the plan must be followed diligently to eradicate the fungus.

Treatment for ringworm involves a three-pronged approach:

– Giving your Boston a pill that stops the fungus from growing

– Cleaning the affected area thoroughly and frequently with iodine to kill the fungus on your pet

– Keeping your environment clean using antifungal solutions, such as a 1-to-20 bleach-to-water ratio

To Spay or Neuter

Having your Boston fixed means having her spayed (or him neutered), or rendering the dog unable to produce baby Bostons. It may seem cruel and unusual, but the routine procedure is one of the best things you can do for your dog’s health and happiness. The surgery prevents certain diseases, like uterine and testicular cancer, and it mellows out your Boston’s mood.

Remember

Spaying or neutering your Boston doesn’t cause personality changes, but it does result in some positive behavioral changes. Dogs who are spayed or neutered

- Exhibit less aggressive behavior than those who don’t have surgery

- Are less likely to roam in search for a mate

- Are less likely to mark with urine or soil rugs and furniture

Most importantly, spaying or neutering your pet helps control the pet overpopulation problem plaguing our country today. Countless puppies find themselves relinquished to shelters because their owners couldn’t find homes for them.

Growing up fast: Your Boston’s sexual maturity

Dogs reach sexual maturity between the ages of 6 to 9 months old, at which time they are capable of reproducing. Their voices don’t start to crack, but their hormones begin to activate, and their behavior starts to change.

Most females have their first estrus, or heat, cycle when they reach 6 months of age. The cycle, or season, begins with proestrus, which is when she bleeds. It can last up to 15 days, and it marks the beginning of the estrus cycle.

During the estrus cycle, the female is the most fertile and will emit a pheromone that makes her more attractive to males. She may even flirt and lift her rear in the air while wagging her tail back and forth! Her behavior may also change. She may seem hyperactive or stressed. The cycle typically lasts 21 to 30 days, though each dog’s cycle differs. Female dogs are in season two times per year.

After a male dog reaches maturity, he can breed with a female in heat at any time. If he’s not neutered, he’ll constantly sniff the air in search of a female in season. He’ll also mark his territory by lifting his leg and leaving behind his scent. Male dogs may also grasp pillows or unsuspecting human legs and hump them!

Understanding the surgical procedures

Living with an unspayed female or intact male can certainly be a challenge for you (for specifics, see the previous section). It’s no fun for the dogs, either, unless they’re allowed to breed freely. But that’s where spay or neuter surgery can make life with your Boston pleasurable again.

Your veterinarian can perform a routine operation on your dog under general anesthesia when he or she is about 6 months old, or just before sexual maturity. Your Boston will feel no pain at all during the surgery and a minimal amount after the surgery while he or she recovers:

– Females are spayed. This process involves an ovariohysterectomy, where the ovaries and uterus are removed surgically. Your Boston will be out of sorts for a few days, but she’ll be back to her old self in no time. Not only does this procedure prevent unwanted puppies, but it also protects her from uterine infection, ovarian cancer, and mammary gland cancer, and prevents heat cycles.

– Males are neutered. Their testicles are removed through a small incision just in front of the scrotum. Like the female, the male will be less social for a few days, but he’ll quickly be back to normal. An added benefit of neutering includes protection from testicular cancer and reduced risk of prostate infections.

Remember

In some cases, you can take your pup home after he or she has recovered from the surgery. In most cases, however, be prepared to leave your Boston overnight so the staff can make sure that everything went okay.

Making Annual Visits

The first visit to the veterinarian is just the beginning of many regular appointments to come for your Boston. Annual visits, just like annual checkups for you, are a preventive step that ensures your Boston’s continued good health. These appointments allow the veterinarian to catch problems early before they turn into lifethreatening situations.

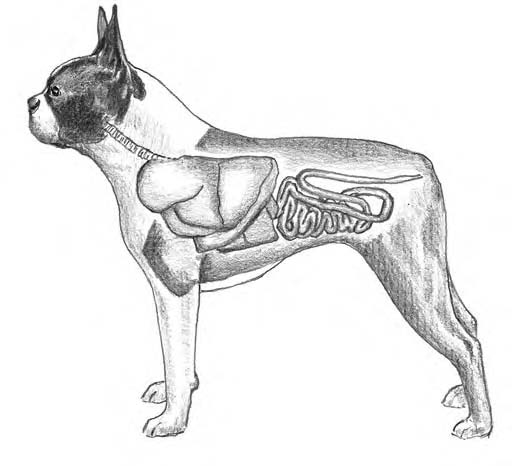

During an annual exam, your veterinarian will conduct an exam similar to your Boston’s first visit. He will examine your dog’s overall health, check for any changes, and ask you questions about her behavior. Your vet will check your dog’s vital organs and look at her eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, as well as feeling her body for tumors or sore spots (see Figure 14-2).

Your veterinarian may also ask you questions like these:

- How long have you had your Boston Terrier?

- When was the last time you took her to the veterinarian?

- Are you having any problems with her training?

- Do you plan to neuter (or spay) your dog (if it hasn’t already been done)?

- How many hours a day do you spend with your Boston?

- What types of activities do you enjoy doing with your dog?

- Do you notice any problems with her eating or eliminating?

- Is she drinking more than usual?

- Do you use a crate? How is her housetraining coming along?

- Have you noticed any signs of illness, such as lethargy, loose stools, poor appetite, excessive sneezing or coughing, or any discharge from her eyes, nose, or ears?

- What are you feeding your dog? How much?

- Does your dog display any troublesome behavior?

If everything checks out, you won’t need to visit the veterinarian again for another year. But if something looks amiss, your vet may recommend laboratory work or X-rays. The office will call with test results as soon as they’re available.

Remember

With your veterinarian’s help, you can keep your Boston Terrier healthy and strong for her lifetime. Disease prevention, annual veterinary exams, and regular checks of your dog for physiological or neurological changes will hopefully catch problems before they become serious.

Figure 14-2: A Boston Terrier’s anatomy.

by Wendy Bedwell-Wilson