- Crate-training your dog

- Setting up an elimination schedule and other fundamentals of housetraining

- Exploring an alternative to crate-training

- Understanding why your dog marks his territory

- Taking your dog for a ride

The well-trained dog’s education begins with housetraining. As with any training, some dogs catch on more readily than others. Some of the toy breeds are notoriously dense in this regard and vigorously resist all efforts requiring their cooperation.

As a general rule, however, the majority of dogs don’t present a problem, provided you do your part. To speed along the process, we strongly recommend that you use a crate or similar means of confinement.

Initially, you may recoil from this concept as cruel and inhumane. Nothing could be farther from the truth. You’ll discover that your puppy likes his crate and that you can enjoy your peace of mind.

Using a Crate: A Playpen for Your Puppy

When Jim and Laura went to pick up their puppy, the breeder asked them what they thought was a peculiar question. “When you were raising your children, did you use a playpen?” “Of course,” said Laura, “I don’t know what I would have done without it.” “Fine,” said the breeder, “a crate for a puppy is like a playpen for a child.”

Whatever your views on playpens, dogs like crates. A crate reminds them of a den — a place of comfort, safety, security, and warmth. (See Figure 4-1.)

Figure 4-1: In addition to helping with housetraining, a crate is a comfy den for your dog.

Puppies, and many adult dogs, sleep most of the day, and many prefer the comfort of their den. For your mental health, as well as that of your puppy, get a crate.

Here are just a few of the many advantages to crate-training your dog:

– A crate is a babysitter — when you’re busy and can’t keep an eye on your dog, but want to make sure he doesn’t get into trouble, put him in his crate. You can relax, and so can he.

– Using a crate is ideal for getting him on a schedule for housetraining.

– Few dogs are fortunate enough to go through life without ever having to be hospitalized. Your dog’s private room at the veterinary hospital will consist of a crate. His first experience with a crate shouldn’t come at a time when he’s sick — the added stress from being crated for the first time can retard his recovery.

– A crate is especially helpful during the times when you have to keep your dog quiet, such as after being altered or after an injury.

– Driving any distance, even around the block, with your dog loose in the car is tempting fate. Stop suddenly and who knows what could happen. Having the dog in a crate protects you and your dog.

– When we go on vacation, we like to take our dog. His crate is his home away from home, and we can leave him in a hotel room knowing he won’t be unhappy or stressed, and he won’t tear up the room.

– A crate is a place where he can get away from the hustle-and-bustle of family life and hide out when the kids become too much for him.

Remember

A crate provides a dog with his own special place. It’s cozy, secure, and his place to go to get away from it all. Make sure your dog’s crate is available to him when he wants to nap or take some time out. He’ll use it on his own, so make sure he always has access to it. Depending on where it is, your dog will spend much of his sleeping time in his crate.

Finding the right crate

Select a crate that’s large enough for your dog to turn around, stand up, or lie down comfortably. If he’s a puppy, get a crate for the adult size dog so that he can grow into it.

Some crates are better than others in strength and ease of assembly. You can get crates in wire mesh-type material, cloth mesh, or plastic (called airline crates). Most are designed for portability and are easy to assemble. Our own preference for durability and versatility is a wire mesh crate. Wire mesh crates are easy to collapse, although they’re heavier than crates made out of cloth mesh or plastic.

Remember

We recommend a good-quality crate that collapses easily and is portable so that you can take it with you when traveling with your dog. If you frequently take your dog with you in the car, consider getting two crates, one for the house and one for the car. Doing so saves you from having to lug one back and forth.

Coaxing Buddy into the crate

In order to coax Buddy into the crate, use these helpful hints:

1. Set up the crate and let your dog investigate it.

Put a crate pad or blanket in the crate.

2. Choose a command, such as “Crate” or “Go to bed.”

If your puppy isn’t lured in, physically place Buddy in the crate, using the command you’ve chosen.

3. Close the door, tell him what a great puppy he is, give him a bite-sized treat, and then let him out.

There’s no rule against gentle persuasion to get your pup enthused about his crate.

4. Use a treat to coax him into the crate.

If he doesn’t follow the treat, physically place him in the crate and then give him the treat.

5. Again, close the door, tell him what a great little puppy he is, and give him a bite-sized treat.

6. Let him out.

The treat doesn’t have to be a dog biscuit so long as it’s an object the dog will actively work for.

7. Continue using the command and giving Buddy a treat after he’s in the crate until he goes into the crate with almost no help from you.

Tip

For the puppy that’s afraid of the crate, use his meals to overcome his fear. First, let him eat his meal in front of the crate, and then place his next meal just inside the crate. Put each successive meal a little farther into the crate until he’s completely inside and no longer reluctant to enter.

Helping Buddy get used to the crate

Tell your dog to go into the crate, give him a treat, close the door, tell him what a good puppy he is, and then let him out again. Each time you do this, leave him in the crate a little longer with the door closed, still giving him a treat and telling him how great he is.

Finally, put him in his crate, give him a treat, and then leave the room — first for 5 minutes, and then 10 minutes, and then 15 minutes, and so on. Each time you return to let him out, tell him how good he was before you open the door.

How long can you ultimately leave your dog in his crate unattended? That depends on your dog and your schedule, but for an adult dog, don’t let it be more than eight hours.

Warning!

Never use your dog’s crate as a form of punishment. If you do, he’ll begin to dislike the crate, and it will lose its usefulness to you. You don’t want Buddy to develop negative feelings about his crate. You want him to like his private den.

Identifying the Fundamentals of Housetraining Your Puppy

The keys to successful housetraining are

- Crate-training your puppy first.

- Setting a schedule for feeding and exercising your dog.

- Sticking to that schedule, even on weekends — at least until your dog is housetrained and mature.

- Vigilance, vigilance, and vigilance until your dog is trained.

Using a crate to housetrain your puppy is the most humane and effective way to get the job done. It’s also the easiest way because of the dog’s natural desire to keep his den clean. The crate, combined with a strict schedule and vigilance on your part, ensures speedy success (see “Using a Crate: A Playpen for Your Puppy” earlier in this chapter for tips on crate-training your puppy).

Remember

Over the course of a 24-hour period, puppies have to eliminate more frequently than adult dogs. A puppy’s ability to control elimination increases with age, at approximately the rate of one hour per month. During the day, when active, the puppy can last for only short periods. Until he is 6 months of age, expecting him to last for more than four hours during the day without having to eliminate is unrealistic. When sleeping, most puppies can last through the night. If you have a female puppy and you notice frequent accidents (urine), it could be a sign of a bladder infection called cystitis, which requires a trip to the vet.

Set up an elimination schedule

Dogs thrive on a regular routine. By feeding and exercising Buddy at about the same time every day, he’ll also relieve himself at about the same time every day.

Tip

Set a time to feed the puppy that’s convenient for you. Always feed at the same time. Until he’s 4 months of age, he needs four meals a day; from 4 to 7 months, three daily meals are appropriate. From then on, feed twice a day, which is healthier than feeding only once and helps with housetraining.

A sample feeding schedule follows:

- 7 weeks through 4 months — four times a day

- 4 months to 7 months — three times a day

- 7 months on — two times a day

Remember

Feed the right amount — loose stools are a sign of overfeeding; straining or dry stools a sign of underfeeding. After ten minutes, pick up the dish and put it away. Don’t have food available at other times. Keep the diet constant. Abrupt changes of food may cause digestive upsets that won’t help your housetraining efforts. (For tips on how often and how much to feed, look in Chapter Feeding Your Dog.)

For the sake of convenience, you may be tempted to put your puppy’s meal in a large bowl and leave it for him to nibble as he sees fit, called self-feeding. Although convenient, for purposes of housetraining, don’t do it because you won’t be able to keep track of when and how much he eats. You won’t be able to time the in with the out.

Fresh water must be available to your dog at all times during the day. When left in his crate for more than two hours, leave him a dish of fresh water in the crate. You can also attach a little water bucket to the inside of the crate. After 8 p.m., remove his water dish so he can last through the night. If you work all day and are unable to follow this schedule, see the section, “Using an Exercise Pen for Housetraining” later in this chapter.

Remember

A strict schedule for your dog is a great asset in housetraining. If you feed your dog and take him out for exercise at the same times every day, he’ll tend to eliminate at the same times every day. After you and your dog have established a schedule, you can project when he’ll need to relieve himself and help him to be in the right spot at the right time.

Establish a regular toilet area

Start by selecting a toilet area and always take Buddy to that spot when you want him to eliminate. If possible, pick a place in a straight line from the house. Carry your puppy or put him on leash. Stand still and let him concentrate on what he’s doing. Be patient and let him sniff around. After he’s done, tell him what a clever puppy he is and play with him for a few minutes. Don’t take him directly back inside so that he doesn’t get the idea that he only gets to go outside to do his business and learns to delay the process just to stay outside.

Remember

Witnessing the act of your puppy relieving himself outside, followed by playtime, is perhaps one of the most important facets of housetraining. The first sign of not spending enough time outside with your puppy is when he comes back inside and has an accident. Letting the puppy out by himself isn’t good enough — you have to go with him until his schedule has been developed.

Where you live will dictate your housetraining strategies. In a city, where dogs have to be curbed to relieve themselves, you need to keep Buddy on leash. You also need to pick up after him, please! If you walk your dog in a park or through a neighborhood, you also need to pick up after him. Don’t let him do his business in a neighbor’s yard — not even in the yard of that old crotchety neighbor who yelled at your children.

Even in your own yard, unless you have oodles of land, you need to pick up after him for sanitary reasons. If you have a fenced yard and don’t mind where he goes, you can let him off leash. If you want him kept to a particular spot, keep him on leash and then clean up.

You may also want to teach Buddy a command, such as “Hurry up,” so that you can speed up the process when necessary. Time the command to just before he starts and then lavishly praise when he has finished. After several repetitions, Buddy will associate the command with having to eliminate.

Keep your eyes open for signs

Take your puppy to his toilet area after waking up, shortly after eating or drinking, and after he has played or chewed. A sign that he has to go out is sniffing the ground in a circling motion.

Success Story

Setting up a housetraining scheduleFirst thing in the morning, Mary takes her 12-week-old poodle puppy, Colette, out of her crate and straight outside to her toilet area. Fifteen minutes after Colette’s morning meal, she’s let out again. Mary then crates Colette and leaves for work. On her lunch break, Mary goes home to let Colette out to relieve herself, and she plays with her for a few minutes. She then feeds her and, just to make sure, takes her out once more. For the afternoon, Colette is crated again until Mary returns. Colette is then walked and fed, after which she spends the rest of the evening in the house where Mary can keep an eye on her. Before bedtime, Colette goes out to her toilet area one more time and is then crated for the night. When Colette becomes 7 months old, Mary will drop the noontime feeding and walk. From that age on, most dogs only need to go out immediately or soon after waking up in the morning, once during the late afternoon, and once again before bedtime. |

When you see your puppy sniffing and circling, take note! He’s letting you know that he’s looking for a place to go. Take him out to his toilet area so he doesn’t make a mistake.

Tip

Special care is required when it’s raining or is very cold because many dogs, particularly those with short hair, don’t like to go out in the wet anymore than you do. Make sure the puppy actually eliminates before you bring him back into the house.

An accident is an accident is an accident

No matter how conscientious and vigilant you are, your puppy will have an accident. Housetraining accidents may be simple mistakes, or they can be indicative of a physical problem. The key to remember is that, as a general rule, dogs want to be clean.

Warning!

When Buddy has had an accident in the house, don’t call him to you to punish him. It’s too late. If you do punish your dog under these circumstances, it won’t help your housetraining efforts, and you’ll make him wary of wanting to come to you.

A popular misconception is that the dog knows “what he did” because he looks “guilty.” Absolutely not so! He has that look because from prior experience he knows that when you happen to come across a mess, you get mad at him. He has learned to associate a mess with your response. He hasn’t and can’t make the connection between having made the mess in the first place and your anger. Discipline after the fact is the quickest way to undermine the relationship you’re trying to build with your dog.

Dogs are smart, but they don’t think in terms of cause and effect. When you come home from work and yell at your dog for having an accident in the living room, you aren’t encouraging your dog to use his toilet area. All you’re doing is letting him know that sometimes you’re really nice and sometimes you’re really mean. Swatting your dog with a rolled-up newspaper is cruel and only makes him afraid of you and rolled-up newspapers. Rubbing his nose in it is unsanitary and disgusting. Dogs may become housetrained in spite of such antics, but certainly not because of them.

Tip

When you come upon an accident, always keep calm. Put your dog out of sight so he can’t watch you clean up. Use white vinegar or a stain remover. Don’t use any ammonia-based cleaners, because the ammonia doesn’t neutralize the odor and the puppy will be attracted to the same spot.

Remember

Accidents are just that — accidents. The worst thing you can do is call your dog to you to punish him. Your dog didn’t do it on purpose, and most dogs are just as horrified by what happened as you are.

Be ready for regressions

Regressions in housetraining do occur, especially during teething. Regressions after 6 months of age may be a sign that your dog is ill. If accidents persist, take him to your vet for a checkup.

What to do if you catch Buddy in the act

Tip

If you catch your dog in the act, sharply call his name and clap your hands. If he stops, take him to his toilet area. If he doesn’t, let him finish and don’t get mad. Don’t try to drag him out because that will make your clean-up job that much more difficult. Until your puppy is reliable, don’t let him have the run of the house unsupervised.

How to train an adult dog

If you’ve obtained an adult dog from a shelter or other source, he may not be housetrained. For example, if he was tied on a chain outside, he most certainly won’t be.

The rules for housetraining an adult dog are the same as for a puppy, but the process should go much more quickly. The adult dog’s ability to control elimination is obviously much better than a puppy’s.

What to do about an apartment dog

Many dogs live in apartments, and their owners have to jump through a variety of hoops to get their dogs outside, such as elevators, stairs, and so on. Moreover, if the owner is mobility impaired, taking the dog outside may be a real challenge.

Presumably, an apartment dog is a small dog. In any event, the easiest way to housetrain an apartment dog is to first follow the regimen by using a crate, and after that by using an X-pen (see the following section).

Using an Exercise Pen for Housetraining

Although a puppy can last in his crate for the night when he’s asleep, you can’t leave a puppy in his crate for purposes of housetraining for longer than four hours at a time during the day. Your puppy will soil his crate, which definitely isn’t a habit you want to establish.

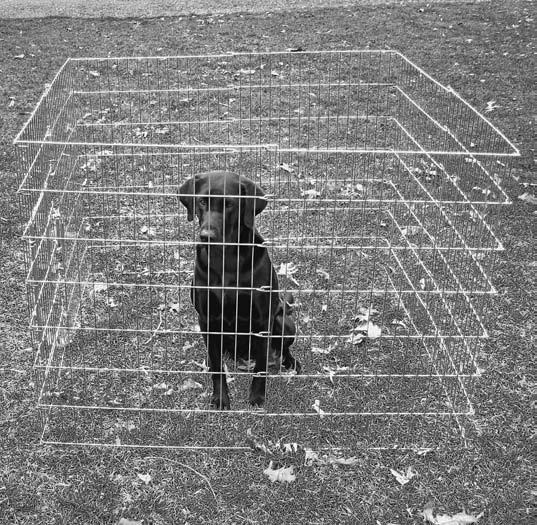

If your schedule is such that you can’t keep an eye on Buddy during the day or come home to let the puppy out in time, the alternative is an exercise pen. An X-pen (see Figure 4-2) is intelligent confinement and uses the same principle as a crate, except it’s bigger and has no top. An X-pen can also be used outdoors. For the super athlete who either climbs over or jumps out of the X-pen, you do have to cover the X-pen.

First, you need to acquire an X-pen commensurate to the size of your dog. For example, for a dog the size of a Labrador, the X-pen needs to be 10 square feet. Set up the X-pen where the puppy will be confined during your absence.

Figure 4-2: An X-pen is another form of containment.

To get your dog comfortable in his X-pen, follow the same procedure as you did in introducing him to his crate (see “Coaxing Buddy into the crate” earlier in this chapter). When Buddy is “at home” in the X-pen and you’re ready to leave him for the day, cover one-third of the area with newspapers for Buddy to use to eliminate on (no, he’s not going to read the sports section). Cover one-third of the remaining area with a blanket, and leave one-third uncovered. The natural desire of your dog is to keep his sleeping area clean.

Remember

Buddy needs to have access to water during the day, so put his water dish on the uncovered area in the corner of the X-pen (some water is bound to splash out, and the uncovered floor is easy to clean). Before you leave, place a couple toys on Buddy’s blanket, put him into X-pen with a dog biscuit, and leave while he’s occupied with the biscuit. Don’t make a big deal out of leaving — simply leave.

Some people try to rig up confinement areas by blocking off parts of a room or basement or whatever. Theoretically, this works, but it does permit Buddy to chew the baseboard, corners of cabinets, or anything else he can get his teeth on. Furthermore, leaving a dog on a concrete surface isn’t a good idea. There’s something about concrete that impedes housetraining; many dogs don’t understand why it can’t be used as a toilet area. Concrete also wreaks havoc on the elbows of large breeds.

You may want to confine your dog to part of a room with baby gates. This option works well for some people and some dogs, but remember it’s no holds barred for whatever items Buddy can access. Lots of chew toys are a must!

Warning!

Whatever barrier you decide to try, don’t use an accordion-type gate — he could stick his head through it and possibly strangle himself.

You’ll find that in the long run, your least expensive option — as is so often the case — is the right way from the start. Don’t be penny-wise and pound-foolish by scrimping on the essentials at the risk of jeopardizing more expensive items. Splurging for an X-pen now will probably save you money on your home improvement budget later down the road.

Managing Marking Behavior

Marking is a way for your dog to leave his calling card by depositing a small amount of urine in a particular spot, marking it as his territory. The frequency with which dogs can accomplish marking never ceases to amaze us. Male dogs invariably prefer vertical surfaces, hence the fire hydrant. Males tend to engage in this behavior with more determination than females.

Doing your doodyBeing a good dog neighbor means not letting Buddy deface the property of others and using only those areas specifically designed for that purpose. Even diehard dog lovers object to other dogs leaving their droppings on their lawn, the streets, and similar unsuitable areas. They also object to having their shrubbery or other vertical objects on their property doused by Buddy. Part of responsible dog ownership is curbing and cleaning up after your dog. Don’t let Buddy become the curse of your neighborhood. Do unto others as you would have them. . . . |

Behaviorists explain that marking is a dog’s way of establishing his territory, and it provides a means to find his way back home. They also claim that dogs are able to tell the rank order, gender, and age — puppy or adult dog — by smelling the urine of another dog.

Those people who take their dogs for regular walks through the neighborhood quickly discover that marking is a ritual, with favorite spots that have to be watered. It’s a way for the dog to maintain his rank in the order of the pack, which consists of all the other dogs in the neighborhood or territory that come across his route.

Adult male dogs lift a leg, as do some females. For the male dog, the object is to leave his calling card higher than the previous calling card. This can lead to some comical results, as when a Dachshund or a Yorkshire Terrier tries to cover the calling card of an Irish Wolfhound or Great Dane. It’s a contest.

Annoying as this behavior can be, it’s perfectly natural and normal. At times, it can also be embarrassing, such as when Buddy lifts his leg on a person’s leg, a not-uncommon occurrence. What he’s trying to communicate here we’ll leave to others to explain.

When this behavior is expressed inside the house, it becomes a problem. Fortunately, this behavior is rare, but it does happen.

Here are the circumstances requiring special vigilance:

– Taking Buddy to a friend’s or relative’s house for a visit, especially if that individual also has a dog or a cat

– When there’s more than one animal in the house — another dog or dogs, or a cat

– When you’ve redecorated the house with new furniture and/or curtains

– When you’ve moved to a new house

Tip

Distract your dog if you see that he’s about to mark in an inappropriate spot. Call his name, and take him to a place where he can eliminate. When you take Buddy to someone else’s home, keep an eye on him. At the slightest sign that he’s even thinking about it, interrupt his thought by clapping your hands and calling him to you. Take him outside and wait until he’s had a chance to relieve himself.

If you catch Buddy in the act in your own house, you already know what to do (see “Identifying the Fundamentals of Housetraining Your Puppy” earlier in the chapter). If this behavior persists, you need to go back to basic housetraining principles, such as the crate or X-pen, until you can trust him again.

Traveling by Car with Buddy

The same rules of housetraining apply when you’re traveling with your dog. In the car, crate Buddy for his and your safety. If he’s still a puppy, be prepared to stop about every two hours. An older dog can last much longer.

Tip

When we travel with one or more of our dogs, we make a point to keep to their feeding schedule and exercising routine as closely as possible. Sticking to customary daily rhythm prevents digestive upsets that can lead to accidents. For a great deal more information on this subject, see Susan McCullough’s Housetraining For Dummies (Wiley).

by Jack and Wendy Volhard